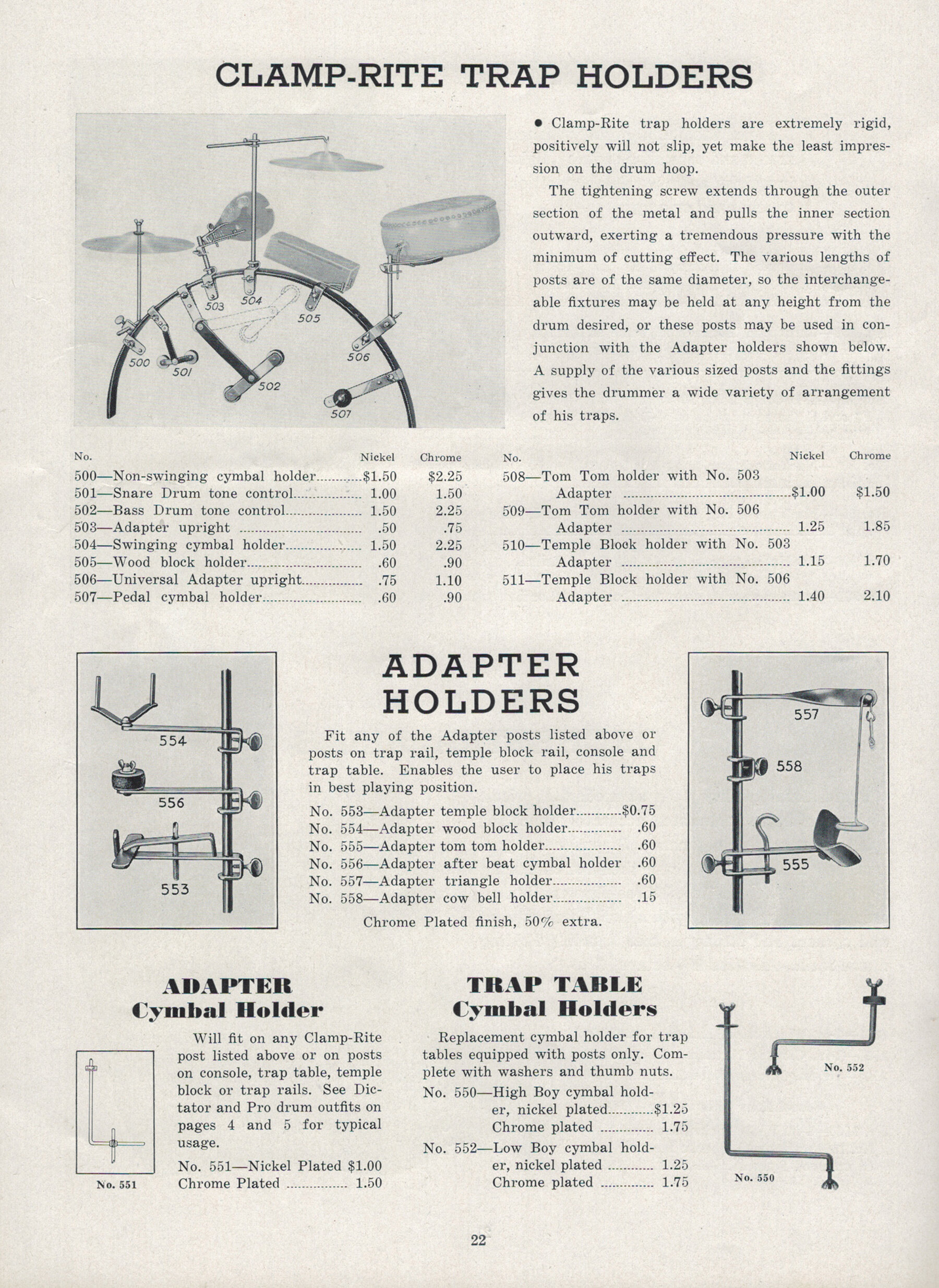

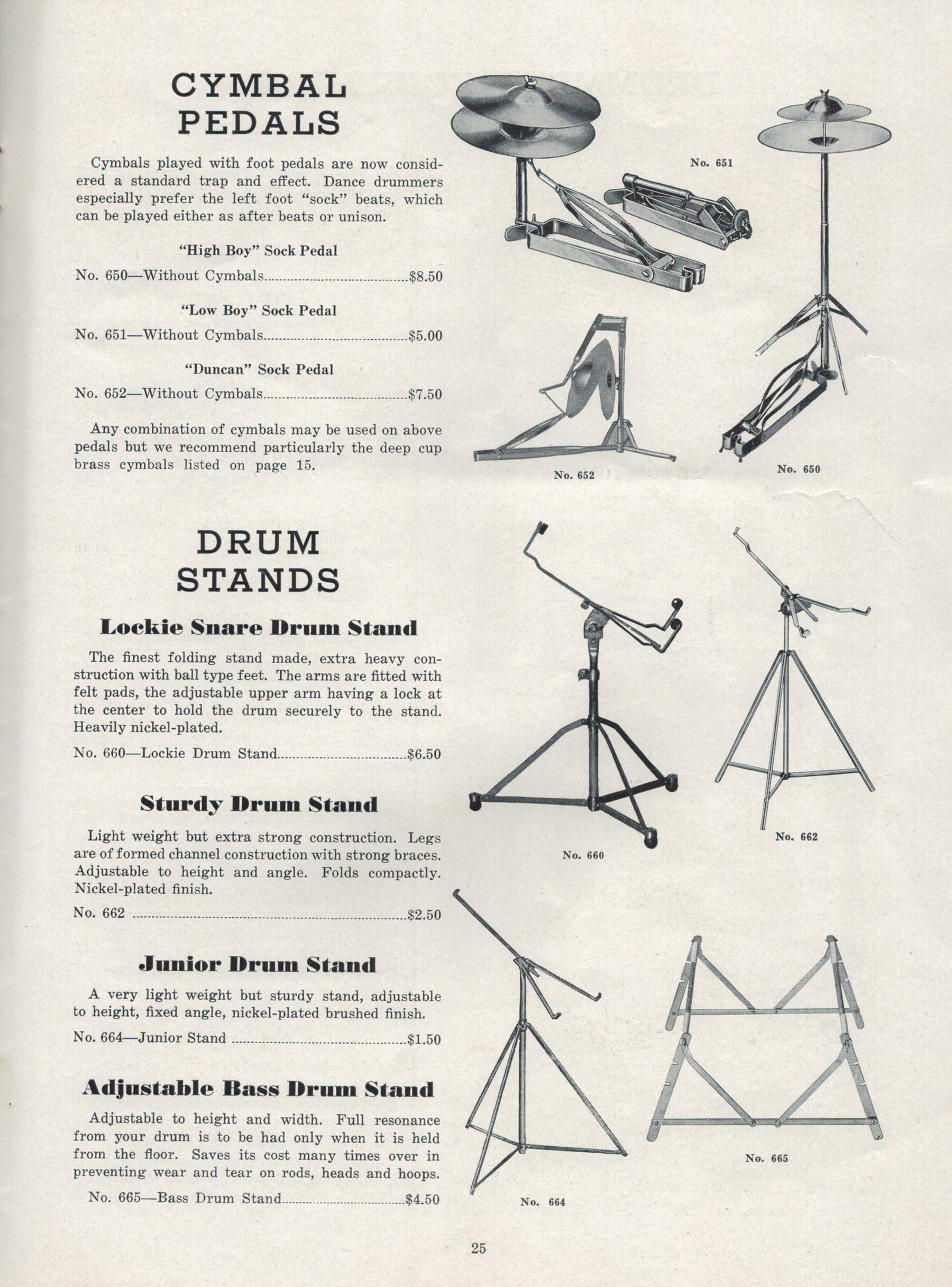

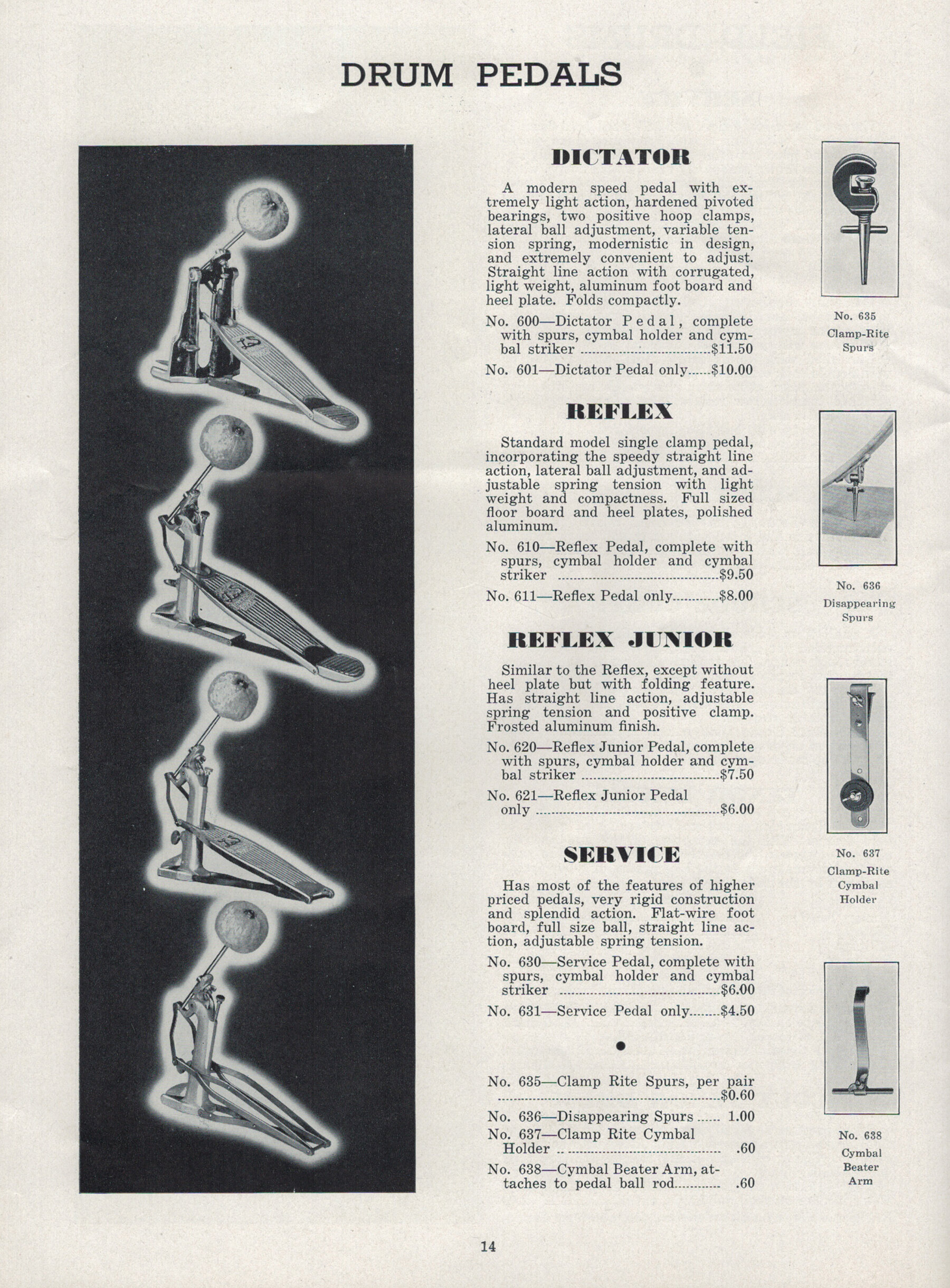

One day in late 2020, I was doing my usual browsing through vintage drum-related social media posts and came across a 1936 Leedy & Strupe (L&S) white marine pearl drum kit for sale. This L&S kit consisted of a white marine pearl 14 x 28” bass drum (with calf heads), 9 x 13” tom (tacked bottom head), 6.5 X 14” snare, cowbell, and various hardware (original L&S bass drum pedal, hi-hat with lamb wool beater, Clamp-Rite trap holders, spurs). According to Harry Cangany (noted author, drum historian), this kit was, “a ‘Dictator’ model in white pearl (L&S name for white marine pearl)…1936 is probably correct.”

