Maker: Increase Blake Dated: 1839 Dimensions: 13.75” (h) x 16” (dia.)

Before the outbreak of the Civil War the largest standing organization of troops in the Union Army was defined by the regiment, which at full strength was usually a bit over 1000 men and officers and comprised of 10 companies. The large scale battles which became distressingly apparent following the battle of First Bull Run/ First Manassas, in July 1861, necessitated the need for larger formations of troops to combat Southern resistance. At this point, the largest of these organizations became defined by the division, which was made up of 2-6 brigades, each comprised of 2-6 regiments. By the beginning of 1862, Union officials had put in motion plans to combine 2-4 divisions into corps formation. In March of 1862, five corps were formed and eventually combined into the Army of the Potomac.

There were four U.S. Army corps designated as the Third (III) Army Corps: Three of which were extremely short lived. These were the Army of Virginia, June-September, 1862; the Army of the Ohio, September-October, 1862; and the Army of the Cumberland, October-November, 1862. Each of these short lived organizations numbered the member corps according to its own existence, a practice that was discontinued as the War moved forward and troop formations became more standardized. The 3rd Corps of the Army of the Potomac was a two year affair and one of fame and glory, as well as the topic of our discussion.

What became the 3rd Corps of the Army of the Potomac, along with four other corps, was formed on March 13, 1862, by authorization of Abraham Lincoln under the direction of General George McClellan. It was immediately ordered to join McClellan’s Peninsular Campaign in Virginia. On the morning of April 30, the Corps had an aggregate of 39,710 (including non-combatants), with 64 pieces of light artillery; 34,633 reported as “present for duty.” However, this aggregate was very short lived due to many issues, not to mention the bullets of the enemy. Amongst the more famous units of the 3rd Corps were the Kearny Division, Hooker’s Division, the Excelsior Brigade, and the Second Jersey Brigade. The Corps found itself in the forefront of many of the battles of the Army of the Potomac, resulting in horrific casualty numbers and ever-lasting fame.

Of the many bragging rights to come from the 3rd Corps, one of the most enduring was the “corps badge.” During the summer of 1862, Major General Phillip Kearny had the officers of his brigade wear red squares of cloth on their hats to distinguish them from other units. The soldiers of the rank and file volunteered to do the same as a matter of unit pride. When Major General Joseph Hooker assumed command of the Army of the Potomac on January 26, 1863, he issued an order for all corps divisions to have colored badges for identification. He assigned Major General Daniel Butterfield, Chief of Staff, to the task of designing a distinctive shape for each corps. Each division of the corps should have a different color of the corps badge for further identification. Since most corps were comprised of three divisions, the colors were red, white, and blue, respectively.

The 3rd Corps of the Army of the Potomac received the diamond as the shape of its badge. As can be seen, this drum has the remnants of a faded, large red diamond painted on the shell, identifying it to the 1st Division, 3rd Corps. This red diamond was obviously added to the drum in the field, most likely by the drummer himself. The red diamond is surrounded by ten white, five pointed stars, which may have been hand painted on the shell at the time the diamond was added to fill out the decoration and draw attention to the distinctive Corps badge.

The adorning façade is flanked on both sides by vertical rows of brass tacks used to reinforce the scarf joint of the 1/8”thick maple shell. The outer lap of the scarf joint was initially held tight by natural glue and a row of small, hand-cut iron nails set intermittingly between the tacks. In the center of it all is a small vent hole that is reinforced by a pewter grommet, indicating the early origins of the drum’s birth.

