(editor’s note: I’d like to thank Bob Campbell for this extremely in depth article about John Aldridge’s career in drum engraving. John founded Not So Modern Drummer in 1988 as a result of his passion for engraved Black Beauties and his single minded pursuit of saving and mastering the art of drum engraving. His passion and dedication to vintage drum history is contagious. I consider his efforts to be the most important factor in establishing the vintage and custom drum community in the latter part of the 20th century. Telling this tale has been long overdue and is one of the most, if not THE MOST, important articles ever published in Not So Modern Drummer).

Like many drum collectors, I have always been fascinated by the engraving on old 1920s-30s Leedy Elites, Duplex Black Jewels, and Slingerland and Ludwig Black Beauties. The work was all done painstakingly by hand with wonderful detail. These engraved drums were limited in number and fetched a premium price. However, if you look very closely, the engraving is certainly not flawless. Perhaps analogous to a drum machine being “too perfect”, machine-engraved shells do not seem to have the same allure or beauty of the hand-engraved drums. The beauty is in the uniqueness of each personalized drum, flaws or variations included. This is the esthetic art of our craft. It is literally how the drum engravers have made their mark(s) over time.

Workmanship in drum construction has been given a lot of attention, but quite little has been said about the embellishment that comes in the form of engraving. I have often wondered what it would be like to interview these early engravers. Who came up with the patterns? How did they learn to do this? Were they drummers? How many engravers were there? The engravers of the 1920s-30s are long gone with no detailed record of their existence. It seems a shame that their story was never captured and shared. I hope to correct some of this injustice by sharing the stories of our modern drum engravers. In this way, their stories will be passed on to future generations. The first of these is the best-known drum engraver of our time, John Aldridge. Some years ago, John Aldridge wanted a hand engraved drum. When he discovered he couldn't afford it, John learned how to do it himself, and brought this lost art form back to the drum industry. John is a well-known authority on vintage drums, having published the “Guide to Vintage Drums” (1994) and as the founder/publisher of Not So Modern Drummer magazine from 1988-2007. John has contributed to other publications such as Paul Schmidt’s “History of the Ludwig Drum Company” (1991) and appeared in Daniel Glass’ superb DVD documentaries on the history of the drum set from 1865-1965, entitled “The Century Project” and “Traps: The Incredible Story of Vintage drums” (2012). You'll also find his credits as an editor or contributor in just about every book on the topic of vintage drums written since 1989. Since 2005, John has been the drum technician for Brian Hitt of REO Speedwagon. In his luxurious free time, John engraves drums. John kindly spoke with me recently about his personal experiences with vintage drums and engraving.

NSMD: Can you tell us a little about your background that led up to your becoming a drum engraver?

“After I discovered the differences in the various eras of Ludwig Supraphonic, my interest in vintage drums grew. I started looking for other vintage drums around Tulsa. In my search, I ran across a vintage clothing store called ‘Global Village’ with a hand painted sign in the window advertising ‘Vintage Drums in back’. I went around the back and into a dusty, recently flooded basement where a lot of old drums were piled up. The proprietor Bob (who has since closed the store and wishes to remain anonymous) was an enthusiastic collector of all things vintage, but especially drums. That day was the first day I ever saw an engraved black beauty up close and in person. Bob expanded my network of collectors and introduced me to a several people across the country who were buying, selling and trading vintage drums. I’ve been a drum collector for a long time, since about 1983. I got really involved in it. There weren’t a whole lot of people collecting vintage drums at the time. I met Jim Pettit (Owner, Memphis Drum Shop) and Greg Wilson, who were drum collecting fools from way back. They were both Ludwig Black Beauty fanatics and each of them had a half dozen or so in the early 1980’s. They introduced me to other collectors, and the first vintage drum dealer I ever met, Charlie Donnelly (who passed way in 2007). When I started Not So Modern Drummer in 1988, I only knew 32 people who were into vintage drums! That’s also around the time I met Harry Cangany.In the late 1980's, I was teaching Elementary Music at Macintosh Elementary in Chelsea, Oklahoma, teaching private percussion at night at Rogers State College, and performing with the Sammy Pagna Big Band and all its subsidiary ensembles. All my discretionary funds came from buying drums, fixing them up for students, and refurbishing things I bought from pawn shops. That’s how I started to pick up information about vintage drums. I loved the sound of the nickel over brass Ludwigs from the 1920’s. Once I saw a Ludwig Black Beauty, I knew I had to have one. But the $600 price tag (!) was way out of my reach at that point. In my infinite wisdom, I thought I’d find an engraver and get him to engrave my plain 1920’s Ludwig Standard. I went all over the Tulsa area looking for an engraver and finally found one at a jewelry store in a mall. He said, ‘Bring me a picture of the drum and I’ll give you a quote.’ I brought him the picture and he gave me a quote alright… $750! That was around 1984. I said, ‘Wow’, and told him that was more than the Black Beauty I was trying to duplicate. He said, ‘Well, it’s a tedious process, and not too many people do it anymore. I’d have to bone up on a set of tools I don’t generally use.’ So that turned me off to that idea.

Sometime later, I was in a jewelry store with my wife. I happened to look up on the top shelves and noticed a lot of ornately engraved silver platters. I said to the jeweler, ‘Who did all the engraving? That stuff is just beautiful.’ He said, ‘Oh, that’s my Dad.’ Sitting at a workbench, repairing a watch, was this little old man looking through a jeweler’s loupe engraving his initials inside the watch to show he had done the work. You’d need a microscope to read his initials and he was doing it just with a loupe! I asked him if he would consider engraving something for me. He said, ‘Nope, I’m retired from engraving.’ His son added, “All Dad does these days is go to pet shows and engrave the trophies. That’s it.” I hung around this place and bugged him long enough to get him distracted. Finally, he asked me what I wanted to do, and why I was so obsessed with engraving. I showed him a picture of the engraved 1920’s Black Beauty I carried around in my pocket. He said, ‘Son, that’s pretty easy. It’s just three strokes.’ He then showed me the tools needed (called gravers) and demonstrated on a flat piece of metal how to cut an upward loop and downward loop, and how to slide the blade sideways as you’re cutting forwards. That took about ten minutes and was all the "formal" training I ever got. Gravers come in a lot of different shapes and sizes. I use a type of graver called a Flat Graver; it has a square tip. The sharp edge then has two tips, one on the left and one on the right. You’re walking the blade from tip-to-tip in an arcing stroke, digging out the metal in between the tips. That zig-zag movement is called ‘wriggling’.” It’s a simple craft. You can carry everything you need to engrave in your shirt pocket. . . but I don't recommend it.”

NSMD: What is your general technique for tracing a pattern on the drum shell?