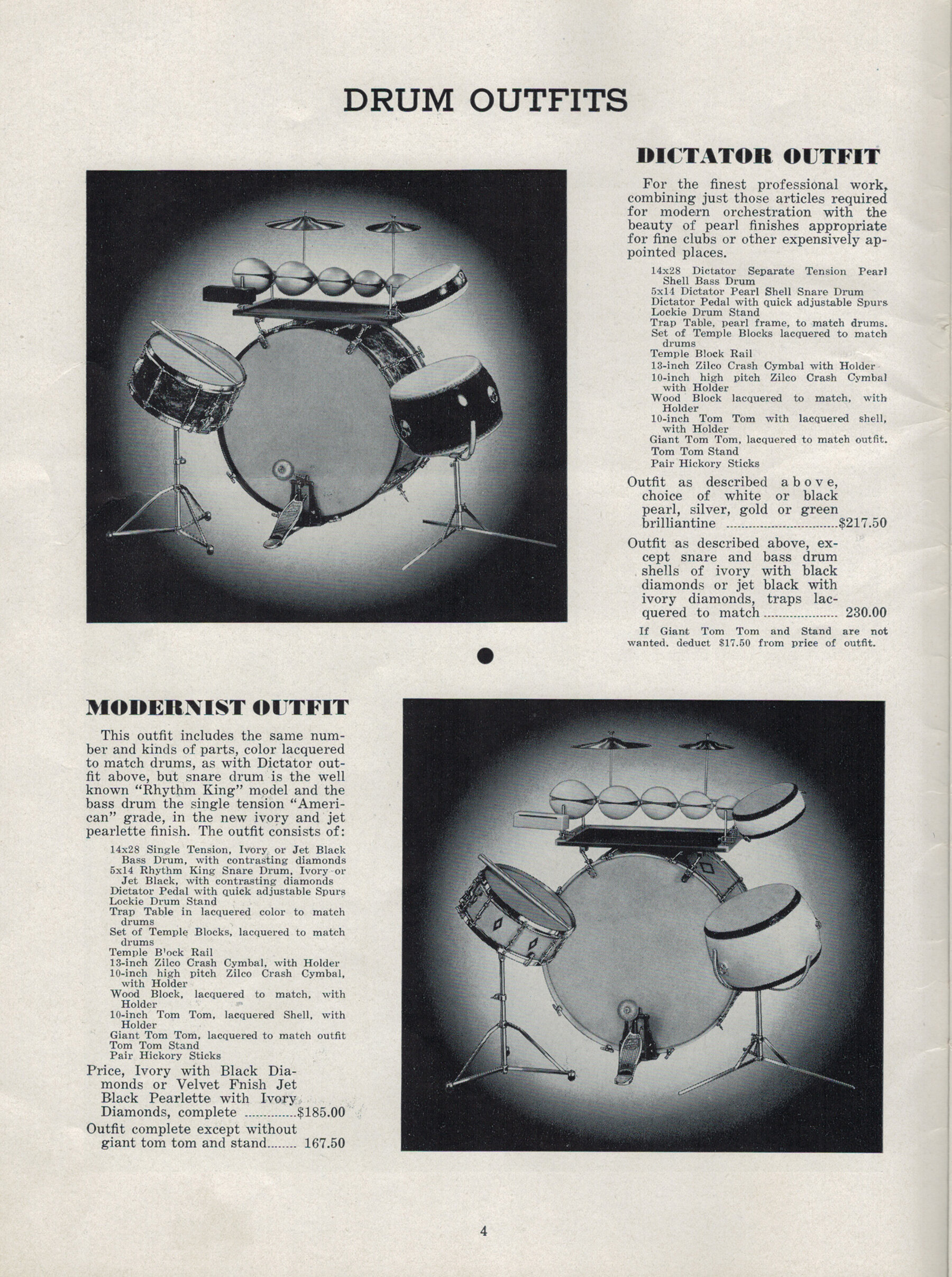

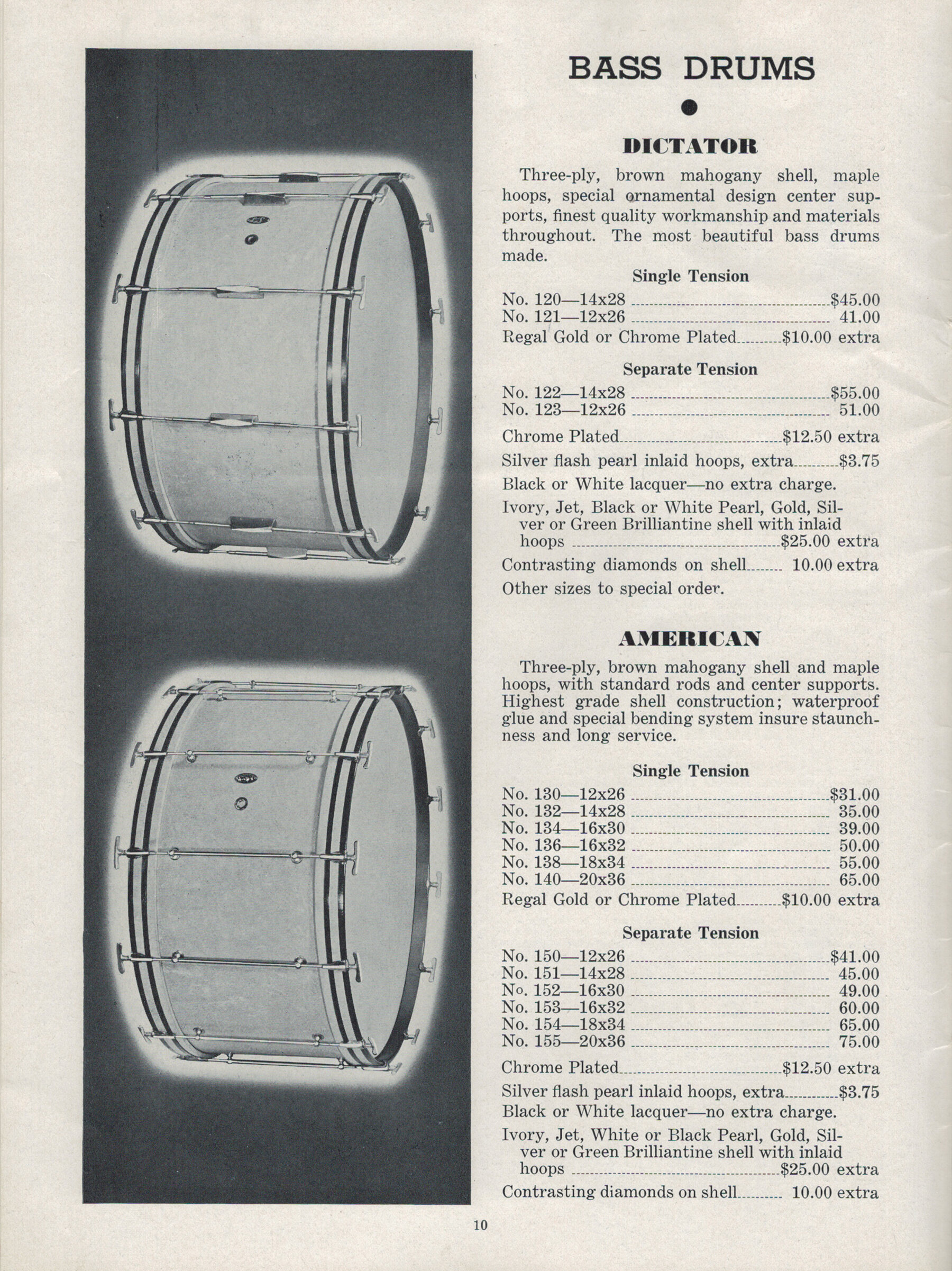

I am fortunate to have an original copy of the 1936 L&S catalog in my collection. According to the catalog, the Dictator Outfit was designed, “For the finest professional work, combining just those articles required for modern orchestration with the beauty of pearl finishes appropriate for fine clubs or other expensively appointed places.” At $217.50 in 1936, this kit was not a small investment.

The Dictator outfit and snare in the 1936 catalog differed slightly in that it showed an oval L&S badge while this kit had circular badges. I asked Harry about this and he responded, “The little oval badge was first, and there was an oval Strupe badge, too. As far as I know, there were 2 catalogs and a flyer. They all show the oval badges. My guess is that the photography was done (used in all of them) just as the company was getting started. Leedy Indianapolis didn’t use badges until the last runs in 1930. I have seen one round Leedy Indianapolis badge in all the years of looking at Leedy drums. So, I think L&S followed the Leedy model—no badge on an air vent. But everybody else used logo badges and I think they probably started using them to look modern. Can’t be sure when. In the 1936 catalog, there are no tom toms and the set you bought had one, so perhaps your L&S set is near the end of the company’s time in Indianapolis. Can’t be sure because catalogs never tell the whole story!”

In one of our chats, I asked the owner, Mike, what he knew about the history of this L&S drum kit. Mike indicated that he had a dear family friend, Steve Chapman, from Vernon Hills, Illinois. About 11 years ago, Mike had a chance to speak with Steve’s father, David E. Chapman: “I happened to be over my friend’s house, and his Dad was there. We just happened to get talking about drums. Until then, I didn’t know he was a drummer. He then showed me an old drum kit that had been sitting in a closet for 40 plus years. I was intrigued by the calf heads and unusual snare. From our conversation, I could tell he was a jazz player. We talked a lot about that. Some years later, David realized that he was in ill health and wanted to pass the drums on. He contacted me and asked if I was interested. Of course, I said yes. I got invited to his house for dinner and essentially got interviewed to see if I was the right guy, a player and a serious custodian, for this kit. Luckily, I was the right guy, and he sold me the kit.” Unfortunately, David Chapman died within a year of selling it to him. According to the stories Mike heard, David traveled widely playing jazz and swing, one-time as a back-up for Charlie Barnet’s drummer. Note: I could not find any written or online documents on David E. Chapman to verify this info.

