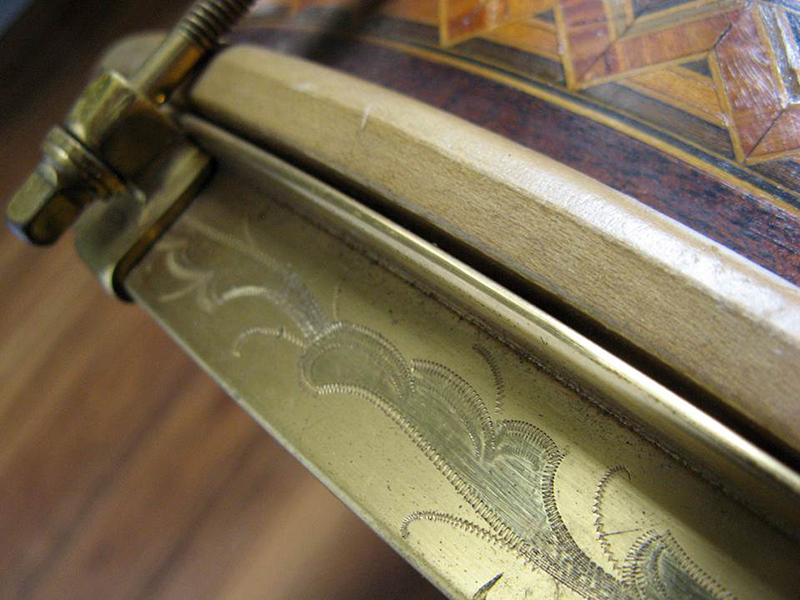

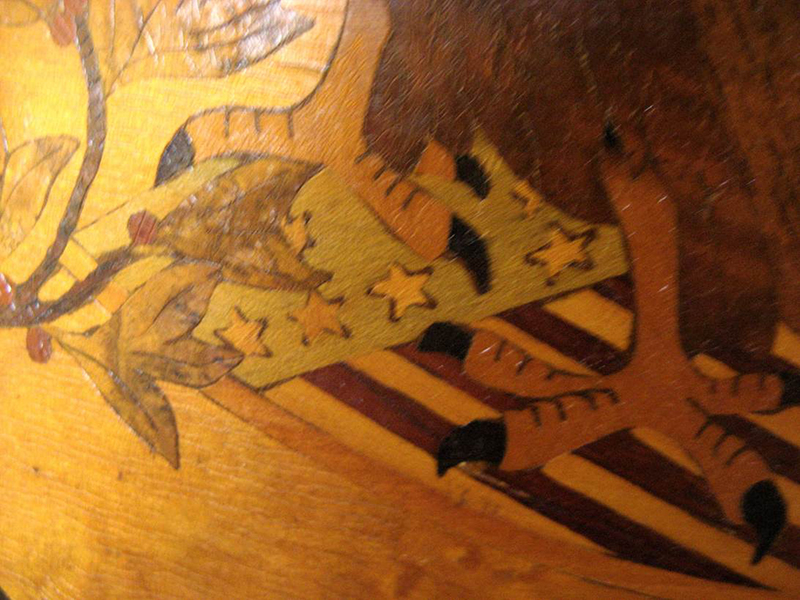

While surfing eBay a few months ago, I came across an auction titled “Rare vintage Buescher marching snare drum.” The drum was 4” X 16” and looked like it had a brass shell. Around the vent hole, there was some nice engraving: “The Buescher, Elkhart, IN” and the serial number, “14157.” It had metal (possibly nickel plated) over wood hoops and what appeared to be the original calfskin heads (the bottom head had “True-Tone, Buescher Band Instruments stamped on it). The tension rods and hooks (8) looked very similar to an early 1920’s Nokes and Nicolai “Double Tension Rod Orchestra Drum” (for pic, click here), where both heads can be tensioned simultaneously by turning the tension rods with a square-slotted wrench, i.e., this requires one side of each lug to be reverse threaded. As such, this would qualify as one of the early free-floating shell designs. The strainer appeared quite different though. It was a bit more primitive, with a dual scalloped tensioning screw attached to the top hoop leading to a trapeze-like, triangular cable snare mounting bar. A leg rest was welded to the bottom hoop. Other than some well-worn heads and a bit of tarnish, the drum looked in rather good shape for being somewhere around 90 years old.