“In the beginning, I used to draw the patterns directly on the shells. That was when I was doing just 1-2 at a time. It took about twice as much time to draw the pattern as it took to engrave it. That wasn’t working out well when I had a lot of drums to engrave. Then computers caught up to the point where you could draw Bezier curves. Now when I draw a pattern, I draw it on paper. I’m not a really good artist. I draw a shape, scan it and put it on the computer. I use encapsulated postscript (EPS) which enables me to draw Bezier curves. I can adjust it perfectly to make it look better than my drawing. Once I have the pattern drawn with simple lines, then I replicate the parts and flip them upside down and sideways for where I need them. All four of these patterns are just one pattern that’s been treated to look mirrored and flipped over. This keeps them all symmetrical. I then print the pattern out on paper. I cut it into strips so it will straddle the bead of the shell (one strip on the top; one strip on the bottom). I mark the lug holes on the pattern. When I put a pattern on the drum, I just poke a pencil through the hole to position the pattern. Then I tape it on there and take a piece of white carbon paper and tuck it underneath the other paper (with the pattern). I draw over the pattern on the paper, and the white carbon paper transfers that to the shell. When I remove the pattern, it leaves a white drawing on the shell. I have a stockpile of all the patterns I’ve used throughout the years. Whenever somebody wants a certain pattern, I go through my stock and fish up the closest thing and resize it on the computer to fit the space on that size drum. That way, I don’t have to redraw the pattern completely. I also keep a digital archive of the patterns that I do a lot. It's come in handy to mock up a pattern for a customer.

When I first started engraving, I ran into a horn salesman and collector at a music store and asked him how they applied the engraving patterns on trumpets and saxophones. He said they used a ‘pounce’ pattern. I had no idea what that was. He explained that they took a piece of aluminum (or tin) foil and draw the pattern on it. Then they take a wheel that has teeth on it and rolled the wheel over the pattern, cutting little holes in the lines of the pattern. Then they laid that piece of foil over where they want to put the pattern and took a bag of rosin and shake it over the foil. The rosin dust fell through the holes in the pattern, sticking to the metal underneath. When they peeled off the foil, there was a pattern of dots.

Another method of applying patterns is to use Chinese White watercolor. You can buy it in tubes or blocks. I have a little piece of it that sits on my workbench. Whenever I want to do one panel where I’m going to draw a name or stuff like that, I lick my finger, rub the white block and paint that spot on the shell with white. It dries, and I draw on it with a pencil. If I’m going to do a custom drum that has a lot of individual stuff on it, every spot that has something special like a name or initial, I draw on the shell mostly freehand. I’ll paint it white, draw it on with a pencil and cut it out, then rinse off the white.”

NSMD: How do you feel about engraving vintage drums, drums from the 20s-40s that weren’t originally engraved?

“I don’t mind cutting into a vintage drum that’s got a lot of wear, but I don’t like engraving a cool old drum that’s otherwise perfect or near it. I figure it has survived this long without being tattooed. You have to leave a few to remember in their natural state!”

NSMD: Why don’t more people do drum engraving?

“Because it’s tedious, boring, and takes a long, long, long time to get any good at it. Unless you’re a naturally gifted artist – which I’m not. An artist would probably get the hang of it a lot quicker than I did. I had to learn the art part of it along with the physics of how to move the blade. There’s no book on wriggle engraving. I bought every book I could find on engraving, like James B. Meek’s ‘The Art of Engraving: A Book of Instructions’. He talked about wriggling but didn’t describe how exactly to do it. I tried to call him when I got the book, only to discover he died the year before! Since then, all of the engravers in the business that I talked to use pneumatically assisted gravers that push the blade through the metal instead of using wriggle style to lever the metal out of the way. It looks like the same tool that I use, but inside the hand piece is a pneumatic hammer. Coming out of the back part of the handle is a pneumatic tube that goes to a controller or a unit on your workbench. There’s a foot pedal that controls the speed of the pneumatic hammer in the handpick. You put the point on the drum, push down on the foot pedal and steer the blade. I don’t do it that way because I consider it cheating (laughs). It’s not like the engraving on most vintage drums. I wanted to engrave to do one thing – and that’s drums. I wanted to do it in the style of the drums that I liked, which was used by Ludwig, Leedy, Slingerland, etc. You can use the Gravermeister and make something that looks beautiful that used to take months to accomplish before the machine appeared, but the lines will not look like the wriggle strokes used on the vintage drums that inspired me to engrave.”

NSMD: So how long did it take you to master your skill?

“I’d say in another ten years; I’ll have it mastered (laugh). I’m a good engraver now, but I look at the work that Adrian (Kirchler) does and it just makes me want to go cry in my beer! Adrian is a very talented and trained engraver. He is a real go-getter. The first time I met him was at the Amsterdam Drum Show in 2004. He walked up and apologized to me. I said, ‘Why are you apologizing?’ Adrian said, ‘Well, I’m copying your work and engraving drums.’ I said, ‘It’s a pretty big planet. I reckon it’ll be OK if we just split her down the middle.’ He laughed, and we got along just great. The next thing I saw was that he was working with Johnny Craviotto. I might have been upset if I hadn't already been tied up doing a limited edition for Ludwig. It's surprising to see that several people have started engraving drums in the U.S.A. in the past few years.

I started out when I was a school teacher. At the time, I wasn’t playing that much. I’d take gallon cans from the school cafeteria, cut off the top and bottom, peel off the labels, and draw patterns on them. That was hard because the can was tin and the radius was tight, so the blade would slip. I wound up cutting myself a lot because the blade would skid off. I finally got the idea to get some drums to try it on. At the time, nobody wanted 1920’s six-lug drums. They were the bane of everyone’s existence because most drummers were looking for 8- or 10-lug drums. Everyone was looking for parts like tube lugs, collar hooks, and strainers, but there was no real network to look for them other than getting on the phone or writing letters. I got the brilliant idea to take the tube lugs off the 6-luggers and sell them, then use the 6-lug shells to practice on. I would sit on the merry-go-round at lunch time. A little kid would sit beside me and say, ‘Mr. Aldridge, draw me a horse.’ I would draw/engrave a horse free-hand on the drum. The next kid would come along and say, ‘Mr. Aldridge, can you draw me a butterfly?’ So, I’d engrave a butterfly on the drum. They inspired me to try things a bit more free-hand but I realized that it wasn’t very consistent. I started looking back at the patterns the engravers used on the vintage drums. I traced those out and used them to practice with. I finally got up the gumption to do my own Black Beauty. I bought a 1980’s Ludwig bronze Black Beauty and engraved a flower pattern on it. The details were completely inaccurate, but that was my first engraved Black Beauty.

I did engraving for about 5 years for myself and a few friends. Around 1989, things started happening for me. Harry Cangany (Indianapolis Drum Center owner, author, and vintage drum historian) called and asked me to do a 6.5” Black Beauty as a gift for Kenny Aronoff. Harry kind of became an ambassador for me. He was one of Ludwig’s biggest dealers at the time and he took pictures of the drum and sent them to Ludwig, telling them he thought there was a market for engraved drums. Shortly after, I got a call from Dick Gerlach, product specialist at Ludwig, and he asked me about my engraving. I was pretty over the moon about that and had just about finished the three prototypes when Don Lombardi called me from DW. They sent me some shells to try, but at that time they were using shells made offshore that didn't really work well for engraving. They were hard to cut and not extremely well constructed. I did one for Tommy Lee, then Rikki Rockett, and Larrie Londin; a total of around a dozen mostly for their artists back then. Most of those drums had scratches that got covered with other engraving!