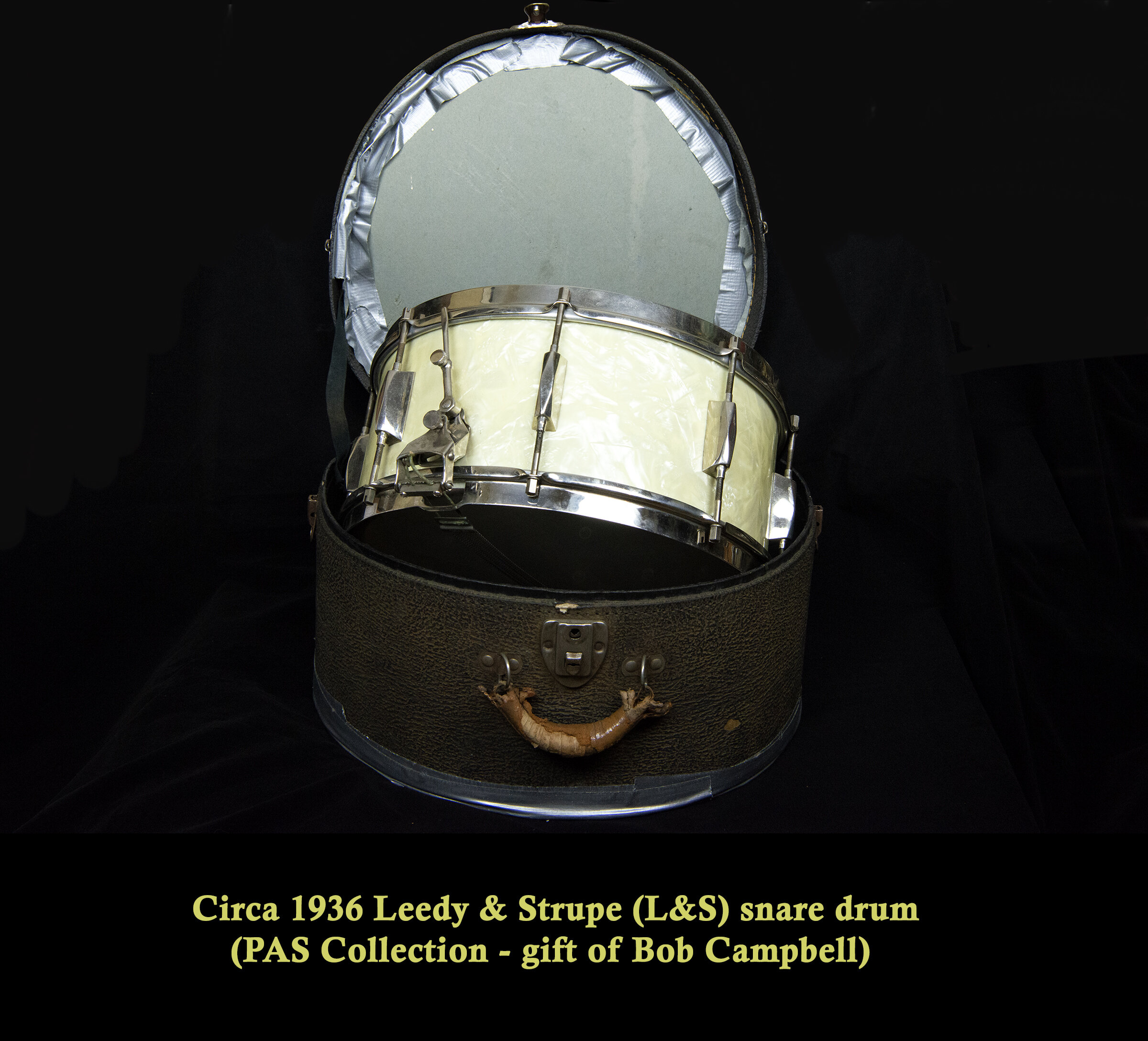

As a matter of practicality, I am a snare drum collector and do not generally buy kits. The snare drum was in really excellent condition and quite a rare model. I admittedly first approached the owner, Michael Gorsuch, about just selling the snare. We had a number of conversations by phone and text. It became quite clear that Mike wanted to keep the kit together and in the hands of someone who would appreciate its historical significance. I was certainly very interested in getting some hands-on experience with the snare but greatly respected the need to keep the kit together.

After some thought, I came up with a proposal. I would buy the entire kit, hang on to the snare to play for a short while, and then donate all to PAS here in Indianapolis (I live in a northern suburb of Indy). In this way, the kit would be well-cared for and available to other drummers via the Rhythm! Discovery Center. Mike really liked this idea, so I contacted Joshua Simonds, Executive Director at PAS. I asked him if he was interested in adding a 1936 L&S kit to the R!DC collection. Joshua’s response was, “This is wonderful, and it would be a great donation to have with a nice Indianapolis connection as well…Thank you for always thinking of us.”

So just before Christmas, Mike drove to my house and kindly dropped off the kit (wearing masks due to COVID!). While there certainly was some wear and tear (not surprising for an 84-year old instrument), it was really an amazing piece of drum history to behold. The calf heads sounded so warm, and the bass drum felt huge in both size and sound. The L&S bass drum pedal and hi-hat were in great shape. I loved their simple and collapsible design. A few hours later, Elizabeth Quay, R!DC Museum Manager & Registrar, picked up the kit (minus the snare), thus ending my delightful encounter with this L&S marvel of drum construction.

