Introduction and transcription by Bob Campbell

Photos by Jim Catalano and Bob Campbell

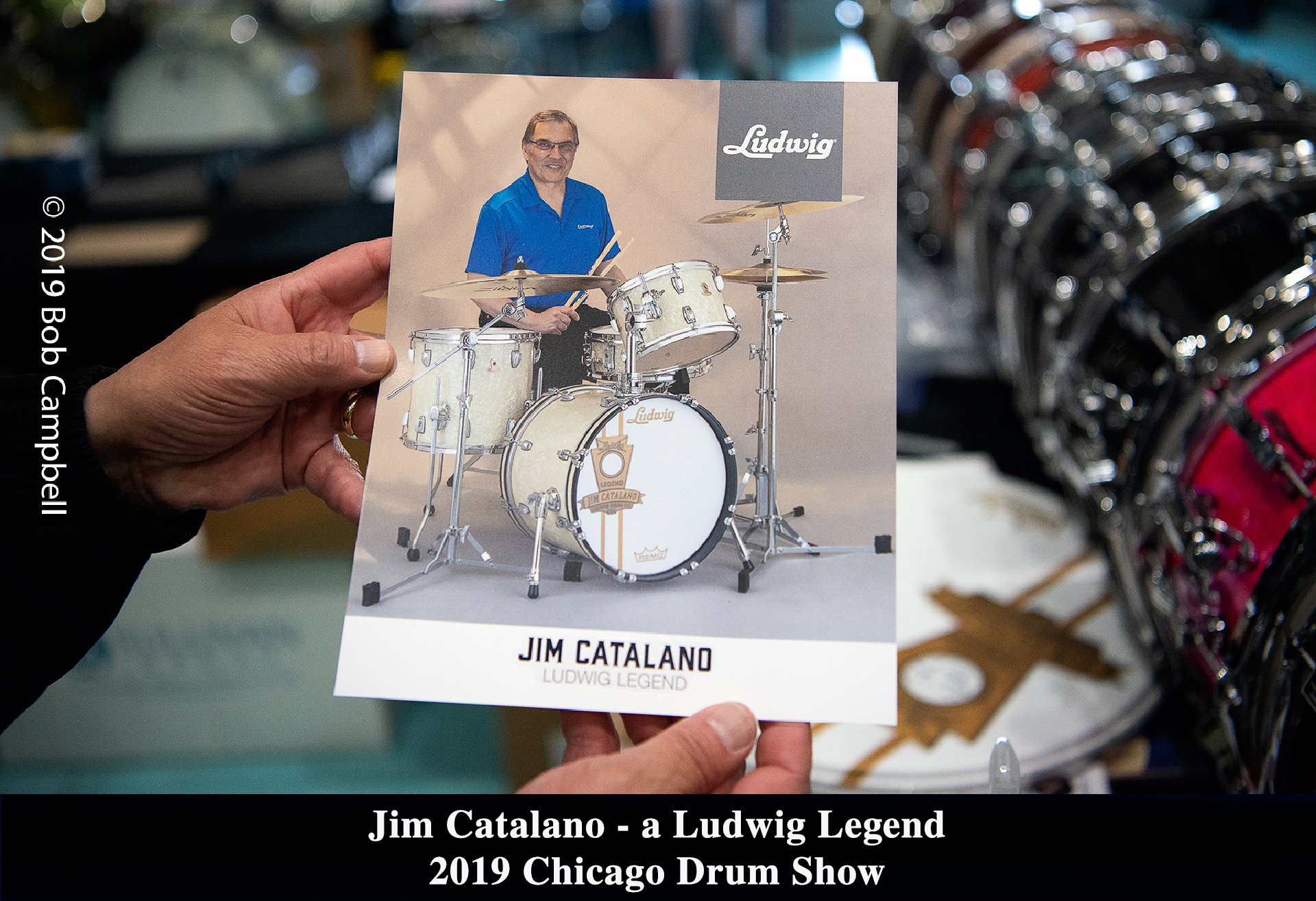

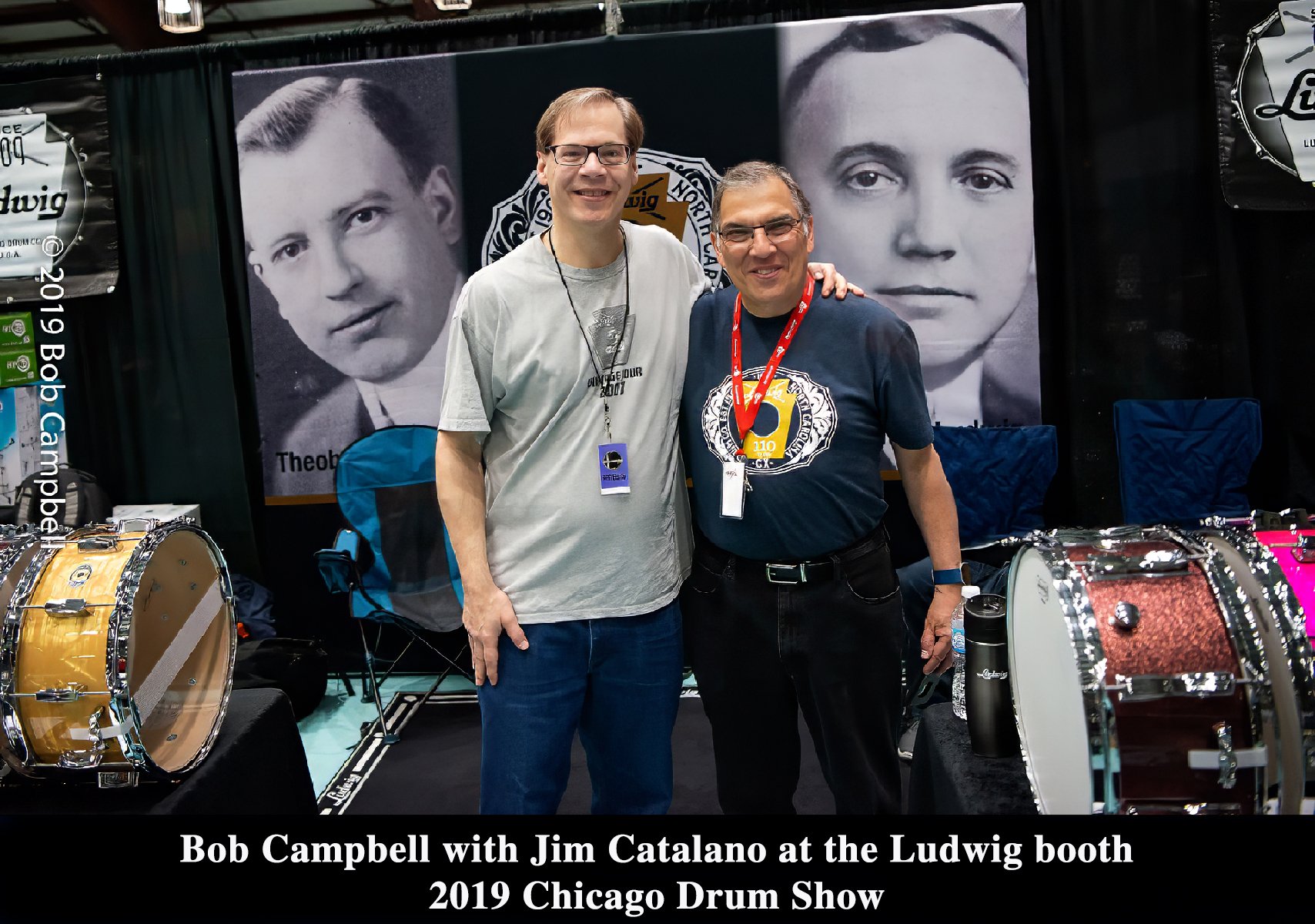

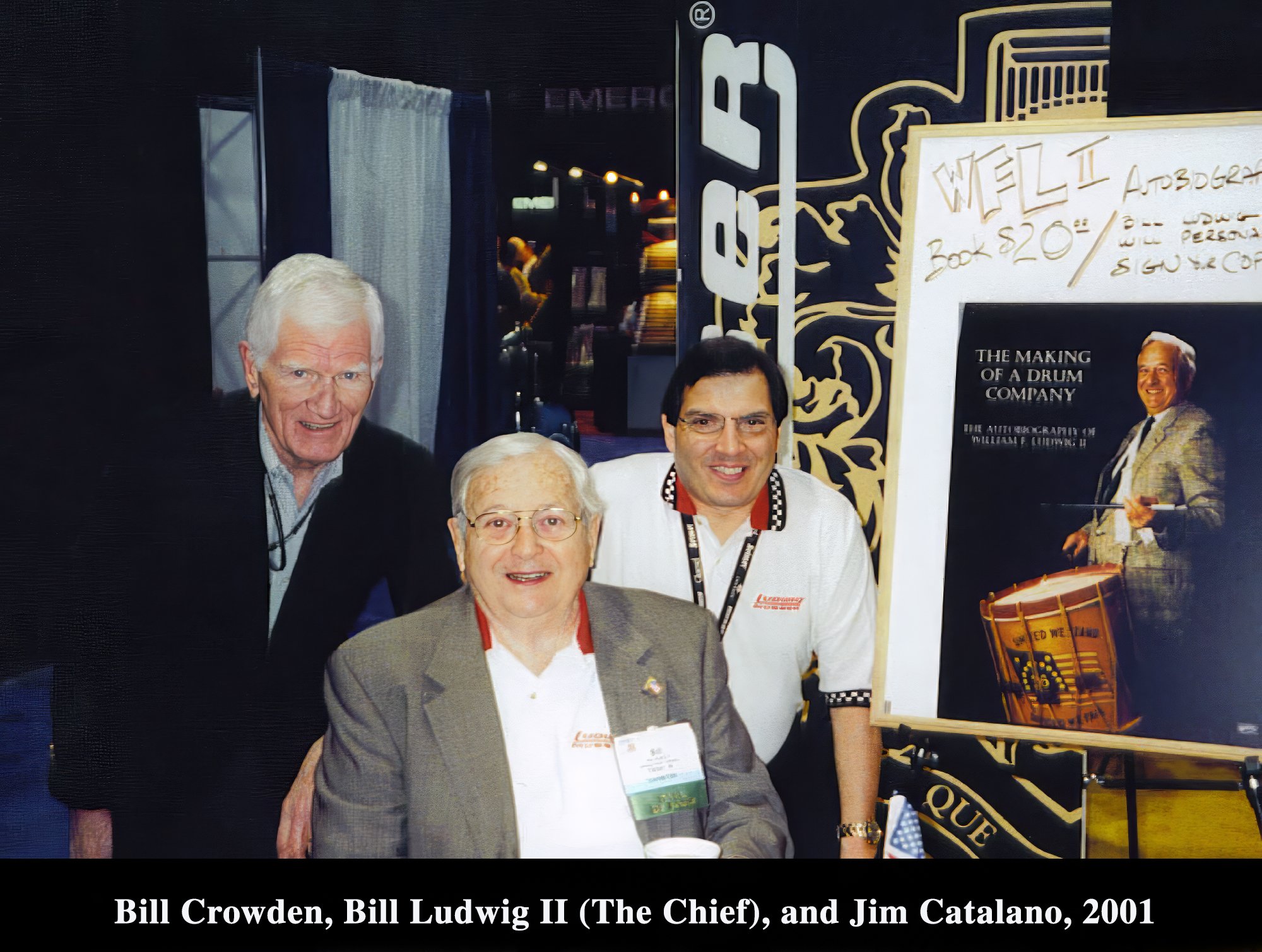

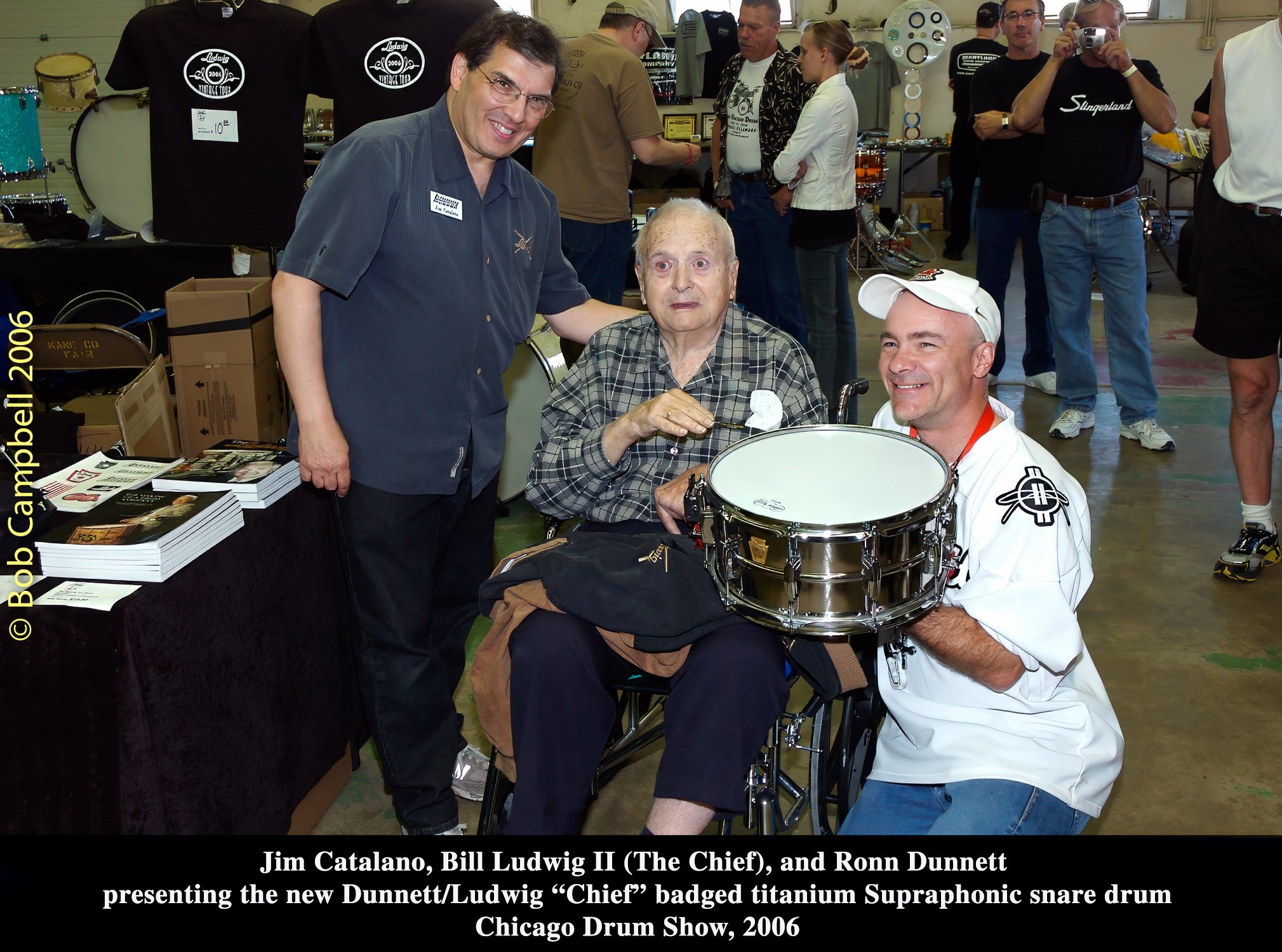

I first met Jim Catalano over 20 years ago at the Chicago Drum Show when he was manning the Ludwig booth as the Marketing Manager. I was immediately impressed by his warm smile, passion for drums, extensive knowledge of Ludwig drum history, and his graciousness in answering questions from show attendees, even the most naïve drum questions (including some from me at the time!). He seemed like a natural born teacher as he loved to share his knowledge and instill excitement about drums and drumming. I never got the chance to know Bill Ludwig II, so to me, Jim was the face of Ludwig. He represented the brand with positivity, integrity, knowledge, and immense respect for the company which the Ludwig family had built. I learned a great deal from Jim over the years and enjoyed every conversation about his wonderful experiences working at Ludwig. In 2019, Jim announced that he would be retiring from Ludwig after 36 years of service. This was certainly well deserved but we all knew he would be greatly missed.

