by Ulysses Owens, Jr.

When a drummer starts learning the drum set, they are given a pair of drumsticks and a practice pad or snare drum and they are taught the rudiments. Many of them will never march in a drum or bugle corp nor will they ever venture into classical snare drum studies, but we all agree this is the method and tradition of learning how to play the drums correctly. That same student is taught a rock, funk, or latin groove and their fascination with the drums continues.

Why then is that so often the same drummer is not taught a swing groove, or given a set of brushes? Especially when historically the “trap set” was erected out of the jazz tradition, and through jazz music, the evolution of the drum set continued until about the 1950s when the early iterations of rhythm and blues and rock n roll music entered the mainstream music world. Clarifying that the evolution of drum set playing is rooted in jazz music, it makes sense the brushes should be part of every drummer’s journey.

You may ask, “Ulysses what if I don’t play gigs requiring brushes?”

I believe for any musician who plays the drums, it doesn’t matter. Learning the brushes is part of your due diligence on the drum kit.

You may also ask, “Where do I start with learning about the brushes?”

I suggest you pick up the Ahmad Jamal Trio recording “Live At The Pershing,” and lis- ten to Vernell Fournier. The rest is history.

The great Dizzy Gillespie stated, that for one to evolve in a holistic way in music, you must have one foot in the past and one in the present, and they will determine an ade- quate future in the music.

Just pick up a pair of brushes, and start learning – because if you want to be a drummer that has a complete understanding of the kit, eliminating the brushes will not lead you there!

My Love Affair With The Brushes

I remember listening to the record that I mentioned earlier – Ahmad Jamal’s “Live at the Pershing”, featuring Vernell Fournier on drums. I still remember the first pickup on “But Not For Me.” It forever changed me. A few things that stood out to me were, wondering how this drummer is getting such a big sound with the brushes, and also the consistency of the sound of the brushes. Vernell’s articulation is so incredibly clear. Also, his ideas grooved so beautifully and his integration of the bass drum with the brushes was also noteworthy. I could tell that he spent a lot of time playing with Ahmad too, because there was this seamless connectivity within his playing. So I began to use this recording to focus on a few things in my brush playing because I was still new to learning the art form.

I spent time just simply playing with records that had drums and also those without drums because my goal was to make the record feel just as good as if I was there with the band in person. I never got to play with Ahmad Jamal, but playing along to his records were the next best thing.

I transcribed specific ideas from Vernell – I literally transcribed all of But Not For me but as an “oral tradition” type of transcription – by ear. I prefer the act of listening to some- thing receptively and learning straight from the record without writing out what you are learning. I find this way the ideas remain part of my vocabulary, as opposed to when I have learned written transcriptions – where I find I am focusing on what’s on a page.

With Vernell, I also studied the few videos that were out there, and I spent a lot of time speaking to people that played with him. I checked out his technique. A key entity about Vernell is the width of his brushes, which was really narrow. To me, it made his sound that much more virtuosic and this taught me a great approach for playing good time and fills with the brushes.

How to Play Good Time with Brushes

After spending a great deal of time with Vernell’s records, I realized that I wanted to embrace and add a new method of playing good time with the brushes.

The first thing I want to establish here is that to play good time with the brushes, you must learn how to play without the hi-hat first. Earlier in my brush playing years I, like many drummers, spent a lot of time hiding behind the hi-hat. What happens is you play the pattern, and your sound isn’t clear, the left hand lacks definition and the strong 2 & 4 on the hi-hat allows you to feel somewhat adequate.

This happened to me until a wonderful jazz guitarist in NYC, Nick Russo started calling me for gigs every week when I was still in college. We would play a few restaurants in SoHo, and he would say, “Ulysses just bring your snare drum, a stool and some brush- es because we don’t have room for much more. See you at 7!” So here I was with my mediocre brush playing having to play a weekly 3 hour gig with guitar, bass, drums,

and a singer, and I had to find ways to make a snare drum and brushes sound like a full kit. It taught me how to dig deeper into the snare drum, and get sounds out of the drum with brushes. I also learned the various timbres and tones within a snare that I could access that could have the same range as a drum set. This helped me to devel- op good time with the brushes so, even, when the hi-hat is present, I don’t need it.