I was amazed that no one was bidding on the drum. This was drum history and needed to be preserved. At least that’s the reason I gave to my wife when I bought it…

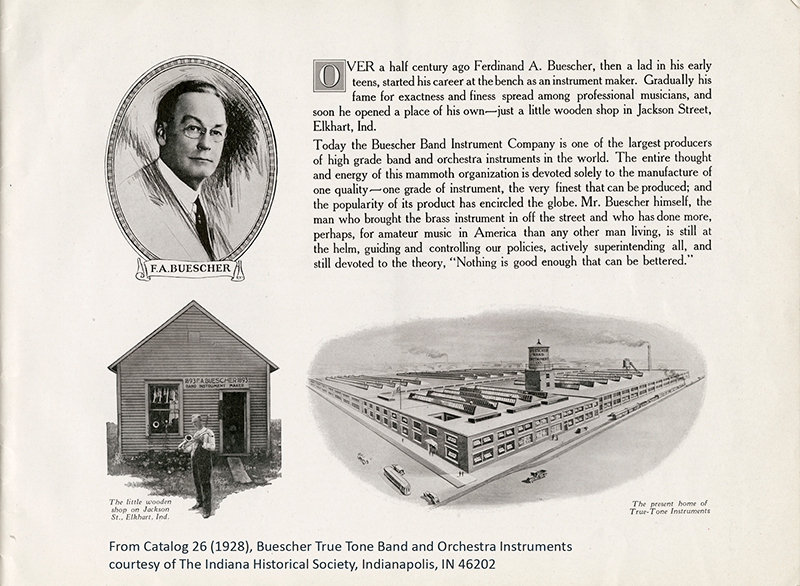

The story behind this drum begins with a man named Ferdinand August “Gus” Buescher (pronounced “Bisher”), born in Ohio on April 26, 1861; two weeks after Confederate forces fired upon Fort Sumter to start the American Civil War. Buescher worked for C. G. Conn in his band instrument factory from 1876-1894, rising to the ranks of foreman but clearly aspiring for something greater. In the fall of 1894, he opened up his own band instrument factory and metal shop on in Elkhart calling it the Buescher Manufacturing Company. In the preface of the Buescher catalogs, it is written: “… Ferdinand A. Buescher then a lad (then a young mechanic) in his early teens, started his career at the bench as an instrument maker. Gradually, his fame for exactness and fitness spread among professional musicians, and soon he opened a place of his own – just a little wooden shop in Jackson Street, Elkhart, Indiana.” Beuscher’s workplace motto was “Nothing is good enough that can be bettered.”

In 1903, there was an unfortunate bank failure that put Buescher in an unfortunate financial position. One year later, he was forced to reorganize the business, restricting it to only producing band instruments, and renamed it the Buescher Band Instrument Company. In 1916 at age 55, Buescher sold a majority stake in his company to six wealthy businessmen. Ten years later, the Buescher Band Instrument Company was absorbed by the Elkhart Band Instrument Company (it is unclear if this was a merger or buyout). Andrew Beardsley, the president of Buescher, and Carl Greenleaf, the president of C. G. Conn, founded the Elkhart Band Company just three years before. Buescher resigned eventually in 1929 but stayed on as a consultant engineer. He died in Elkhart, Indiana on November 29, 1937 at the age of 76. Buescher’s legacy lived on, most notably in form of his TrueTone horns, which are highly collectible and sought after today. Unfortunately, his contributions to our drum heritage were not as well acknowledged, perhaps as they were eclipsed by Conn, Leedy and Ludwig.

One side note: the name Buescher seemed familiar to me but I couldn’t place it at first. George Way leased the Leedy factory building, originally known as the Buescher Building, in 1954 to start production for the George Way Drum Company. In 1963, Buescher was sold to H.A. Selmer, which later became Conn-Selmer, Inc. whose residence remains at 1119 N. Main Street in Elkhart today. So throughout the annals of drum history, the names Buescher, Conn, Leedy, Way and Conn-Selmer (Ludwig) have been connected.