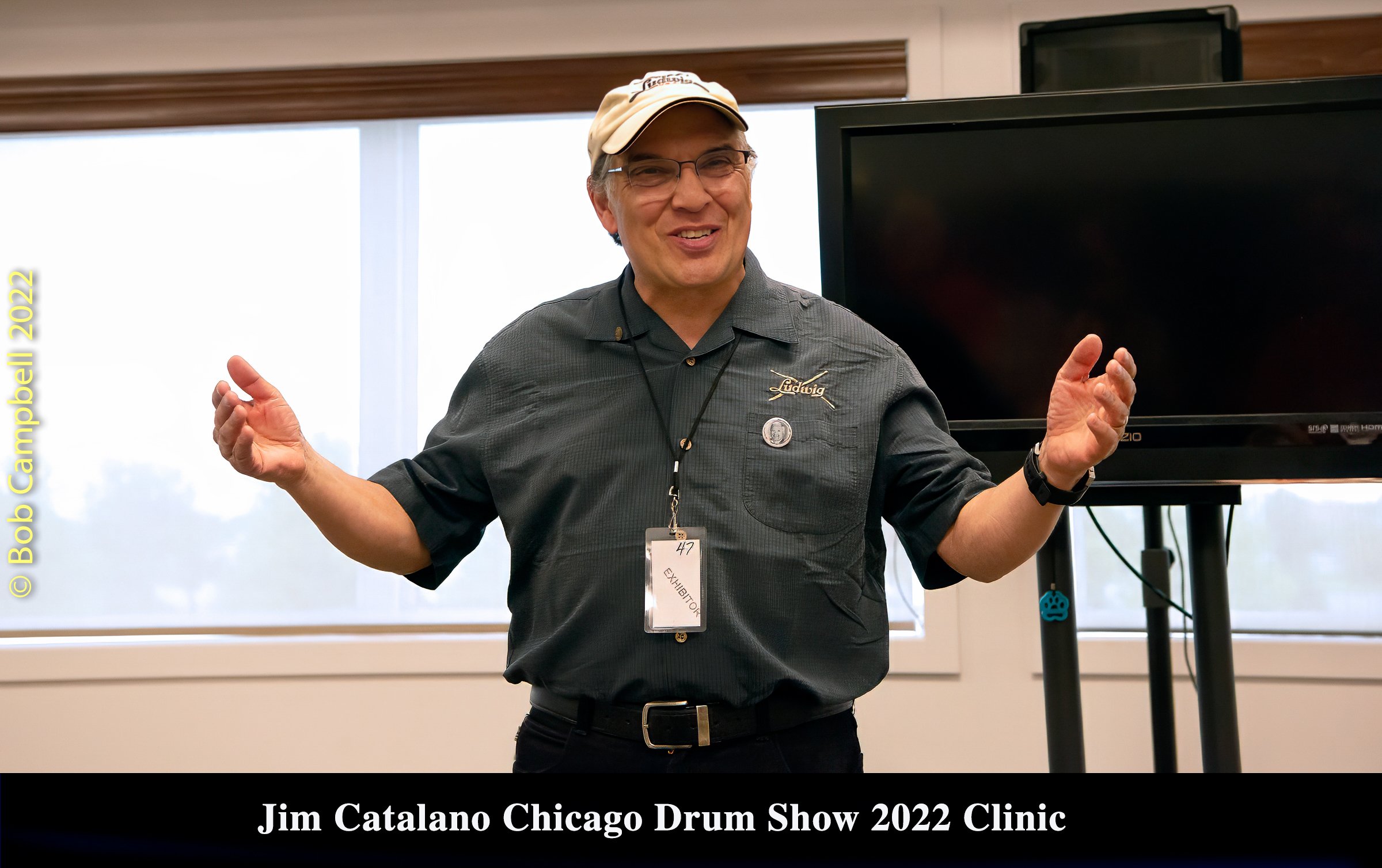

Three years later, Jim delighted a packed audience at the 2022 Chicago Drum Show by giving a clinic sharing his personal experiences throughout almost 4 decades in the drum business. I have transcribed Jim’s clinic below for those who were not able to attend and hope you will enjoy Jim’s wonderful anecdotes and shared life lessons.

Jim Catalano:

In the beginning, there were drums, I mean trumpet:

“Growing up, my backyard in Pennsylvania was the high school parking lot. A drum corps would practice there. When I was five years old, I was absolutely captivated by the sound of this drum corps, but not of the drums. I was captivated by the brass. So, when it was time to pick an instrument, what did I pick? Trumpet. I wanted to be a trumpet player. In fourth grade, that's how I started off - as a trumpet player. I kept getting better and better, but I also started getting nosebleeds. The music teacher called me in one day and said, “Jim, you're going to have to come up with another instrument.” This was around early November 1963.

We all know what happened on November 22, 1963 - the assassination of our President. It shocked the world, but it devastated this 10-year-old boy in a massive way. To me, it was like the first family member to die. Later, on February 9, 1964, I got out of my depression, because that's when the Beatles played on The Ed Sullivan TV Show. That was the night I decided I wanted to be a drummer. And so, I had to tell my mom and dad, “You know, you bought me a trumpet and everything, and I'm taking trumpet lessons, and I'm playing trumpet in elementary school band, but you know, I got these nosebleeds… This gave me a great excuse to get out of trumpet playing to be a drummer. And that's how I got into the whole drum thing.”

Discovering Tony Williams and a true passion for drums:

“I was really lucky as a kid, in that there was a gentleman named Cootie Harris. Now, by the way, if your name's Cootie, you're going to be a drummer, and you know, you're going to be a jazz drummer, right? I mean, you know, you can't avoid it if your name is Cootie. My dad found this African American gentleman who had just returned from New York City, playing with some of the greats. Cootie Harris wasn't the drummer for Coltrane, but he knew them, and he was in those circles. He came to my small town to kind of settle down from the jazz era of 1965. I was so fortunate to start studying with him. One day he told me, “I want you to listen to something. This is Miles Davis.” So, we started listening to Miles Davis, and he said, “You know, the drummer with Miles Davis is named Tony Williams. “Man, he is absolutely great,” I stated. You know, he's only 17 years old.” And I'm, what, maybe 12 or 13? It suddenly dawned on me that Tony was not much older than me, and there is this player that can do this. It excited me in such a way that I decided definitely that I was going to be a drummer, and I wanted to do this forever.