The vintage drum business also brought me an engraving customer in the form of Jon Cohan, proprietor of Drum Heaven drums. I engraved brass hoops for the drums that John built using Eames shells. Jon was responsible for introducing me to a lot of people in the drum industry that have continued to have an effect on my life. He's also a genuinely caring person who has been there to listen when things went south for me. Jon no longer makes drums, but he still plays and is now a substance abuse counselor in the Boston area, working to help musicians and others who have gotten sidetracked to get their lives back together. I provided engraving to Drum Heaven from 1992-97, and still do the one-off custom project with Jon when he gets the itch to build a drum.

Ludwig called back about their 1990 run of drums. They had sent me three shells (3 x 13”, 5 x 14”, 6.5 x 14”) and asked me to engrave three different patterns. They didn’t know what patterns to put on them. They just told me to find the appropriate vintage patterns and use them. Since they were using Imperial lugs rather than vintage tube lugs, everything had to be re-sized to fit into that space. The patterns prior to that went right up to the tube lugs. I made the adjustments to make it work and not run under the Imperial lugs. When I first started engraving the 6.5” snares, I ran into some problems. With a lot of them, it would first be like cutting through melted butter and then suddenly it would be like concrete embedded in glass. The blade sound would change, and I’d have to apply about ten times the pressure. So hard that I could barely hold the drum. It was because the shells were not annealed (a heating process which alters the physical properties of metal to make it more pliable and reduce its hardness). I did about 50 shells for Ludwig, but about every third one would have a scratch. I was living in Boulder, Colorado, so they were having to spend money to ship them to me, and Ludwig’s policy at the time was that any drum with a scratch got crushed. They could only use two out of three shells I engraved. They were no happier with the situation than I was, and it was costly to destroy 1/3rd of the production. But the idea of annealing the metal to prepare it for engraving hadn't entered my mind yet! Then another engraver named Reid Smith contacted Ludwig. Reid was a trophy engraver in North Carolina who lived only about 10 miles from the Ludwig factory. My understanding is that he underbid me for the contract. Ludwig then gave Reid the contract.

Just after Ludwig's production stopped using me, I hooked up with Todd Trent in Artist Relations for Ludwig (and President of Ontario Music Inc.). Todd wanted me to do custom engraving for artist relations even though I wasn’t doing any production drums. I could buy the Ludwig drums from Todd, take all the Imperial lugs off, and replace them with brass tube lugs made by Don Corder. I would plate all the hardware in copper or brass. I offered a scroll-engraved Black Beauty at the time when Ludwig offered their flower-engraved version. Over the course of those 8 years, I engraved probably about 250 drums for private customers.

I didn’t engrave any more production drums for Ludwig until 1999 (90th anniversary), other than a couple of one-offs for artists that they wanted. They figured out pretty quickly that the shell scratching problem wasn’t me; it was their shells that caused the engraving problems. Reid was able to point that out to them. After about 400 drums, they discontinued the engraved Black Beauties. When they asked me to do the 90th Anniversary, they started annealing the shells.”

NSMD: How did you get back into engraving for drum companies?

“Shortly after I lost the first Ludwig contract, my wife graduated with her Ph.D. and we moved to Vermont for her first job as Doctor Aldridge! Not So Modern Drummer magazine was really growing and engraving was doing well, so I decided to retire from teaching and focus on playing and my other drum related ventures for the foreseeable future. I was still customizing Ludwig snares, as well as custom drums for individuals who sent their own drums, and had just started buying Slingerland drums from my friend Buz King, who was in charge of Slingerland licensed products. I engraved a few drums for him to display in the HSS (Hohner, Sonor, Sabian) booth, but by the time I got to the NAMM show with the drums, Slingerland had been sold to Gibson! So I took the drums over to the Gibson/Slingerland booth and made the connection to continue engraving for Slingerland.

In 1994, my son was born, and my wife and I decided that she would stay home until he was school age. Thinking that I'd be better off closer to the company I was working with; I gave up the playing side of my career and moved to Nashville. I intended to engrave drums for Slingerland and pursue the Not So Modern Drum Company idea that was starting to eat up all my spare thought. Very shortly after the move to Nashville, Slingerland was closed and packed up in the first of many changes for that company. I was stuck with no company contract, engraving drums, writing for any drum magazine that needed a review or article on vintage drums, and publishing Not So Modern Drummer. Around that same time, Johnny Craviotto had just gotten in with DW (Drum Workshop). Johnny called me to do engraved rims on some drums for a Johnny Craviotto/DW drum. Johnny and I were rabid vintage drum collectors and had been friends since the early 1980's. He did everything he could to steer business my way when Slingerland stopped.

If you ever want a recipe for losing money, just follow my career up to this point and you will succeed. Thankfully, my friends in the business helped me to get past this spot and on to the next project. I managed to make it pretty well until December of 1996 when the roof fell in on me (not literally). I had started Not So Modern Drum Company with a partner in an LLC. We were attempting to make a modern reproduction of the 20's Ludwig Black Beauty from the ground up. This was a no-win proposition for us, as the people who'd made those parts were long gone, and nobody used those methods of construction anymore. By the time I wised up and decided to move on and get my money back from the metal spinners who couldn't get the job done, it was too late. In a sequence of events that fell like dominoes, my son was born with complications ($60,000 doctor bill), the metal spinners declared bankruptcy ($48,500 loss of mine and investor funds), my partner skipped out on his lease (I was sub-leasing), and I had to move my business. . . all in one week. That week and the fallout is a book in itself, one that I don't like reliving. But in the end, I got a happy, healthy son, moved out of a toxic business relationship, and focused my business on paying back all the debt that I incurred virtually overnight.

I used the Not So Modern Drum Company brand and partnered with Walt Johnston at Worldmax to build the parts I needed to make an affordable Black Beauty sound-alike, look-alike, but with some tweaks to the shell design to make it sound like older Black Beauties. It wasn't a perfect drum but look around you today and you'll see a bunch of very familiar shells being used by just about every custom drum company in business. That wasn't happening before 1996. Most of the drums I built for the next ten years depended on Walt to produce a new size or finish for the parts I used. Gradually other custom drum companies started using Walt's Worldmax shells and shortly after, making the same things for themselves! There are only a couple of completed drums from the original NSMD company remaining today. One was engraved and gold-plated for one of the original investors, and I have the other one. Neither is perfect, or even a good example of what I was going for in the first place. But they do sound good! (

editor’s note: Not So Modern Drum Company engraved drums are still available on a custom order basis; still engraved by John and still using World Max Shells. contact George Lawrence george@notsomoderndrummer.com)

When Ludwig’s 90th Anniversary came along in 1999, they called me about engraving some drums. I said, ‘OK, but this time you’ll have to sign a contract. That actually worked for me! They signed the contract, and we had a great run of 90 drums.”

NSMD: How did you get involved with TAMA?

“Kenny Aronoff came to town one day and we went out for lunch. Kenny said ‘Tama has offered me my own snare drum. I want something Black Beauty-like. What do you think I should do given what you know about Tama and their parts?’ So we sat there and talked while he figured out which of Tama’s parts would come closest to a pre-serial chrome-over-brass (COB) drum. That’s how the Kenny Aronoff ‘Trackmaster’ snare came up. Kenny wanted me to engrave them. I did about five of these drums and then nothing else came along. It turned out that Tama had found a supplier in Taiwan who would do the engraving for about a third of what I charged. To me, it looked like it was done by a child with a not very sharp rock. It was really bad. I told Kenny about it and he blew a gasket. He called up Tama and soon after I had a new contract to engrave the Kenny Aronoff Limited Edition Trackmaster. For that (in addition to his stellar drumming), I have the utmost respect for Kenny Aronoff. I wound up doing 72 of those drums over the next two years. I was doing everything on those drums. They were sending me a box with a snare drum shell and all the parts individually wrapped in plastic. I engraved the hoops, lugs, strainer and shell. Then I took them across town to a guitar tech who built a rig to spray lacquer. He’d apply the lacquer. I would assemble the drum, put it in its velvet bag, place it in the box, and ship it to Tama. They would then send out to the dealers. I’ve since done a few more things for Tama, mostly on-offs for their artists.”