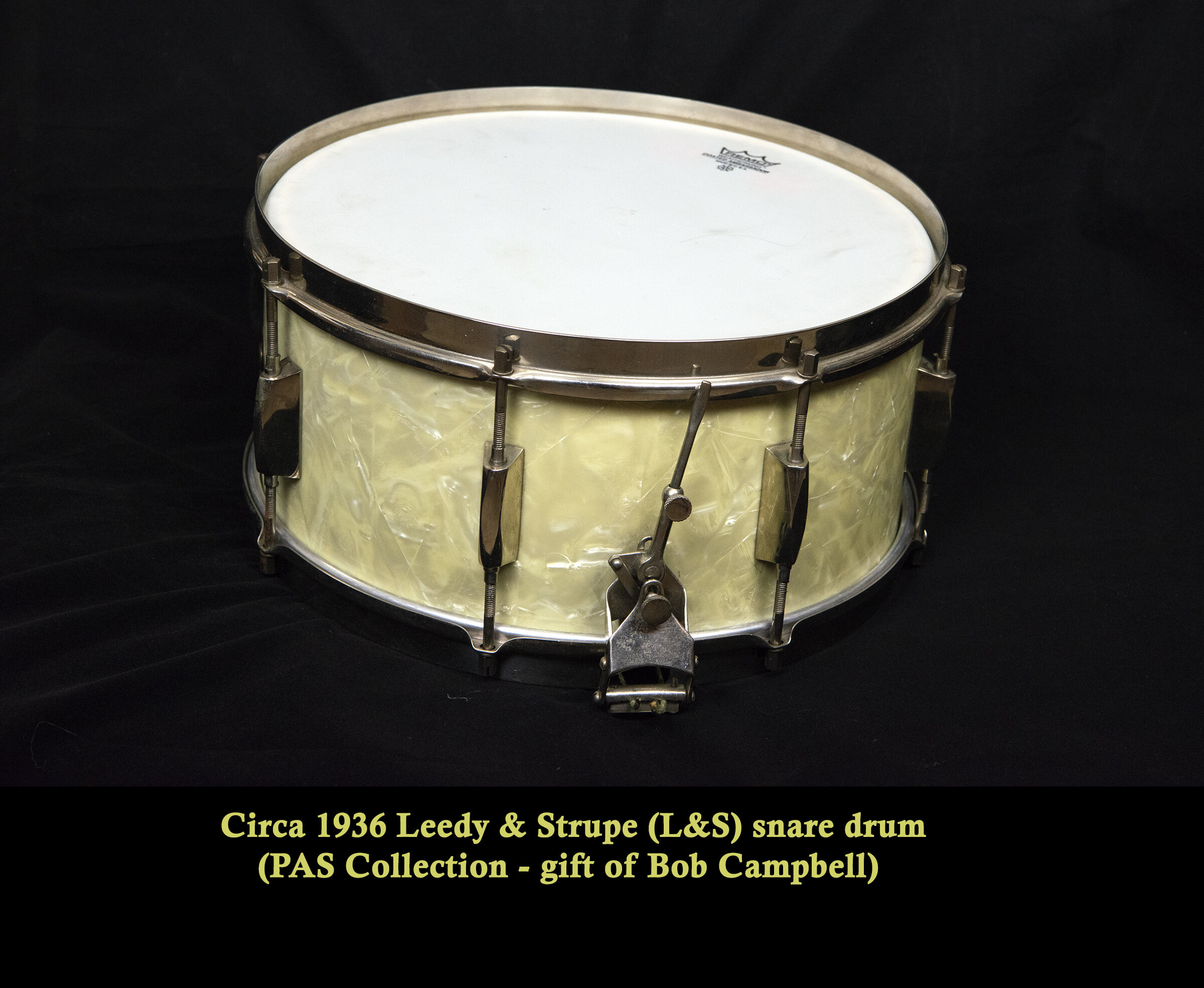

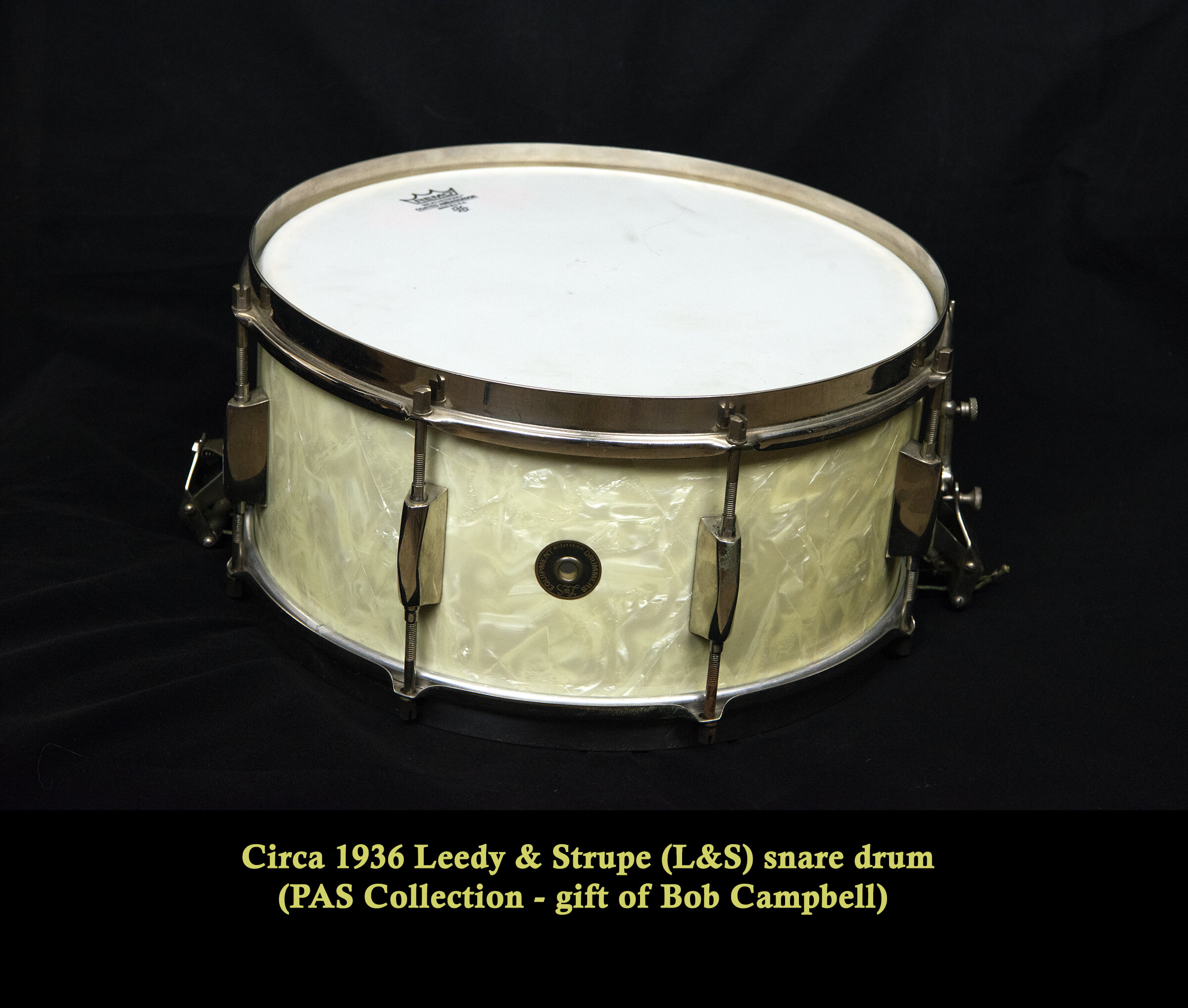

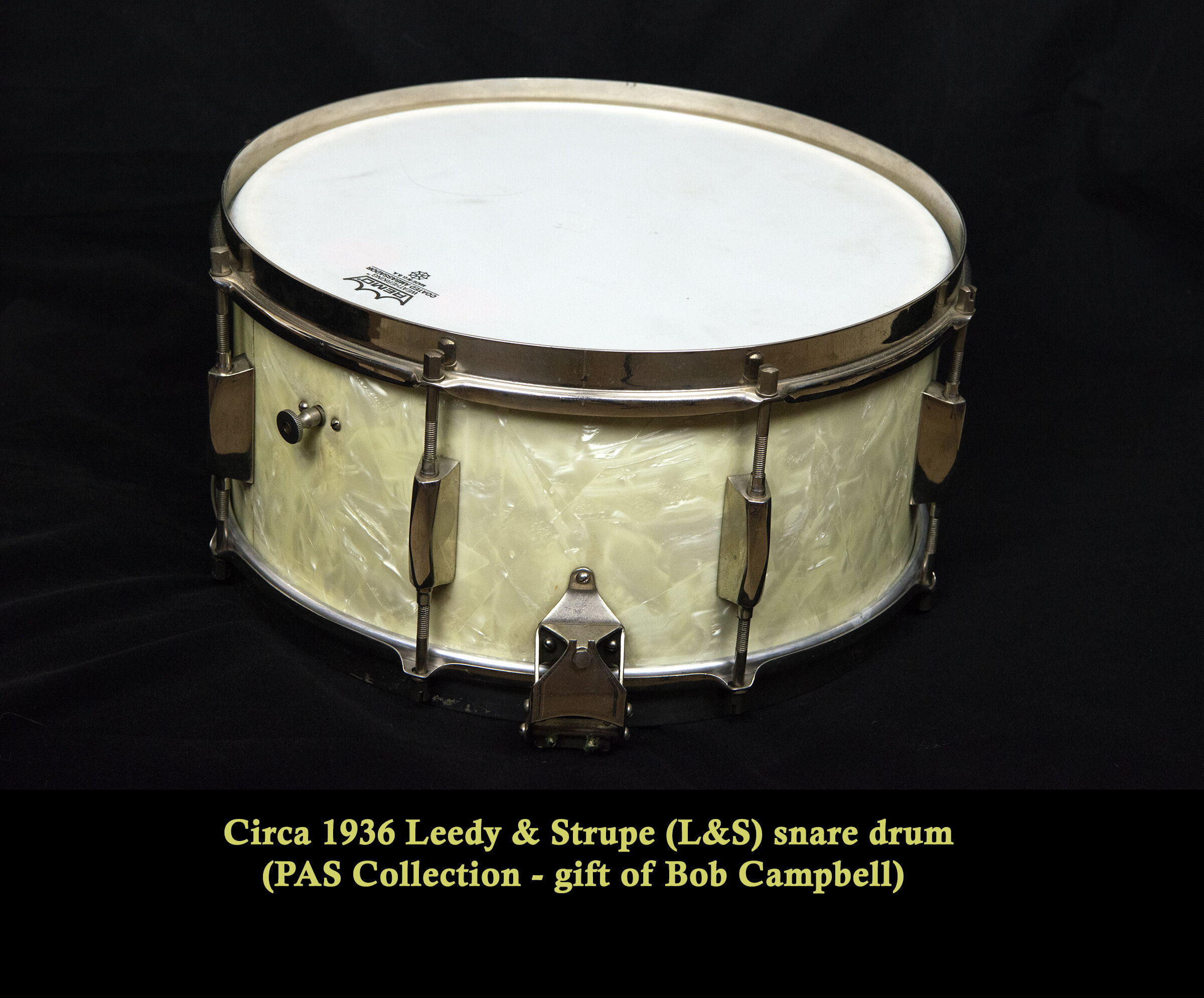

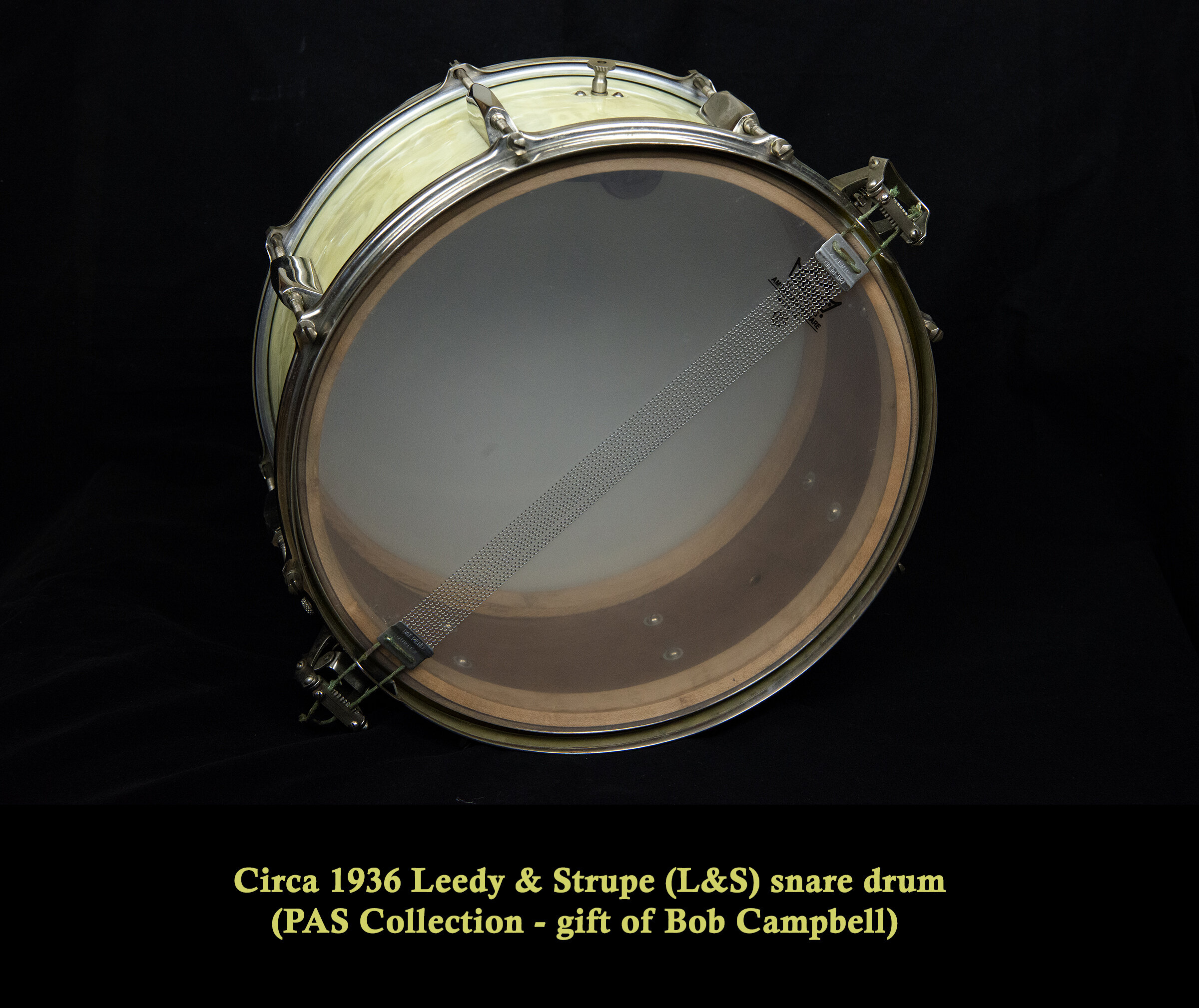

The snare close up looked just as good as the pictures, with very little fade in the wrap and minimal pitting. It had 8 slotted tension rods with classic L&S beveled lugs (similar to Ludwig Imperial lugs but with a “softer” profile), 12-strand Duplex snare wires, and double-flange hoops that were very reminiscent of the earlier Leedy drums. The dual plane strainer had a paddle-like throw-off arm (like those used in early Leedy) but very unique in design relative to earlier Ludwig or Leedy strainers. In the 1936 L&S catalog, the Dictator De Luxe grade snare drum was offered in 5 x 14”, 6 ½ x 14” and 6 ½ x 15” sizes. According to Harry Cangany, this was a mahogany shell. Finishes were “pearl in white, ivory, green or black, or with silver or gold brilliantine.” The Dictator snares were offered with nickel-plated hardware, although chrome was offered as an option.

I did get a chance to play the snare a bit - it was truly delightful. The Dictator snare was warm but articulate, with a great dynamic range and sensitivity (no choking although I was relatively cautious in not hitting those vintage hoops too hard). I would have preferred 20-strand wires for a little more snare buzz, but that is my personal preference from a contemporary perspective. Overall, it was an amazing and almost existential experience to play this drum thinking that it sounded the same to a drummer 84 years ago. I hated to give it up, but off it goes to the Rhythm! Discovery Center for future generations of drummers to appreciate.