When I was in ninth grade in Pennsylvania, we had what was called district band, but it was a junior high district band. While I was there, there was this guy who was the guest band director/conductor. His name was Daniel Dicico. After one of the rehearsals for a district band concert, he said, “Jim, you're going to be in the marching band next year when you go to high school.” And I said, “Well, I think so.” I bet you love football he said to me, like the Nittany Lions, Penn State. I said, “Well, they're okay. But I'm a Notre Dame guy.” You never know. You say one word, one association to one person, and that can change your life. A couple years later when I was a sophomore at HS district band or regional band, I saw Dr. Dicico again and he remembered me as being a Notre Dame fan. The rest of my high school years I would see Dr. Dicico at Regional band and All-State Band in Pennsylvania and he always would say “Hey, Notre Dame, you’re Notre Dame. Yeah, you remember me?” He said, “I'll never forget.” “

The college years:

“So, what's so cool is that I decided to go to college to major in music. Guess where I go? I go to the very college where Daniel Dicico was the band director. I had no idea he was the band director. It was called Indiana University of Pennsylvania. Before I graduated in 1975, he calls me up. I'm student-teaching in Pittsburgh. He says, “Jim, you're not going to believe it. There's a graduate assistant band director teaching position at Notre Dame for two years with a full-ride scholarship. I'm supposed to post it on my board for everybody. I'm not. I'm just telling you about it.” So, I applied, and I got in. That's important for me, because as a result of Notre Dame, I went to South Bend, Indiana, where Notre Dame is, and South Bend is only 25 miles away from a town called Elkhart, which was the band instrument capital of the world.”

Early teaching experience:

“I graduated from Notre Dame in 1977 and became a high school and middle school band director. Frankly, I was a decent middle school band director, but a pretty inexperienced high school band director. I was too young and immature. I weighed like 120 pounds. You can imagine the kids looked older than I did. It did not go as well as I had hoped, but I thought it was awesome. At the middle school level, I was bigger than the kids. And that was good for me. The first show I went to as an educator was this Midwest band and orchestra convention. So I go through the booths, and I meet different people. I went into the Selmer Company booth and started talking to people, that’s where I met a guy named Jim Coffin. Now, some people may not know who that is, but Jim Coffin went on to be pretty big-time in the music industry. I developed an acquaintance with him over time. It was kind of cool.”

An unexpected career change:

“Fast forward to 1978, and Jim Coffin calls me up and he says, “Jim, what are you doing in the summertime in between teaching?” I said, “Well, I'm going to be a playground director.” And he said, “Well, I have another idea for you. How would you like to work part-time in the music industry with me at Premier Drums?” I said, “I don't know anything about business.” So, I went to work part-time for the Premier Drum Company in the summer of 1978. As a result of that, I started making connections. When it was time for me to go back to teaching, they said, “Jim, how'd you like to stay?” So, I did. For three years, I stayed as the Product Coordinator for Premier Drums working with Jim Coffin. He was a great boss. He was funny, always had a joke every morning to start your day off. It was really a wonderful experience. He was fair and honest.

Then, I got a chance to go to work for a company called C.G. Conn, as the advertising manager for Conn band instruments. Artley and Armstrong were some of the brands, but Conn also owned a drum company called Slingerland and Deagan Mallet Instruments. I did that for two years, from 1981 to 1983. You never know how things will go. Because I had worked for those three years at Premier and now 2 years at Slingerland, I developed a good reputation in business.”

Bill Ludwig sells the Ludwig Drum Company to Selmer, a time of transition and hardship:

“I remember, on November 1, 1981, that's when a cataclysmic change happened with the drum industry. That was the day that Bill Ludwig decided to sell Ludwig drums to the Selmer Company, which was in Elkhart, IN. You probably wonder, why did they sell to the Selmer Company? Well, the answer was part of the history of the music industry. Remember that Ludwig was a company started in 1909 by William F. Ludwig Sr. and his brother Theobald, who passed away in 1918. But during the Great Depression, they could no longer sustain the business. Silent movies in the 20’s came in which wiped out a lot of drummers’ jobs. They eventually sold the company to C.G. Conn, the band instrument company in Elkhart, Indiana, who also at that time owned Leedy. Essentially, Bill felt that the Selmer company had the financial resources, stability and reputation in the music industry to carry the Ludwig Drum Company forward.

Unfortunately, there are negative things that can happen when other companies acquire other companies. One of the first things that they do is start thinking, “We don't need this person. We don't need that person, and they start lopping off people. Unfortunately, they lopped off engineering and marketing people, and people that were really important. Those people had not just the knowledge of the percussion industry, but the connections and relationships with the industry too. Well, as a result of that, I think they took it too far. They let go so many people that they actually had to hire another person to run their marketing for them. And so, they thought of me.

Now, I was young, but I was pretty cheap, too. I was only 29 years old. I knew their system and they felt they could start a new version of Ludwig with me in that role. They brought me in, and put me in a, let's say, position of responsibility with the Ludwig Drum Company. Honestly, it was a scary experience for me. Do you ever have something good happen that you don't feel worthy about? That's exactly the way I felt. I'm going into this new job as Marketing Manager for Ludwig excited, happy that I have this opportunity, but not feeling ready for it. It was a big company and sort of number one at the time. Selmer took a young guy who had five years of experience and put him in this position of responsibility - it was awesome.”

Welcome to corporate life:

“But what also happened was, once again, uncomfortable conversations like, “Well, Jim, now that you're here, we don't need this this person or that person.” Frankly, I felt kind of screwed, if you catch my drift. All of these people that I needed to help train me to understand what was going on; now they were gone. I had this whirlwind kind of feeling about what was happening. So, in 1983 when I joined the company, all these things are happening day after day. And of course, you know, I needed to go up to the Ludwig factory and meet the people. Well, the Selmer people were “suit people”. You know what I mean by that? In that era, they're dressed in three-piece suits. So, I was forced to be a three-piece suit person.

Can you imagine taking this young guy, putting him in a three-piece suit to go up to the factory? Most of the factory workers disliked the people from Selmer anyways, because of all the changes that occurred. Now here comes a young whippersnapper, who's the new marketing person. It was not fun at all. One of my good friends now, Chuck Heuck, said, “You know, Jim, everybody hated you. Big time. Without you even saying a word or knowing who you were, but because you were from Selmer. Because you were the new guy, we all hated you. We were just waiting for the opportunity to take you out back behind the building to beat the crap out of you.” That was pretty much the way it was. Imagine now you have the corporate pressure of doing the business yet starting up not feeling worthy of having the job. Then you have the colleagues that you're supposed to lead not liking you very much.