NSMD: How can a person tell which Trackmasters were done by you if they don’t have a keen eye for engraving? Were they only the ones with lugs engraved?

“You can identify my engraving on Tama drums in two ways. If the lugs, hoops, shell and strainer are engraved, I did it. If just the shell is engraved, you can tell by looking through the venthole in the drum for my JMA stylized initials, engraved inside the drum. There are only five or six of the latter!”

In the middle of all the Tama work and the Ludwig 90th anniversary snare drum in 1999, Johnny Craviotto started off the Lake Superior drum project. The first run was maple and had gold-plated hoops which I engraved. We did 200 of those. We did another run of 100 birch shells with nickel-plated, engraved hoops. At one point, I had to hire a secretary to sit in the office for Not So Modern Drummer and answer the phone. I would go sit out on the loading dock in a chair and engrave hoops, lugs, strainers and shells for Tama, Ludwig, and Craviotto/DW. That went on for two years. I was still engraving drums for Tama when I left Nashville in 2001.

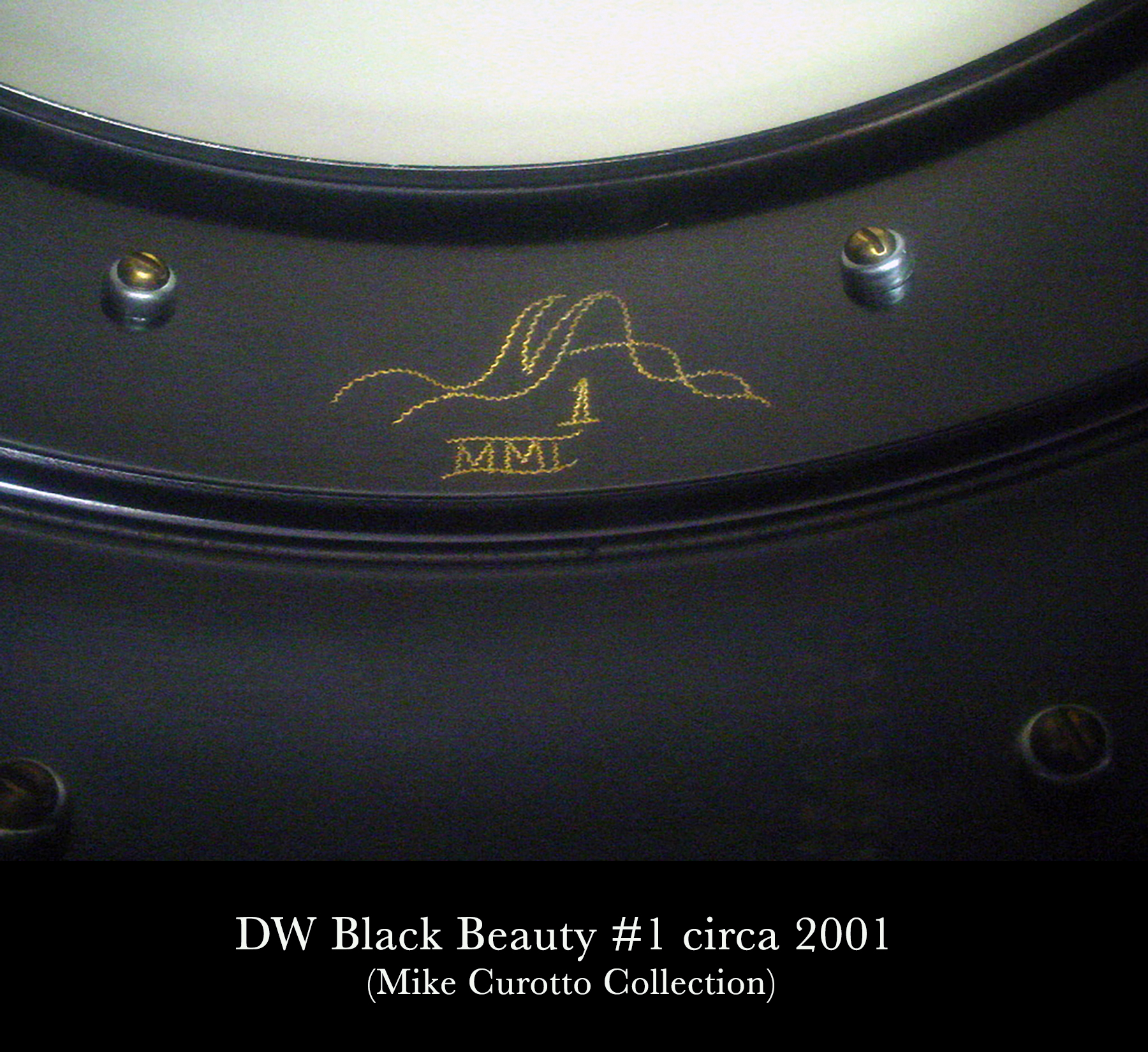

My wife had gotten an offer to teach at a university in Oklahoma. I opened up a little shop in downtown Shawnee, a typical small town just outside of Oklahoma City. Eventually, I moved my business out of the storefront and into a garage when we bought a house. I was doing my drums (Not So Modern Drum Company), the Craviotto Timeless Timbers, and the Tama Kenny Aronoff Trackmasters. As those were winding down, I did a project with DW on their Black Beauty that amounted to 69 drums. Those I’m still doing one-offs once in a while. I kept up the numbering. DW had very little interest in that line and discontinued it. Those up to 69 are the production run, and those after are the after-market that look exactly like the original product. That was around 2000-2001.

I kept doing (engraving) a lot of individual drums and working on the magazine (NSMD) until about 2005. Ludwig came back in 2005 and wanted to do about 150 limited edition engraved drums. I don’t know why as it wasn’t a special anniversary or anything. I finished that run in 2007. In 2008, Ludwig called back to discuss the 100th anniversary, which was another 100 drums. Over the process, about twenty of them had plating problems, a scratch that was my fault or some other problem. These became seconds. I got four of them back and nickel-silver-plated them. That’s what Bryan (Hitt, REO Speedwagon) plays to this day. My son Lucas also has one of them, and I sold the other two for more than the limited edition black beauties!”