The second record that helped me was listening to Tommy Flanagan’s “Overseas” record featuring Elvin Jones, who plays brushes on the whole record and Johnny Hartman’s “I Just Dropped By To Say Hello." These records showed me the versatility a drummer like Elvin could possess. We all worship Elvin musically but realizing that he also understands the brushes, and the sensitivity that comes along with the art form. helped me learn to utilize all of the important time-keeping techniques available – but not at the expense of your sound and personality. Elvin still sounded like Elvin with brushes, and much of his trademark fills and “Elvin’isms" were, even with only brushes, still very much present on this record.

One of the greatest living jazz drummers is Kenny Washington aka “The Jazz Maniac,” who happens to be one of the greatest brush players in the history of the music. I had an opportunity to study with Kenny, and just one lesson, where we spent the whole time speaking about the brushes, changed my life and I’ll never again approach the brushes the same as I had before. I took a lesson with him at the urging of Eric Reed, who was mentoring me at the time and, though I was taking lessons at Juilliard, I paid out of my pocket to go see Kenny which was worth every penny and so much more.

Kenny asked me if I played brushes, and I said “Yes,” – and that I was good! He said, “Well, let me see.” He gave me very specific instructions that stemmed back to his time studying with Eddie Locke and Papa Jo Jones, and I will forever thank him for this. A recording featuring Kenny I want to reference is a Bill Charlap record called “All Through the Night.” On the title track, Kenny is playing such beautiful brushes. I later found out that he is using the “Counter-Clockwise” brush pattern. This pattern works really well, specifically with 2-feel songs, and gives a nice, thick coated sound to the music. On this same record, Kenny plays great ballads. He’d figured out a way to have a consistent sound and patterns to support the music.

The next ingredient I find that contributes to playing good brushes is posture. I remem- ber my first unofficial lesson with Lewis Nash where he invited me down to Right Track studio in NYC to check out a record date with a vocalist, Kenny Rankin. He invited me into the drum booth, and said “Sit down man, and check out my kit.” I remember sit- ting behind his kit. Above all what I remember was sitting down on his throne. It was spaced in a position where I felt like I was sitting at the kitchen table. The drums felt so comfortable, and I remember telling him, “Man, I feel like you on the kit.” What that meant was my back was arched and I immediately sat with correct posture on the drum kit and everything flowed so much easier. I find that so many of my favorite drummers have a great posture, and it’s very key to getting a consistent sound on the kit. The same is true with the brushes. Especially with seat height.

Playing and Learning on Stage

As a performer in the last few years, I have been really fortunate to work with a lot of great artists, but one of the most highly regarded musical associations I have had in the past was with The Christian McBride Trio, featuring Christian Sands on piano, and Christian on bass, the Joey Alexander Trio and now my quintet “Generation Y.”

On tour, McBride would come up with arrangements on the spot during sound-checks before gigs, and I remember every concert he always made a point to perform several songs where I would be featured on the brushes. I remember him saying to me one time, “Young cats don’t really know how to play brushes anymore, but you do.” So he started creating moments in the show to spotlight that part of my playing. As YouTube videos and recordings would surface around the world from our shows, I started get- ting emails and requests via social media asking me about my approach to the brush- es. Especially once the popular “Cherokee” video was released online, featuring Christ- ian McBride, Peter Martin and me in Slovakia, playing fast swing time, I, all of a sud- den, was being regarded as a young “Brush Guru!”

However, before that amazing stint with McBride, the brushes have been a major part of my arsenal with singers, and small gigs all over the world. I found myself on gigs where playing time with brushes was preferred because sonically it was more accept- able in terms of volume with most artists.