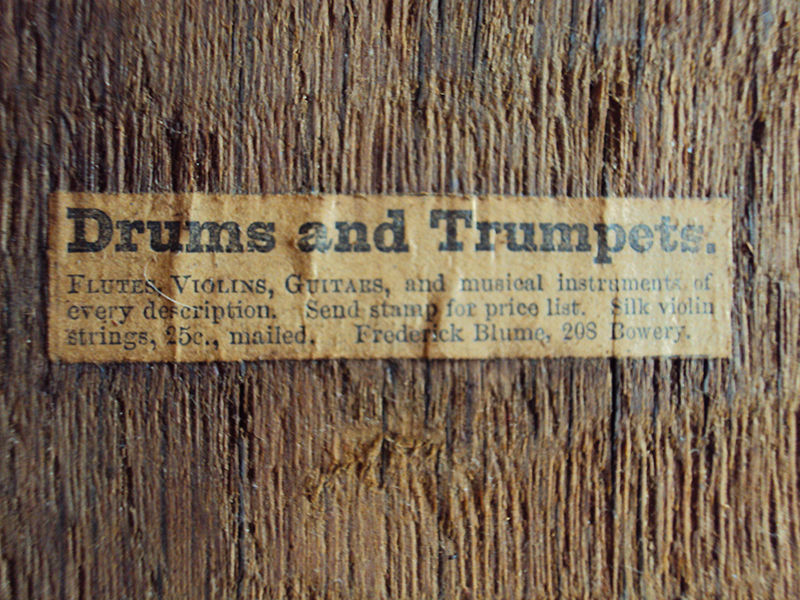

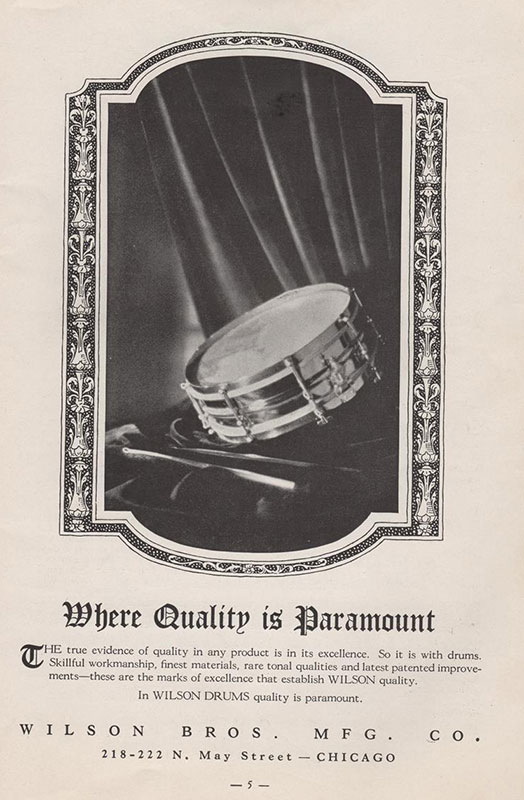

So fast-forward to today and here I am with one of the only examples of a Buescher snare drum that remain. I contacted Harry Cangany and he had not seen one previously. I did my best to find any surviving copies of Beuscher Band Instrument catalogs to identify the drum more specifically. In the 1909 Buescher catalog (see picture), a “#100 True-Tone snare drum for band and orchestra” is shown as being available in either 6” X 16” or 8” X 16” sizes with “two finest calf-skin heads, hoops brass-capped, 16 solid brass tighteners with belt hook, knee rest and 12 waterproof snares.” The options included a “metal shell, highly polished brass” for $15.00.

Now my drum looks extremely similar to the 1909 version, but with subtle differences:

- Only 8 lugs (perhaps the other 8 were removed for convenience? These lugs are not fun to remove…or perhaps a subsequent 8-lug model?),

- 4” shell depth, although it is 6” if you include the hoops,

- Tthe thumb-screw for the strainer pictured appears to have only one scallop, whereas mine has two, and...

- The hoops are not brass capped but seem to be a nickel-plated metal.

According to on-line Buescher serial number guides, the drum (#14157) may have been manufactured between 1911-1912. I located a 1915 TrueTone Drums and Traps catalog at the Indiana Historical Society and found that the Buescher drums had since evolved to either thumb-screw tensioning or center-mounted lugs on the shell. Therefore, it seems plausible that this drum preceded 1915 and was a variant of the close relative pictured in the 1909 catalog. If anyone out there has a Buescher Drums and Traps catalog from 1910-1914, please let me know!

I hope this beautifully engraved Buescher snare drum and short narrative will help you remember Ferdinand Buescher and pass this information down to our next generation of drummers. Until next month, best wishes from this humble student of drum history…