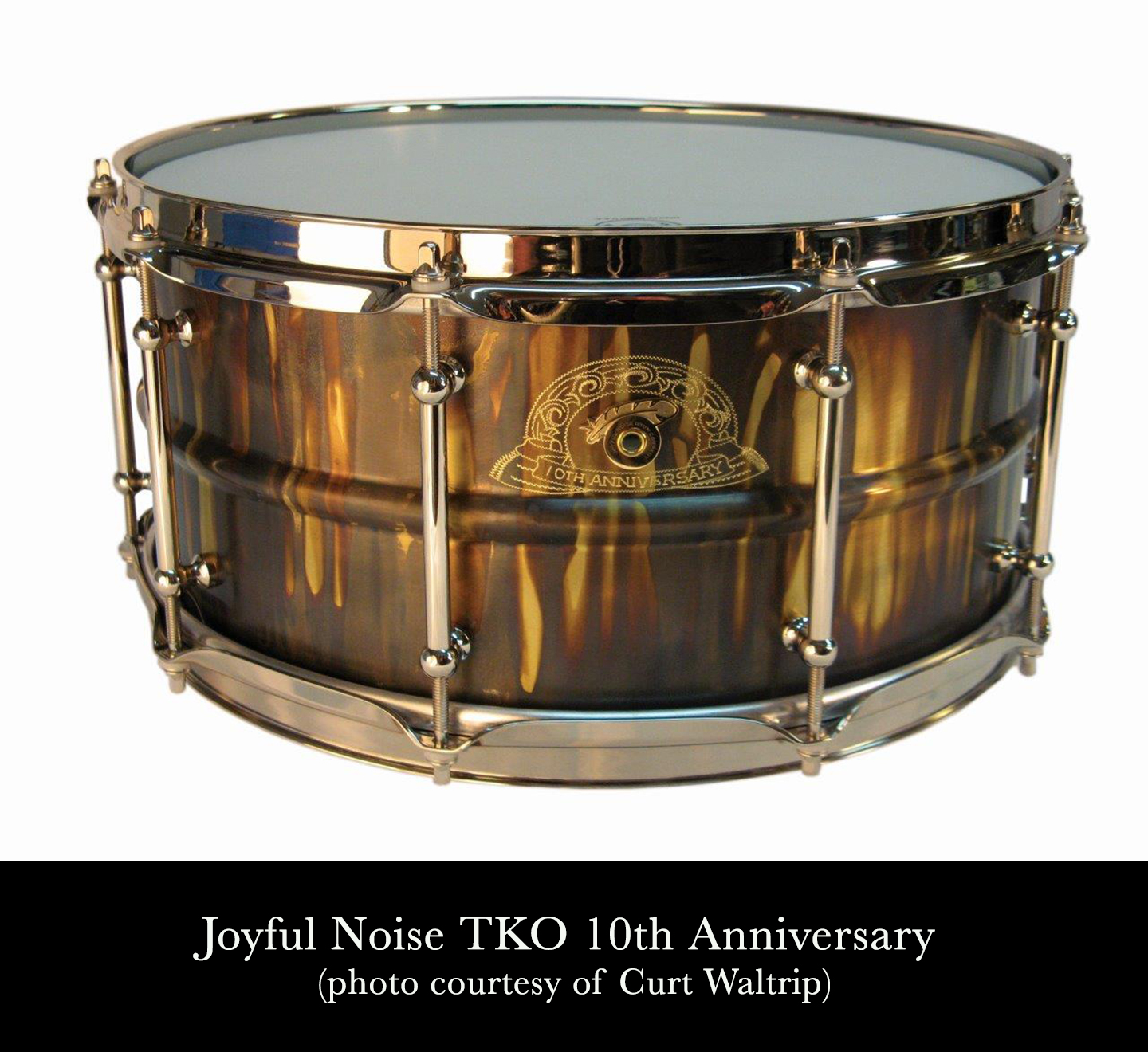

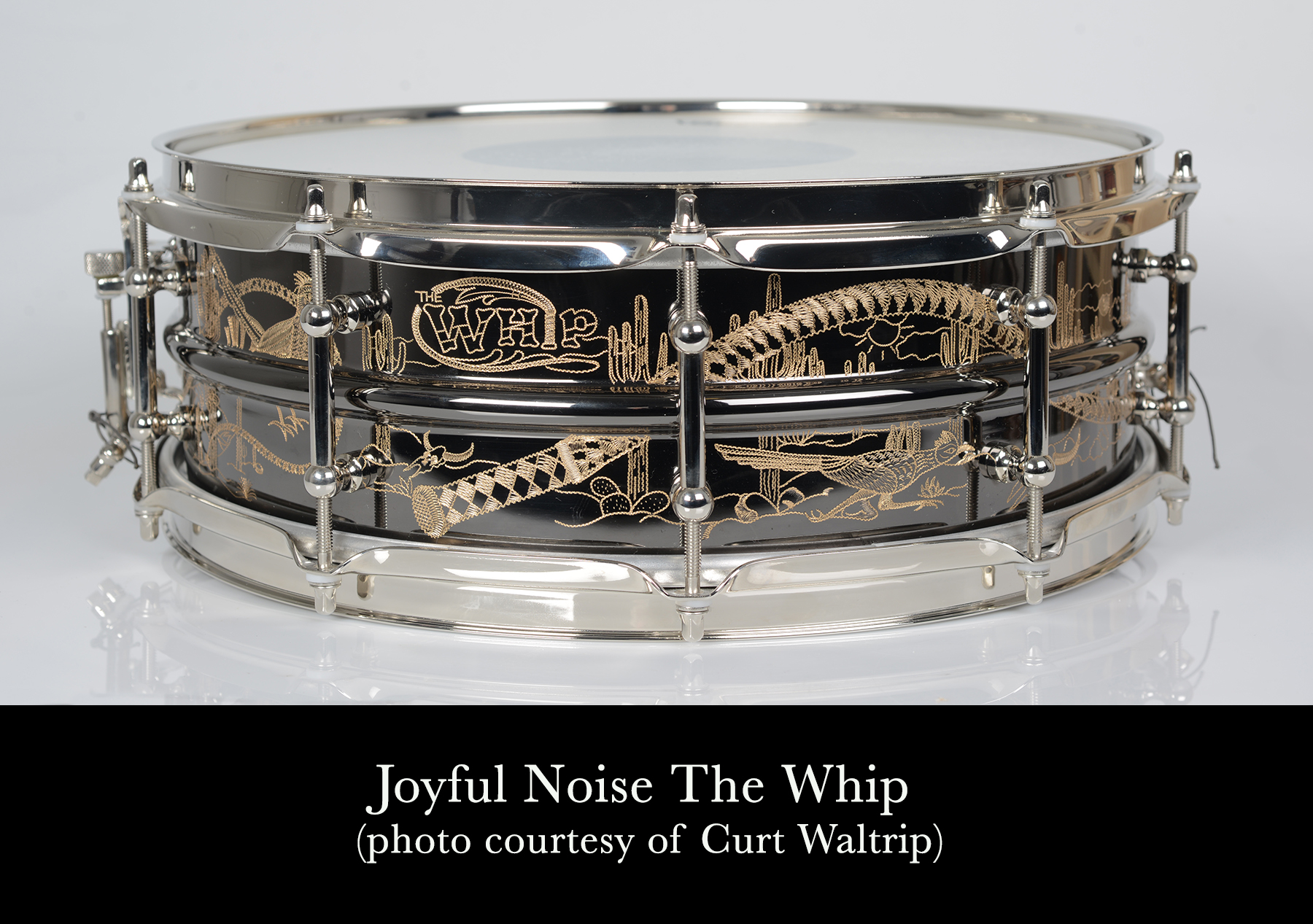

NSMD: How did you get involved with Joyful Noise Drums?