I also began to see other wonderful drummers performing live who, when they play brushes, inspire and scare me!

The first is Jeff Hamilton, whom I first started checking out when he would visit the East Coast and perform at Dizzy’s at Lincoln Center in NYC. The first time I really got a chance to study him was on a Jazz Cruise. He was playing there with his trio and Jeff is part of that last breed of drummers who are exceptional time keepers, great orchestrators, leaders, and showmen all rolled into one. I feel that drummers from the 1950s and before that really incorporated a high level of showmanship into their playing, and when you watch Jeff play the brushes, it’s like fireworks! I always take a page or two from each drummer that I admire to incorporate into my playing. From Jeff, I sought to work on great timekeeping, mastery, leadership and showmanship.

Lewis Nash is the Brush Wizard because his sheer virtuosity on the kit is incredible! He has the ability to not only be a showman, but he is a self-contained movie – you will literally experience things within his playing that you have never seen any other drum- mer perform or do again after him! When Lewis sat me down for a lesson, he taught me about articulation with the brushes– knowing which part of the brushes to emphasize to get a certain sounds with them. Lewis, helped me with develop my own innovations utilizing the brushes through articulation.

Before the pandemic, Kenny Washington would perform in Bill Charlap’s trio at The Village Vanguard for a two or three week residency and during those 75-80 minute sets, it would be quite beautiful watching that trio play in a timeless manner night after night. I often felt like I should have a tuxedo on watching and hearing them play because they possessed so much sophistication and class. My favorite part of the night with Kenny was when they would play an uptempo tune, which they performed at a soft dynamic level. Kenny, as a brush player, has the perfect balance of touch, assertiveness, and musicality and his knowledge of the tune is impeccable. From Kenny, I learn to sound like a jazz drummer. Kenny has the sound of jazz deeply etched into his brush and stick playing, and when I listen to him, as when I studied with him, it reminds me to keep my playing connected to the masters of this form. Keeping Art Taylor, Max Roach, Philly Joe, and many others within the scope of what I play in the music is not only part of the tradition, it’s in there because it works!

Joey Baron, like Lewis Nash, is another king of innovation! Joey Baron always leaves me walking away understanding something new about the drums and the brushes. I remember going to one of his gigs in NYC and I sat really far away from the kit, but I remember seeing him use these thin wooden rute like sticks. I approached him after- wards and asked, “Joey, what were you using man?” He said, these are Kebab Skew- ers.” HA! Sure enough I went to the grocery store, and there were Joey’s sticks right there on Aisle 5, lol! What this showed me was that Joey has no limits to what he will explore and try on the kit. His brush playing is forward moving, and traditional. He gets such a beautiful sound out of the drums that I seek to have beauty and exploration as part of my playing, thanks to Joey.

Herlin Riley – last, but certainly not least – is one of the most organic, and soulful drummers on the planet! I have always had a beautiful relationship with Herlin, first as a student, and later as a colleague, because he and I both would trade off the gig with Monty Alexander’s Trio. Herlin taught that the brushes have to feel good first and fore- most, and, quite frankly, he never cared how I got to that feeling or sound as long as I found it. I remember we would sit inside of the drum room at Juilliard where we would have two kits set up and, when I would ask a question, Herlin would just play the groove, or whatever I had questions about, and then ask, “Any other questions?” – lol! Naturally then, when we spoke about the brushes, Herlin began to just play them in front of me and I learned from watching and listening.

The Keys to Good Time

It’s taken me a long time to learn how to develop good swinging time because it’s so different than most of the other grooves that are created on the drum kit for one simple reason. The focal point of a swing groove is to push from the ride cymbal, or when us- ing the brushes, from my right brush/hand. This is very different than playing a funk or rock groove where the groove is built and sustained from the bottom up. In swing, the time comes from the top down.