Many thanks to Michael Gorsuch, Harry Cangany, Joshua Simonds, and Elizabeth Quay for their help and support with this article and facilitating the donation. I strongly encourage others to consider donating to PAS and the Rhythm! Discovery Center in support of the preservation of our drum heritage.

http://www.RhythmDiscoveryCenter.org/

For more info on Leedy & Strupe, please check out the following links/references:

https://www.notsomoderndrummer.com/not-so-modern-drummer/columns/harry-cangany-catalog-corner/1936-ls-catalog-leedy-strupe (Harry Cangany, NSMD, 2013)

An excerpt: “In October, 1929, an ailing U.G. Leedy sold Leedy Manufacturing to band instrument giant C.G. Conn Ltd. For the next 9 months, Leedy drum building was in a state of transition. In August of 1930, the Elkhart factory was up and running. In those intervening months, Conn sent in a supervisor, Ed Cortas, and many employees came and went. Leedy himself hoped that his 100 loyal employees would have jobs in Elkhart, but many of them did not or could not or, more probably would not, move.

U.G. decided to create another company called General Products. Concerned that the Depression would not bring in drum sales, Leedy wanted General Products to make other products as well. But, they would make drums. The legend has become fact. He wanted to name the company Leedy & Sons. He had two sons—Eugene and Edwin, later called Hollis. Conn had just spent $900,000 in cash to buy the Leedy name, so there could be no use of that name outside the drums now made by Conn.