“Kurt Waltrip (Joyful Noise) called me when he was thinking about building his drums. He started talking about spun shells and so on. I finally stopped him and said, ‘You’re trying to do what I did, and I screwed up horribly.’ He said, ‘What do you mean?’ I told him that everything he was trying to do I had already done. I replied, ‘I could tell you how not to do it. I can pretty much steer you the right way on how to do it. By learning from my own mistakes, I think I’ve learned where to go.’ That was the start of our relationship. My phrase to him was, ‘Let my ceiling be your floor’, and that’s what it’s been. I’ve tried to act as a mentor. Joyful Noise are very high-quality drums and made in the United States. Every person that touches those drums is a craftsman. I engrave on several models specially built to dealer specifications. He has one called the Blackbird model. It’s sold exclusively through a studio in Nashville. That was just going to be a one-off. We’ve probably done 30-40 of them so far. It has just one panel I engraved with the blackbird logo around the Joyful Noise badge. Memphis Drum Shop has their own logo, ‘Memphis’, (e.g., Memphis Studio Line bronze snare), and Drum Center of Portsmouth has a lighthouse (e.g., Beacon bronze snare). All of these are engraved around the Joyful Noise badge. For C&C drum company, on their metal shells I put two little circles and an interlocking ‘C’ on them.”

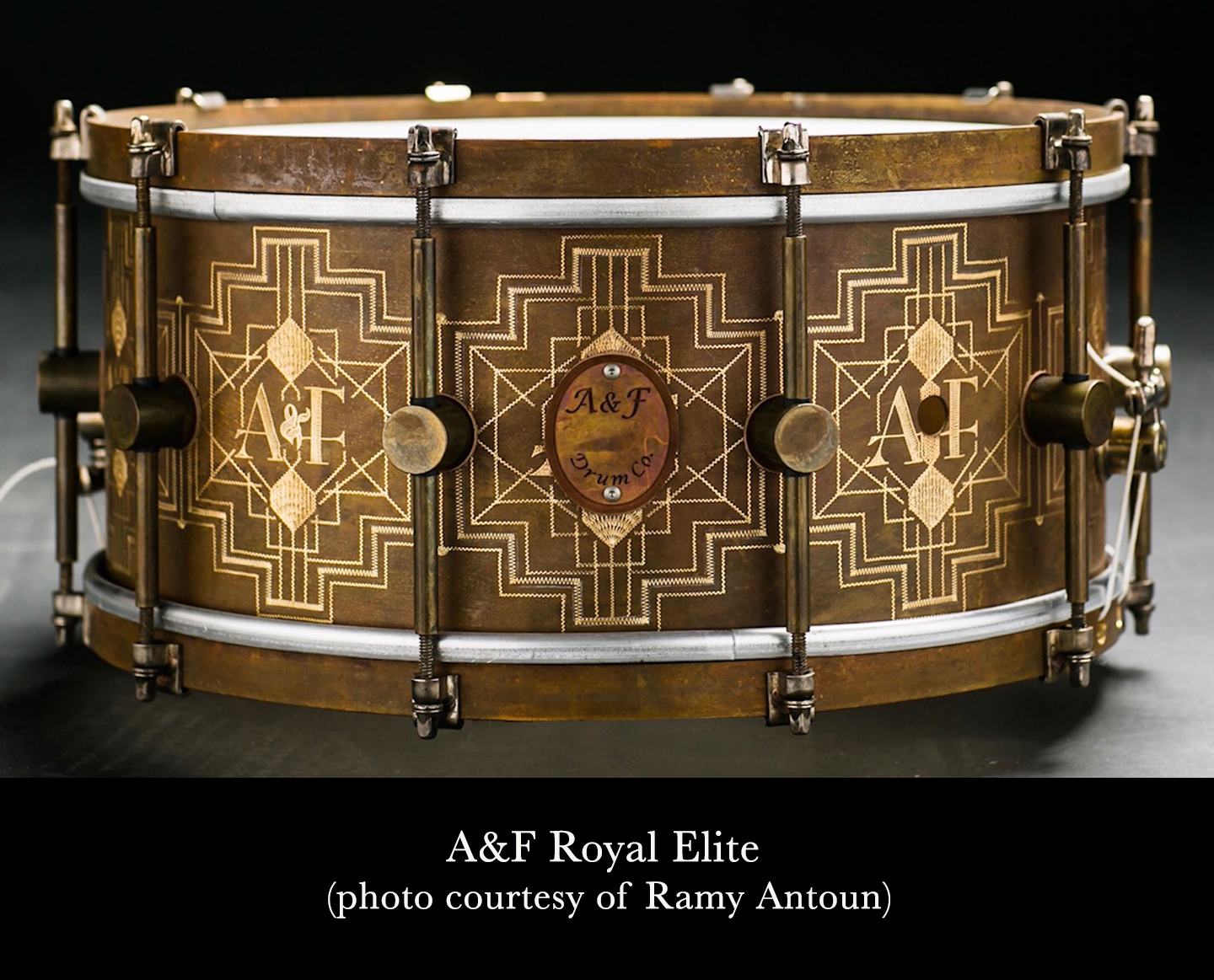

NSMD: Could you tell me about your recent work with A&F Drums?

“I’ve been doing a lot of A&F drums lately. I met Ramy Antoun when he was very young and working at Sound City in Hollywood. He was doing anything he could to get into the music business. The story goes that one day, somebody told him to go in and tap on the drums for a sound check. The guy told him to play a little bit and the guy said, ‘Oh, you’re a drummer. Play a little more for me.’ So Ramy played for a while. The guy came back in the room and said, ‘You shouldn’t be doing what you’re doing. You should be doing this. You should be making records.’ That started his recording career. He ended up playing and writing music with Seal.