I first started the journey of pulling everything together, trying to learn to be the good corporate guy that could bring the business together, and build up my own self as a leader. I had a significant role to fill and needed to develop the confidence that I could do it. I was also trying to make friends not falsely or pretentiously, and they needed to know who I was as a person. I was just a guy that was happy to have a job, any job. But I was also a drummer. I was a person that had a Master's degree in percussion from Notre Dame. I played timpani, marimba, vibes, and hand percussion. That's how I got into the business. It was a long building process to gain credibility.”

Bill Ludwig and The Test:

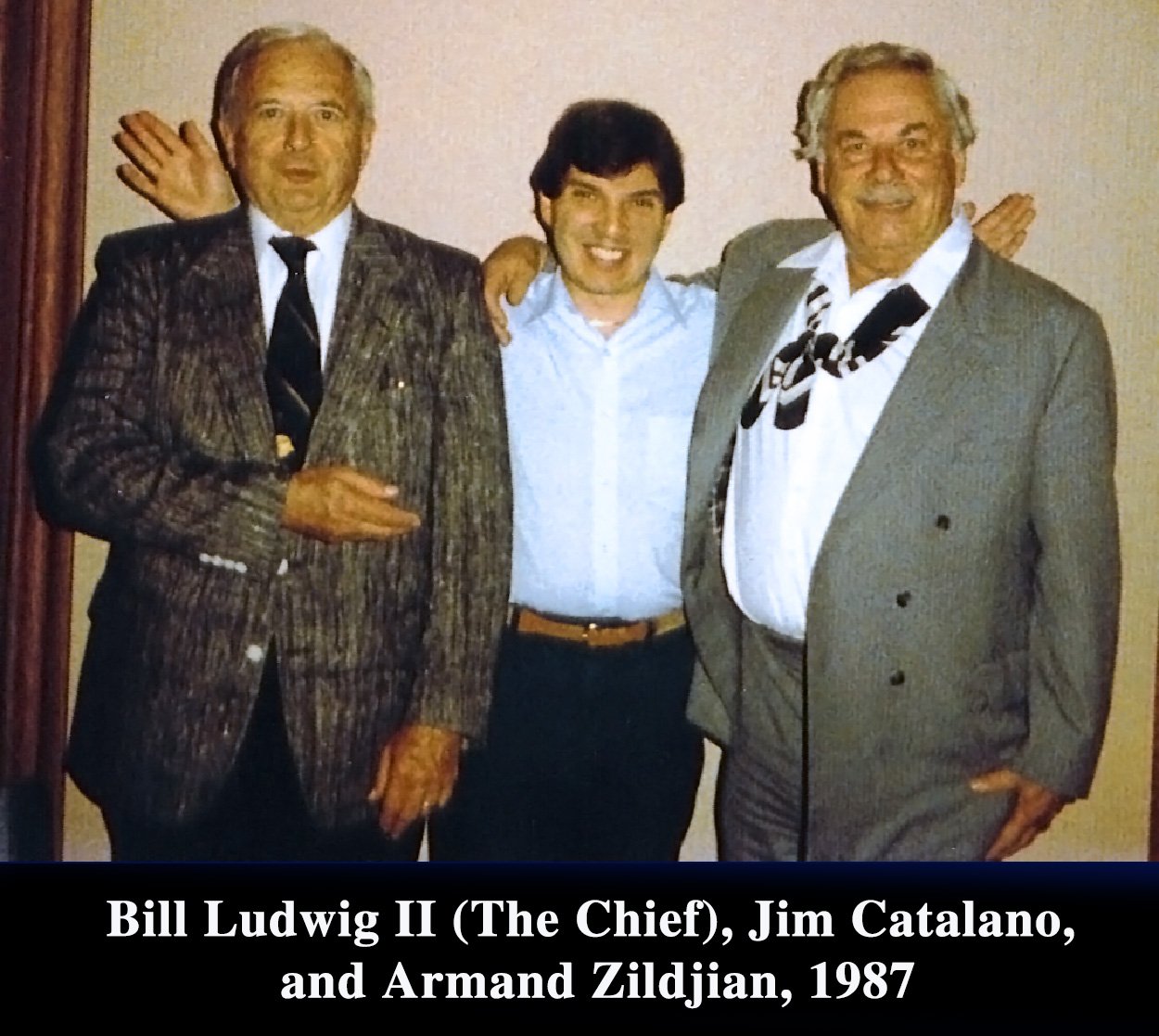

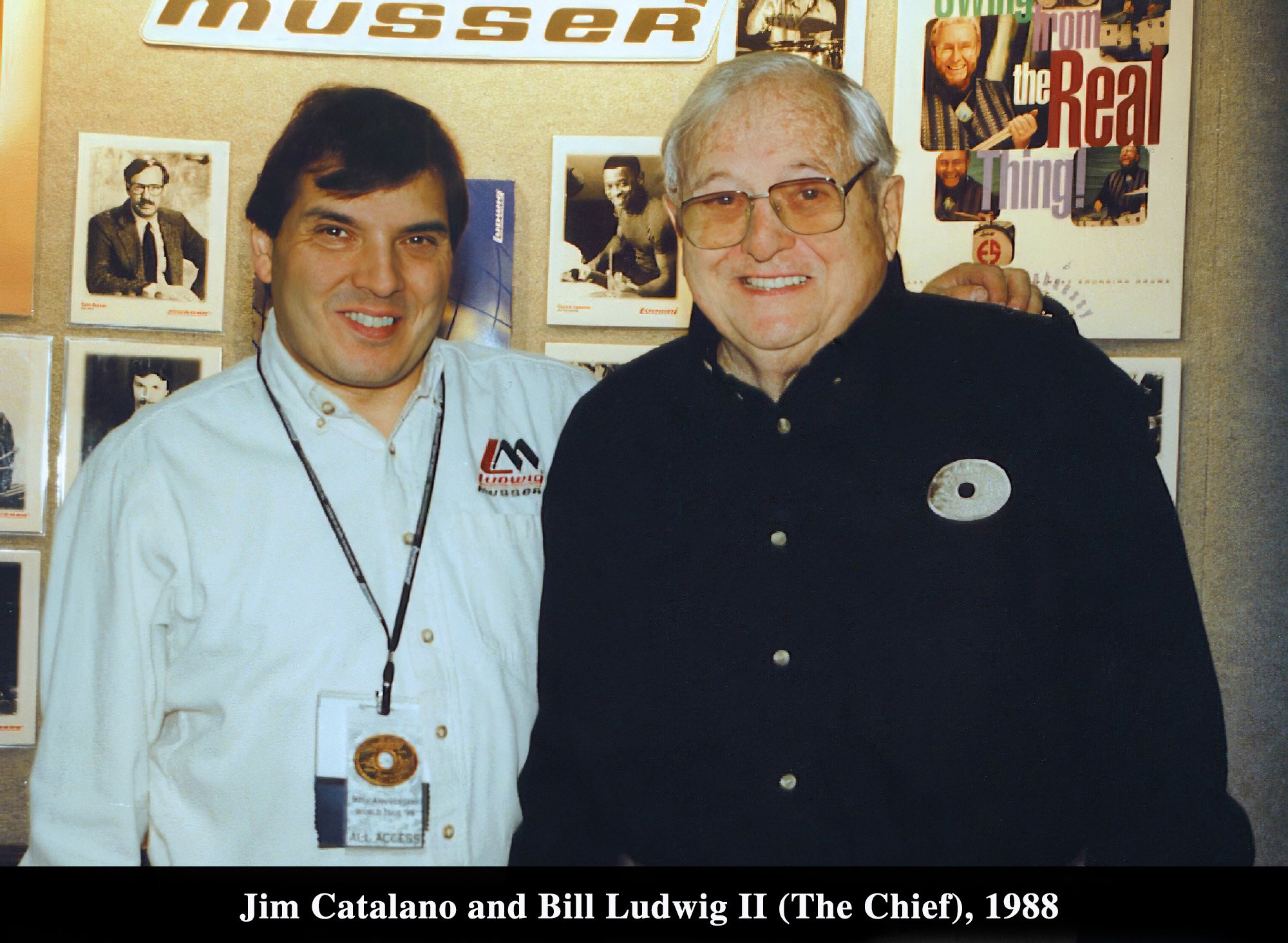

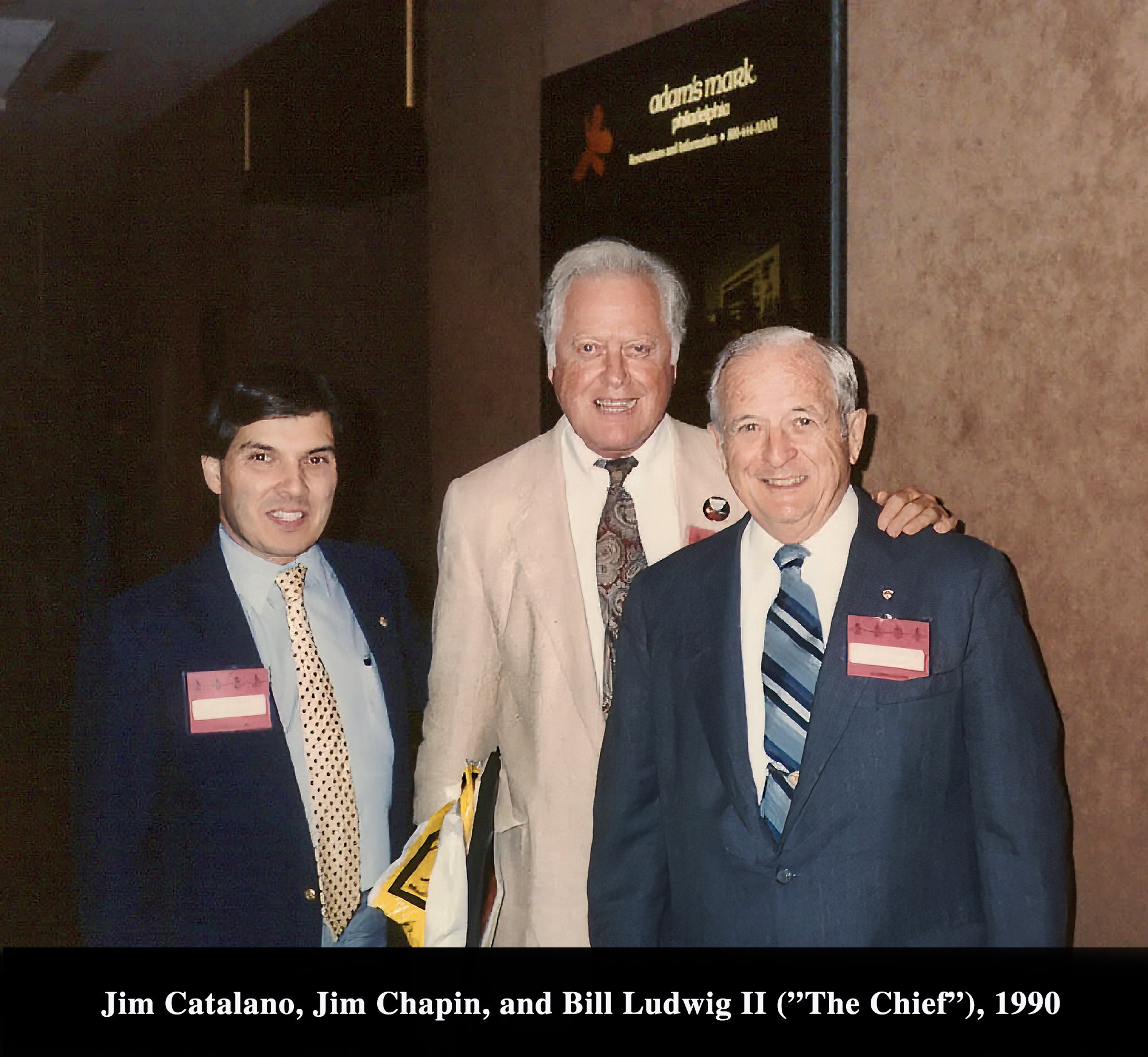

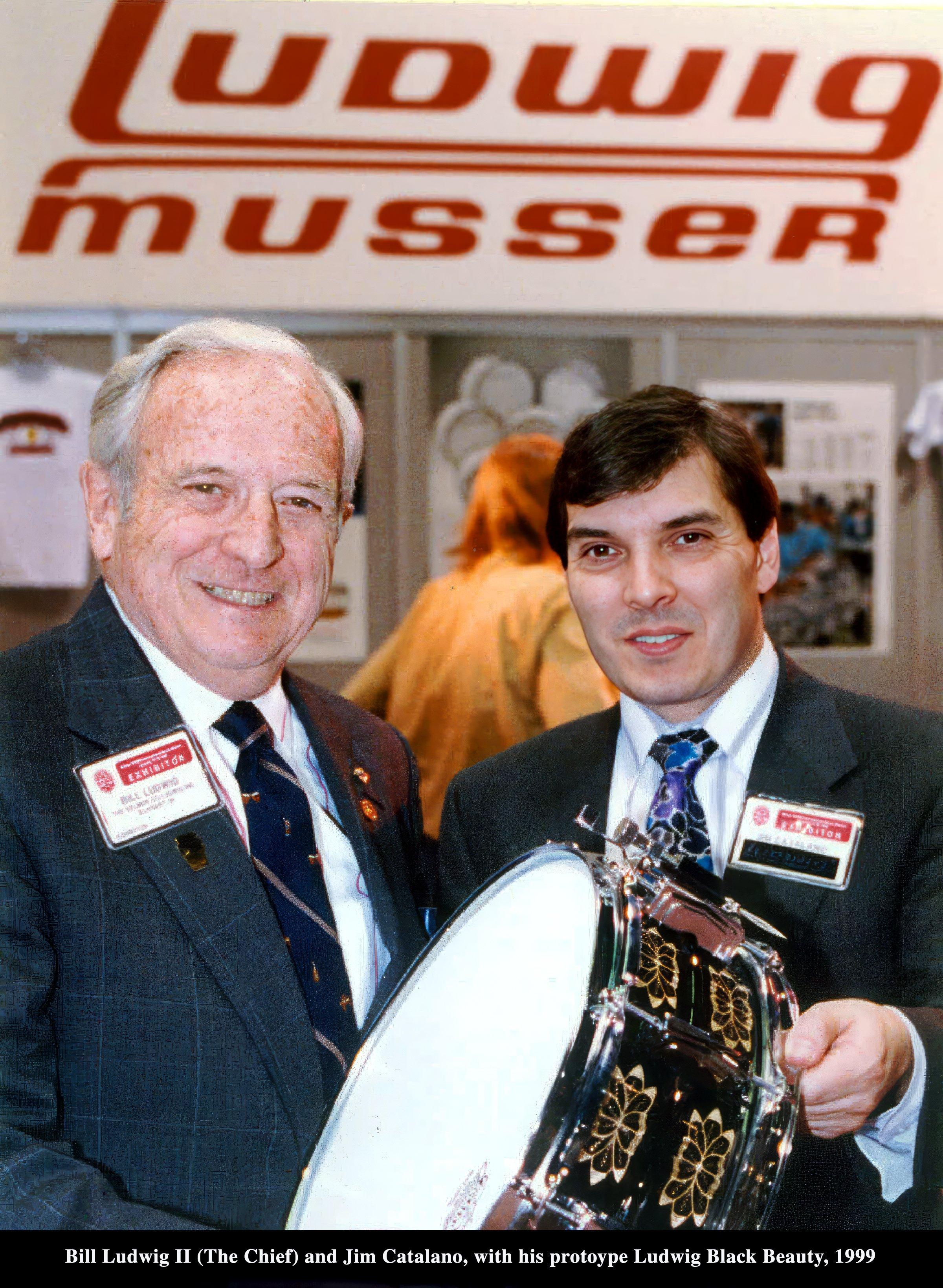