Mr. Leedy bought a former dairy building and started the process of turning it into a drum factory. Some of it was completed when he died in January, 1931. His widow gave this fledgling company the funds to complete the woodworking shop. Edwin joined as Secretary Treasurer. Eugene did not become involved.

Leedy and Sons became L&S, and we now think that L&S also stood for Leedy & Strupe. One of the former key Leedy employees who did not leave Indianapolis, at that point, was Cecil Strupe, the engineer. He was named president of L&S. In the earliest days of production, there were also Strupe badged drums. It may have been an attempt to circumvent the Leedy name while promoting Strupe’s name since he was known to drummers thanks to frequent mention in the Leedy Topics.”

Post-script: “He (Ed) absolutely hated Strupe. Ed left the company and went to work in Indianapolis for Curtis Wright, maker of propellers for planes. They were in the old Marmon plant on the Southside. L&S was sold. The ready-made drums were bought by Indiana Music (Rinne family) and the "company" was sold to Sears, and they made drums that looked like L&S until World War II. Strupe went to Chicago and joined WFL and he gave us the triple flanged hoop while there.”

See also:

Harry Cangany, “The Great American Drums and the Companies that Made Them 1920-1969”, p. 26-27, Modern Drummer Publications, Inc, 1996.

Rob Cook, “The Leedy Way”, p. 178-183, Rebeats Publications, 2018.