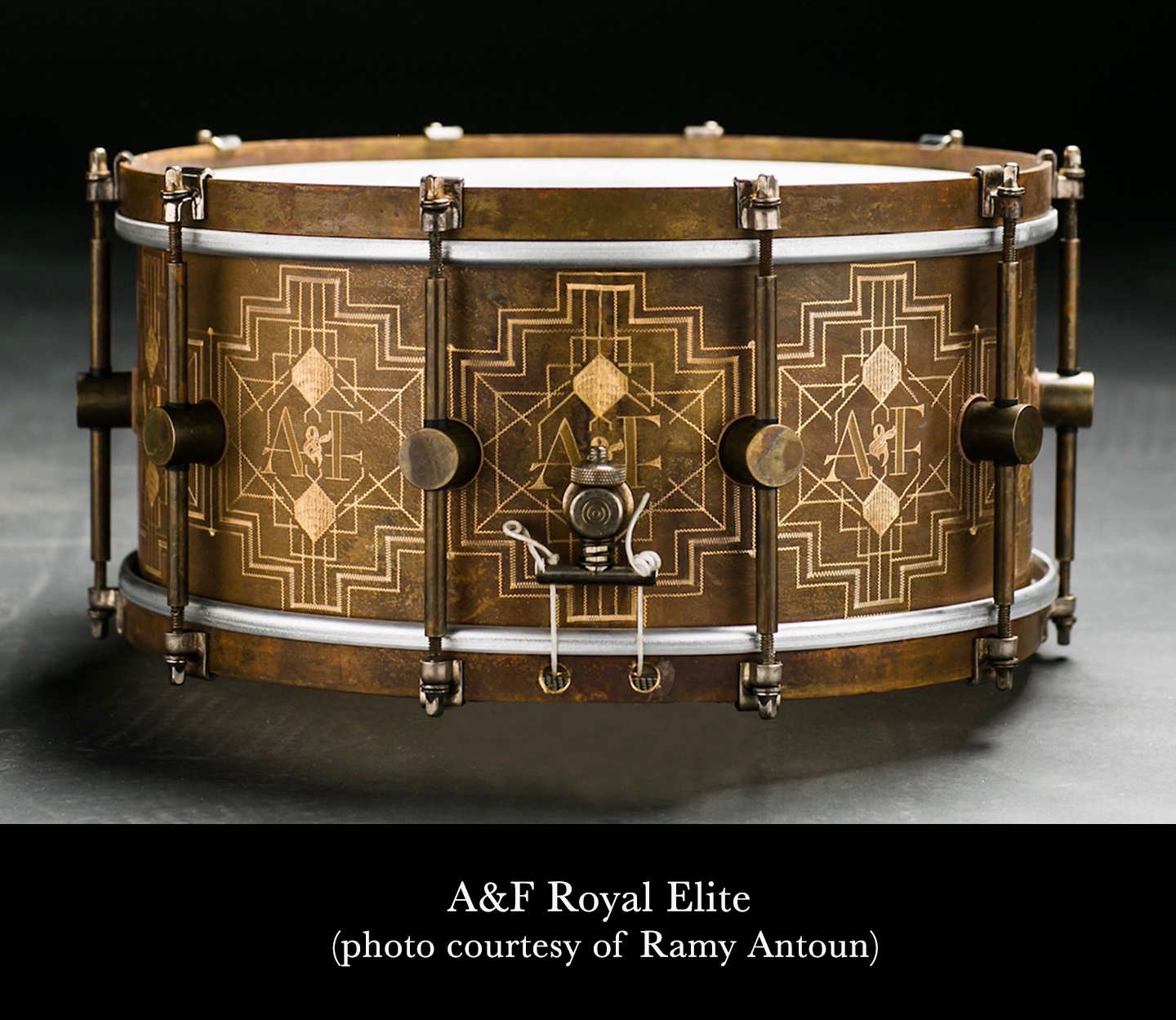

Now he’s the man behind A&F Drum Company. They have a little oval logo with an “A&F Drum Co” that they use for their badge, and it also appears in all of the engraving patterns I do for them. Ramy (Antoun) builds a wide range of drums. I think I’ve engraved at least half a dozen drum sets for A&F this year (e.g., Royal Elite). He generally goes for a simplistic approach but always puts the “A&F” in every pattern. Ramy said something like, ‘I want it to be like Abercrombie & Fitch – big, bold and right there. I want it to be part of our identity.’ I can’t say he’s wrong because he’s sure selling a lot of them!”

NSMD: How did you land the REO drum tech gig?

“In 2000, right after I moved to Oklahoma, I went to a doctor because I had this zit I couldn’t get rid of on my nose. The doc said, ‘I wouldn’t worry about that zit. It’s that cancer right next to it that you should worry about.’ He whipped out a scalpel, numbed it up, and took out about a ½ dime-sized chunk out of my nose. Then I did six weeks of radiation therapy. Even though it wasn’t life threatening and I came out of it smelling like a rose, it was a wake-up call to make me look at what I was doing and where I was. At that point, I was still in my little shop. Not So Modern Drummer was slowly going down as the internet took off. I was just doing custom drums and the magazine. It wasn’t really enough to make us comfortable as a family. My wife worked full-time, so we had great benefits. But I had two growing kids and they needed stuff. One day, I was sitting with my wife in a restaurant and said to her, ‘Honey, once before I keel over, I’d like to do one more rock show.’ Although I was never a touring drummer, I'd always wanted to be a part of that world. My wife said, ‘No one is going to hire a 45-year old, overweight, cancer-ridden drummer (laughing).’ But I told her, ‘You’re right, but they’ll hire me as a tech because everybody knows me and I know how to put a drum together and tune it.’ With that said, she replied, ‘Yeah, good luck with that’ and never thought anyone would bite.

I put the word out through Todd Trent (former A&R rep for Ludwig, President of Ontario Music, now drum tech for Cheap Trick) and some other guys that I wanted to go out as a tech. The first guy that called was Jack Bruno, a good friend who played drums for Joe Cocker and Tina Turner. He asked me if I would go to Europe and Asia for 8 months with him for a Joe Cocker tour. I wasn’t sure I could go on the road for 8 months right off the bat after my radiation treatment and all that. I also didn’t want to be putting his current tech on the street for a year. I passed on that one. The next day, Bryan (Hitt) called. He had a tech that was wasn’t working out. Bryan wanted to know if I would come out and sub for about two weeks while he looked for another guy. He said he couldn’t hire me because I lived in Oklahoma. He’d have to fly me out to L.A. every time he wanted to rehearse. So, I said yes to subbing. I was just about ready to head out when he called and told me he couldn’t let go of the other tech right now. It seems that the crew didn't think he'd gotten enough notice or a fair shake in doing the job. I got kind of angry at the situation, not with Bryan. But it was frustrating to get geared up to go and then get shut down.

My wife and I went out to New Mexico for a little vacation and came back to find a message from Bryan. Things had come to an end with Twig, so he asked, ‘Would you still consider coming out? I said, ‘Yeah, sure, when do you need me?’ Bryan said, ‘Tomorrow?’ They booked me a flight for 5AM the next morning. I flew in for my two weeks tech-ing with Bryan. I brought a box of drum shells with me to engrave. I had so much stuff to work on that I didn’t figure I could go two weeks without engraving. It turns out I never got the time to touch those shells and took them home to finish them.

I got to the end of the run. I was at a hotel in Atlantic City, and Bryan called me on the phone. He asked me, ‘What are you thinking?’ I said, ‘I was just going to ask you. Did you need me to train your new guy in L.A.?’ He goes, ‘Well no. Don’t you like the gig? It’s yours if you want it.’ I was confused so I said to him, “What about the Oklahoma thing?’ He then says, ‘to tell you the truth, we just thought you were sitting behind a desk for too long and wouldn’t be able to cut it. We wanted to let you down easy and not hurt your feelings if you couldn’t do it. Go down to the tour managers room and he’ll explain how the money works to you.’ The tour manager (Walter Versen) explained how the pay schedule worked and a few details that hadn't come up yet and suddenly, I had a new full-time job.”

NSMD: Are you still doing a lot of engraving?

“Right now, A & F, Joyful Noise, and my custom jobs are keeping me pretty busy, but I've always got time for one more! I've recently completed a couple of ‘Private’ limited editions for drum shops celebrating significant anniversaries. There were 25 custom engraved DW black beauties for Dana Bentley's drum shop, and another 30 custom DW snares for Jim Pettit's Memphis Drum Shop's thirtieth anniversary. I'm just finished a limited edition for Eric Singer (KISS) to sell as part of his meet-and-greet experience for the KISS: End of the Road tour.”