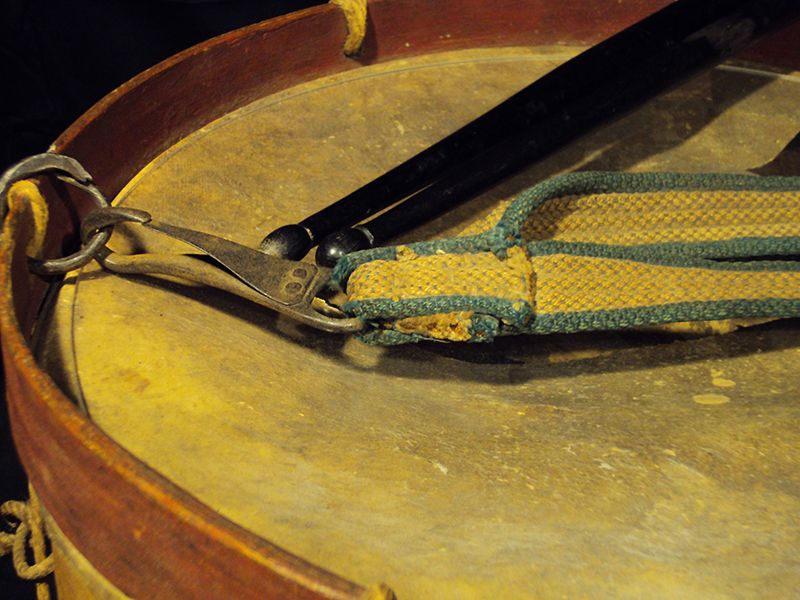

Inside the shell, top and bottom, are two very stout maple “stay” or “glue” rings, measuring 5/16” thick and 3/4” high. Both rings are butt joined and held tight by glue and small hand cut iron nails. The bottom edge of the shell features a rough, hand carved snare bed that works in conjunction with the period, hoop-mounted brass “clam-shell” style snare adjuster.

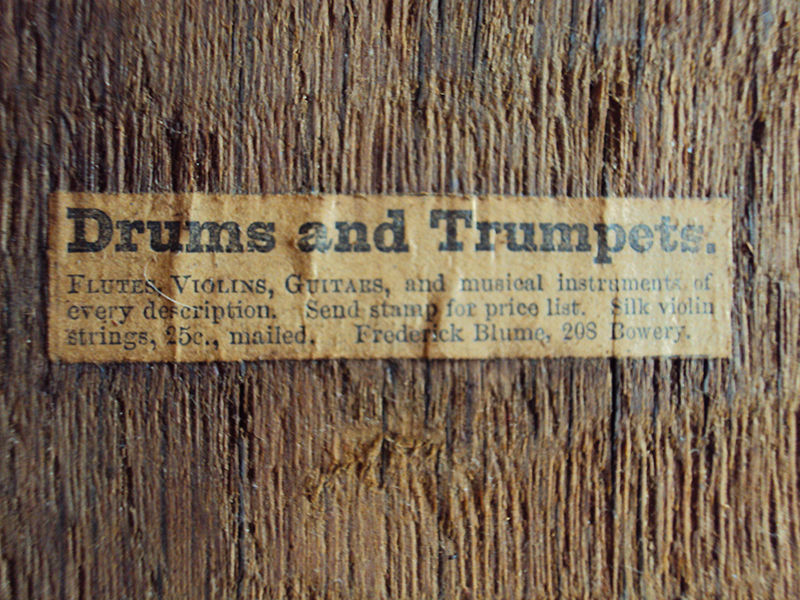

Inside the shell, directly opposite the vent hole is what’s left of the original paper maker’s label indicating the drum was made by Increase Blake, of Farmington Falls, Maine. The label reads: “ St[a]te Drums, / [Man]ufactured B[y] / In[c]rease Blake. / Farmington Falls, Me. / [1]839.” Although legible, this label has seen better days. Increase Blake was known to make drums through the 1840’s in his small shop. Many of his drums were in use by the militia of the day and several were pressed in to service during the Civil War. As a result of the times and his being a small maker of drums, it makes sense to speculate that up to and including the Civil War, the units carrying his drums would be Maine units.

The maple counter hoops were in good shape and measure 5/16” thick and are 3/4” high and painted black. Showing through the black paint is what remains of a former red paint as the hoops may have been repainted at one point or another. Of curious note is that of the ten rope holes in each counter hoop, the pattern of the holes is the most inconsistent of any pattern thus seen. It makes absolutely no sense from a drum making perspective, as can be seen from the final roping. The holes seem to have been drilled helter-skelter with no respect to measuring what-so-ever.