When playing the brushes, the first key to the time feeling good is developing that “lead hand” technique playing the “Spang-a-Lang” pattern. The key is to really understand each rhythmic aspect of this groove, and I have spent many, many hours in the prac- tice room studying that pattern repetitively.

Then you have to work on the left hand and decide are you going to sweep with ac- cents, or no accents. Then the speed of sweeping, etc... it really requires a myopic and methodical approach with analysis on your playing to get better at playing good time with the brushes. Also, remember to not involve the hi-hat or bass drum until you can really get the hands to sound cohesive on their own.

Below, I list the key elements I have learned and developed in keeping good time, both with the brushes and on the kit in general, because it’s important to know that what you learn about how to swing applies to your brush technique as well.

6 Keys to Playing Good Time

1. General Listening

You have to learn how to hear the whole band, and the tune, in a perspective separate from your own playing. Most musicians spend a large part of their musical life never listening beyond their own playing. I always desire my playing to be informed by other musicians, which is why I prefer not to play alone, because everything I play is con- nected to someone else.

2. Listening to the Right Things at the Right Time

Many times, once musicians start to listen beyond their instrument, it becomes chal- lenging to choose what to listen to and when. As a drummer, when playing brushes or on the kit, it’s important to first listen to the bass player. We must lock in with them, and then connect to the piano, guitar or other present chordal instrument. From that point, I then listen to the horn player or singer but all of the other fundamental connections are still happening. Also, I monitor to my own dynamics as well and treat my ears like a fader board in the studio, constantly adjusting for the sake of the music.

3. Connecting with Other Musicians

You have to connect with the other musicians to play good time, otherwise, as the drummer, we can make or break the band and without that connection we will sabo- tage every performance.

4. Good Technique

Listening and connection are incredibly key, however there are non-musicians who are great listeners and connectors. You have to hone your technique to truly play good time, because if the technique isn’t solid, then what you hear, or desire to connect to musically will be impossible for you to truly achieve.

5. Learn the Repertoire

This is simple: Learn the music you are playing – and I prefer to memorize everything. If you are still developing your reading, like with Big Band charts, memorization helps if it still lacks that organic feeling.

6. Relaxing and Playing

My playing took a HUGE shift when I learned to relax, breathe, and not let anxiety into the room, onto the bandstand, or to sit along-side me on the kit. Relaxing, and just playing will account for most of the great times you will have in music, and that simply derives from having confidence.

As I come to the conclusion of this article, it’s important to have the right tools for the trade. I have taught drummers all over the world, and about 85% of them all had horrible brushes, and many of their technical challenges existed because they didn’t have the right tools. Please go and pick up a good set of brushes, and half the battle will have been won.

To clarify, I am referring to either a pair of wire, telescopic brushes, or any pair that does not prohibit your ability to execute properly the patterns and the music. I prefer the Promark TB3 model or the Regal Tip Classic Brush which was created by Joe Calato who holds the first patent for the retractable brush.

The Sound of Jazz

I mentioned my college studies with Kenny Washington, who is a renowned historical authority on Bebop drum history and with just a few adjustments to my brush tech- nique, he increased my sound on the brushes immediately, which in turn allowed me to play with more confidence. Studying with Kenny was pretty transformational because he was what you would call “old school” in his approach, and didn’t mince words. Kenny’s approach was very much, “It’s my way or the highway.” This was not in arro- gance, but more about: if this is what you want to learn, this is the jazz tradition and

valued Kenny’s approach greatly, because it made everything way more realistic – not to mention, to hear someone say, “Papa Jo showed me this, and now I am showing you,” was incredibly deep and meaningful to me. To my mind,

jazz music is never more effective than when it is passed down as an oral tradition from the master to the student.

Wynton Marsalis, often says that people will often reject what is difficult. I believe the majority of young drummers don’t play brushes because they seem quite difficult so I want each of you that read this article to buy a pair of brushes, listen to a great record, and find your connection with the brushes. Don’t be afraid. It’s right there waiting for you!