NSMD: What do you do in all your "spare" time nowadays?

“I've started building racks for other drummers. The REO kit started this hobby, and I was motivated by my desire to get rid of the 10 tripods on the drum riser! Bryan didn't like racks, and I agreed that I didn't like the way most folks built racks in the standard U-shaped rail with drum hardware attached. Bryan's pet peeve was that he hated that bar across the bass drum that was so prevalent. I took that as a challenge and first just built a stealth rack base on each side and another between the double bass drums to support the two toms and snare drum. Then I removed all those tripods from his stands and attached them to the two curved bars of each stealth rack. From the front, you couldn't really see it, but all the stands that were so hard to place on the riser before were nicely lined up in a curve on each side of the kit once the tripods were out of the way. I've recently built racks for Tesla using Tama hardware (current tour and one yet to come) and the two racks for the current KISS tour using Pearl's rack system. I usually work with whatever brand of hardware the drummer is endorsing, but I really like Gibraltar's clamp and bar options, which I use on my own rack at home and on Bryan's kit.”Looking back, everything I’ve done has kind of evolved from something else I’ve done, and people I’ve met along the way. If I had one over-arching rule, it was ‘if you really want to do something and are passionate about it, go do it. Somebody’s going to buy it. It’s held true for everything I’ve done, from Not So Modern Drummer to Not So Modern Drum Company to engraving, and now being a drum tech for Bryan Hitt. I’ve been doing that (drum tech) now for 14 years and it's the longest I've held a job with a single employer in my life!

NSMD: Any words of wisdom from your many years of experience as an engraver?

We tend to glamorize engravers of the past as being "master engravers". Some years ago, that term got applied to me, much to my chagrin. A master is someone who concentrates all their efforts on a certain skill to the exclusion of all else, and through that extraordinary focus, are able to produce incredible, unique works of art. There are engravers working today, including my contemporaries in drum engraving, who are masters, but I'm not one of them. In my scheme of things, engraving is something I do to fill a desire to make drums look a certain way. But if I did nothing but engrave, I would be stark raving mad in a few months. The men who engraved the vintage drums that inspired me were factory employees, just like the guys who made the shells, painted the heads, tucked the heads and assembled the drums. There were definitely master engravers at that time, but they weren't engraving drums! A drum factory didn't pay "master engraver" wages at the turn of the century. Engraving was a skilled labor and was usually learned through an apprenticeship. I would classify most of the engraving on vintage drums as work of craftsmen who were more apprentices and journeymen rather than master engravers who produced art for art's sake. In that way, I'm more like the factory engraver than an artist. After 35 years I'm beginning to develop a more artistic way of looking at the patterns, but I still engrave vintage patterns and customer artwork more than I do original ideas from my own brain. And while most people will never look closely enough, I can point out the multiple flaws in just about every piece I've ever engraved.

I never had a burning desire to be a graphic artist or engraver. I got into engraving because of drums. I wanted an engraved drum but couldn't figure out a way to afford it! I was a working drummer, working local gigs and teaching. There was no way anyone would consider me a world class drummer, but in the microcosm of drum engraving I was given instant "master" status by folks who liked my work. Why? Because I was the only work they'd seen! If I'm considered ‘World Class’, it's because my class is so small! Currently, I only know of 6 people engraving drums for the modern drum industry in the USA. I would only consider one of them to be a master engraver, and that's Adrian Kirchler. Adrian is an engraver who discovered engraved drums and applied his considerable skills in a new area, whereas I'm a drummer who figured out how to engrave. There are many engravers still plying the trade in other parts of the world that no one reading this story has ever seen. My claim to fame is that I was the first person to remind folks in the drum industry that this art form still existed and could still be affordable. Because I was the first to shine a light on engraving, I get a lot of credit. But if you think about it, anyone who wants to engrave drums can do it if they want to bad enough. The few who've observed what I did and taken it to the next level are the ones I admire.”

Stay tuned for The Drum Engravers – Part 2!

Testimonials:

Mike Morgan (drum engraver): “At this point in time, John’s work far exceeds the quality of the early commercial engraving on the original Black Beauties of the 20's and 30's, and it continues to evolve to this day! This can’t be attributed to ‘modern tools and techniques’ because John uses the same basic tools and methods from the past. This can ONLY be attributed to reaching a higher skill level than the original craftsmen of the past. Kudos to you, John. You've earned it!”

Adrian Kirchler (AK Drums, drum engraver): “John is THE torchbearer of an art that was nearly lost. His research of early 20th century engraved drums in conjunction with his mechanical skills led to worldwide success. He was (and he constantly still is) working for many of the big names in the industry, as well as for countless famous drummers. This alone speaks for the quality of his work and for his excellent reputation! Without a doubt, John was my source of information regarding vintage drums and my inspiration to try out drum shell engraving in the early beginnings. Although we’ve met in person only once (at an early drum show in Amsterdam, NL), we are in loyal contact since all these years. To THE ‘drumscratcher’ with sympathy, sincerely, Adrian.”

Ronn Dunnett (Dunnett Classic/George Way): “It is a blessing when you have a genuine connection with an artist - even if you’ve never met or spoken to them. I am very fortunate to know John personally and through his work. I suppose I could say he is the world’s finest engraver of drums (certainly the most prolific!), but then it really isn’t giving him the credit he deserves because John is in a class of his own. His work has kept the art of engraving alive and well within the drum community and I think we owe him for that. He is a wealth of knowledge when incomes to drums, and I have to say - I love listening to him - he is an American treasure.”

Curt Waltrip (Joyful Noise Drum Co.): “John is a rare member of our drum community. He possesses an extremely deep understanding of the history of drum designs and manufacturing, as well as the drum companies themselves. He is truly unique in that he will freely give anyone the benefit of his wisdom and knowledge, as it relates to “all things” drum. He will help you to make a difference in the industry, if you are open. But John is also very diplomatic. If your idea is not that good, he’ll kindly say, “Are you sure you really want to put that on a drum?” What makes John unique as an engraver is that he has extensively studied the metallurgy, design patterns, and history of the drum. From a technical standpoint, his engraving exhibits very deep facets, resulting in the most reflective patterns. That means his cuts are deep and crisp. There’s never been an engraver like John. He’s more than just ‘a guy who just engraves drums.’ “

Ramy Antoun (A&F Drum Co.): “John is one of those very unique guys that shows up with the most humble disposition, only to leave one of the deepest imprints imaginable. From his absolutely incredible mastery of engraving, to his depth of knowledge on the history of this beautiful instrument, to his credited wisdom and lived experience in this business, we look to John as our mentor, advisor, and encourager!”

Mike Curotto (Collector, Author, Drum Historian): “I first met John Aldridge in my early days of collecting, March of 1995. He was always kind to me and always took time to answer my questions. To this day, I consider John a very good friend and a great vintage snare drum source. I have nicknamed him “Oh Plethoric One” for the plethora of vintage drum knowledge he has. John got me interested in collecting 1920s-30s Ludwig engraved DeLuxes (Black Beauties as we call them). I have bought many cool snare drums from John, and he has helped me to score many more snare drums. I still have John’s first NSMD engraved “Black Beauty” #1. I have a section in my home that I call the “John Aldridge Wing” in honor of all of the snare drums that he has helped me to find. Thanks for everything John!”