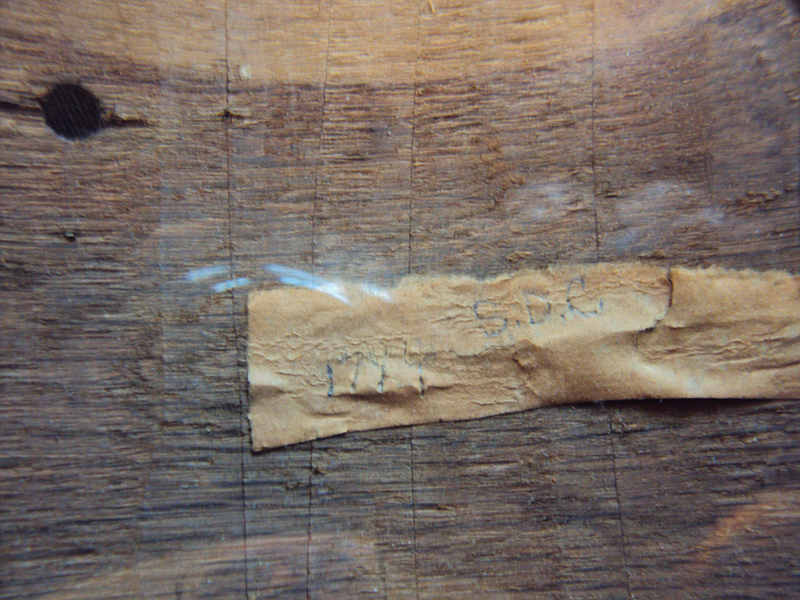

The restoration took a little more thought than most as the temptation to replace the aged and damaged heads had to be considered carefully. The bottom snare skin is covered with partially obscured, painted handwriting that indicates possible names or places, and that the drum once belonged to a drum corps from somewhere in Massachusetts, as well as other illegible and shrouded information. It was decided to preserve the skins until better forensic tools are available to determine the content hidden by the decades.

Roping the drum took more thought than usual, but, came out just fine using period-style linen rope. Four new gut snares, a leather snare butt, and one leather rope washer were also needed. It was decided to use Civil War era rope stays or “ears” as opposed to the square style stays that would normally have been used when the drum was first constructed in 1839. This decision was made as the most important feature of the drum was its use in the 3rd Corps of the Civil War era.

The year 1863 was an extremely destructive period for the 3rd Corps as it was in the very thick of the major operations of the Army of the Potomac. It started the year with over 17,000 men, including non-combatants. In each of the Battles of the Chancellorsville and Gettysburg campaigns, loses surmounted 4200 men. With continuously mounting casualties, expiring enlistments and desertion adding to the mix of depletion, the Corps was drastically being reduced despite new recruits and the addition of a third division. By the beginning of 1864, it was becoming apparent that the attrition eating away at them was curtailing the effectiveness of the organization to operate within the larger Army.

On March 23, 1864, the War Department ordered the discontinuance of the 3rd Corps along with that of the 1st Corps, and the amalgamation of the constituent units of these two corps with the 2nd, 5th, and 6th Corps. The order was very much resented by many of the soldiers of these two units. As a result of much of this resentment, the former troops of the 3rd and 5th Corps were thus permitted to wear their old corps insignias as cap badges.

Only about a half dozen drums with the old corps badges painted on them are known to exist, ranking them very high on the rarity scale. The corps badge became a symbol of extreme pride among the men who proudly displayed them and carried them from the battlefield and on to the many functions, gatherings and reunions of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR). They are also highly prized and sought after by former and current collectors of the genre. This beautiful relic of our American past stands as a constant reminder of the slow death of attrition faced by not only the average citizen soldier in the ranks of the “Late Unpleasantness,” but, by those many brave and noble fellows that chose a drum as their weapon of choice on that of most deadly stages.

From Lancaster County, PA…..Thoughts from the Shop.

Brian Hill