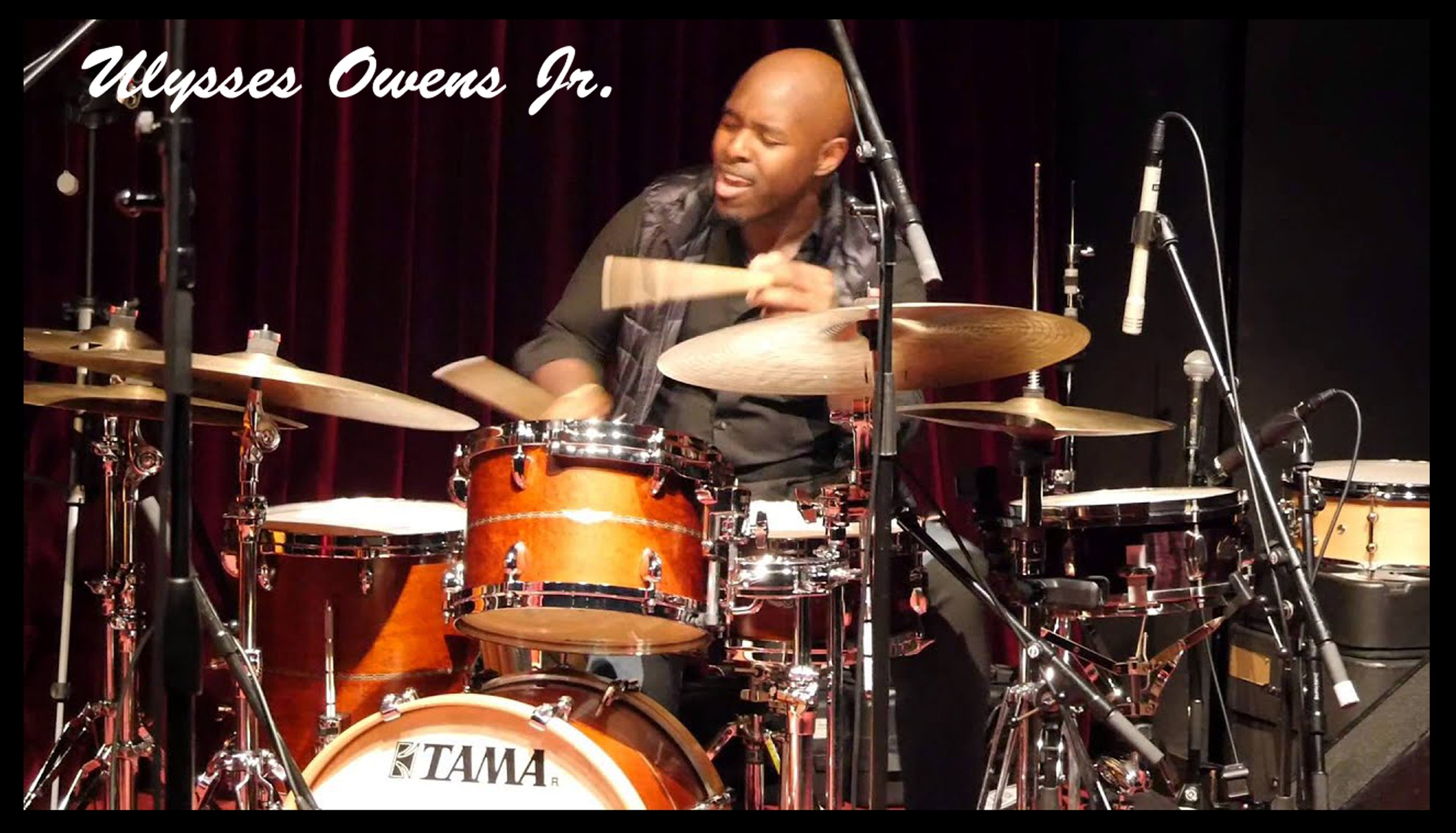

Writer Biography

Three time GrammyTM Award-Winning Drummer Ulysses Owens Jr., known for being a drummer who (The New York Times) has said “take[s] a back seat to no one,” and “a musician who balances excitement gracefully and shines with innovation.”

Performer, producer and educator Ulysses Owens Jr. goes the limit in the jazz world and beyond; claiming eight successful albums of his own. Owens has also gained spe- cial attention for his performances on GRAMMY Award-winning albums by Kurt Elling and The Christian McBride Big Band . In addition to five GRAMMY Award Nominated albums with Joey Alexander, Christian McBride Trio, John Beasley’s Monk’estra, and Gregory Porter.

Both Jazziz and Rolling Stone Magazines picked his album “Songs of Freedom,” as a Top Ten Album for 2019 and in 2021; his most recent Big Band release, “Soul Conver- sations,” was voted the top album in May 2021 by JazzIz Magazine. “Soul Conversa- tions,” received rave reviews and was added to multiple playlists on Apple Music, Spoti- fy, and Sirius XM; and now the band is touring nationally. The Ulysses Owens Jr. Big Band has also been voted “Rising Star Big Band ” of 2022 by Downbeat Magazine.

His upcoming eighth album release A New Beat, will feature his new “Generation Y” Band on the Cellar Jazz record label. The album was produced by Jeremy Pelt and recorded at the legendary Rudy Van Gelder Studios, in New Jersey.

As an author Ulysses has published two books titled: Jazz Brushes for the Modern Drummer: An Essential Guide to the Art of Keeping Time, and “The Musicians Career Guide: Turning Your Talent into Sustained Success, distributed by Simon and Schuster. His third book, Jazz Big Band for the Modern Drummer: The Essential Guide to the Large Ensemble, for Hal Leonard Publications was released January, 2024, and award- ed the “Editors Choice Award,” by Music Inc Magazine. He is also a regular contributing writer for the WJCT Jacksonville Music Experience, Downbeat Magazine, Jazz Times Magazine, Percussive Arts Journal, and an Op- Ed contributor the Florida Times Union Newspaper.

As an educator Ulysses has been part the jazz faculty at The Juilliard School as Small Ensemble Director for over seven years ; served on the EDIB (Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, and Belonging) committee. He has also served on multiple panels, and taught var- ious workshops within the Alan D. Marks Entrepreneurship division. He is also the Artistic Director for his family’s arts non-profit organization in Jacksonville, Florida called “Don’t Miss A Beat,” and the newly appointed Artistic Director for the Friday Musicale Summer Jazz Camp in Jacksonville Florida. He has a three-year appointment as the Educational Artist in Residence for SF Performances in San Francisco, CA. He has also recently been asked to join the Drumeo Online Educational Platform as their Inaugural Jazz Drum Instructor and is developing the curriculum for his interactive course, “30 Day Jazz Drummer,” that will launch in June, 2024.

In 2024 Ulysses is venturing into Radio with his co-host Keanna Faircloth who is a celebrated anchor in Jazz Radio with shows on NPR, WBGO; and now with Ulysses they have created “Jazz Beyond Tradition” for Jacksonville Music Experience on WJCT Public Radio. The show will air in April 2024 and features an exploration of Jazz Voices with engaging interviews; highlighting the artists inspiration, and process for their WJF performance.

Ulysses remains consistently in demand for new projects, and consulting opportunities,; remaining one of the most sought-after thought-leaders of his generation. Yet what matters to him consistently is giving back and continuing to be grateful for a new day to make a difference in the lives of others.

Ulysses received his Bachelor Fine Arts from The Juilliard School in 2006 and was the 1st African American Jazz Drummer to be admitted to their Inaugural Jazz Program in 2001.