“Then came my visit to Bill Ludwig. He knew me a little bit because I had gone to shows in those previous five years. Early in my tenure at Ludwig I went to Bill Ludwig's house in Oak Brook, IL. It was a big house, and when I met Bill Ludwig there for the first time, he said, “Jimmy, welcome to the house that Ringo built.” Now, those are his exact words. So, Bill then says, “Jim, let's go on down to my drum room.” His basement walked out into a big open space. He said, “This is my collection. These are all my drums and percussion.” He went on to tell me about each one. Bill Ludwig was a brilliant guy. He goes over to a 12 x 15-inch marching drum with sticks on it. He picks up the sticks, and he starts playing Three Camps. While he's playing the first camp, he's motioning to me. I go over, now it's time for camp two. He needed to know that I knew that it. We went on, then played camp three, and played it all out. From there, he went right into the Downfall of Paris. But you know, there's a specific sticking to the Downfall of Paris. Bill wanted to make sure I knew what I was doing. I was getting “the test” from Bill Ludwig, just to find out if I was a real drummer. I passed! “

Origin of Bill Ludwig’s nickname, “The Chief”:

“We got along super well. We all call Bill Ludwig, “The Chief”. How that got started was really kind of simple for me. He kept saying to me, “You keep calling me Mr. Ludwig; stop doing that. My name is Bill. Now, I'm retired I no longer own the company. Just call me Bill.” I just couldn't do that. I was thinking, and for some reason something just popped into my head. I remembered Jane Hathaway from the Beverly Hillbillies, called Mr. Drysdale the Chief. It just dawned on me, so I said, “You know, Mr. Ludwig, can I call you Chief?” And he said, “I like that.”

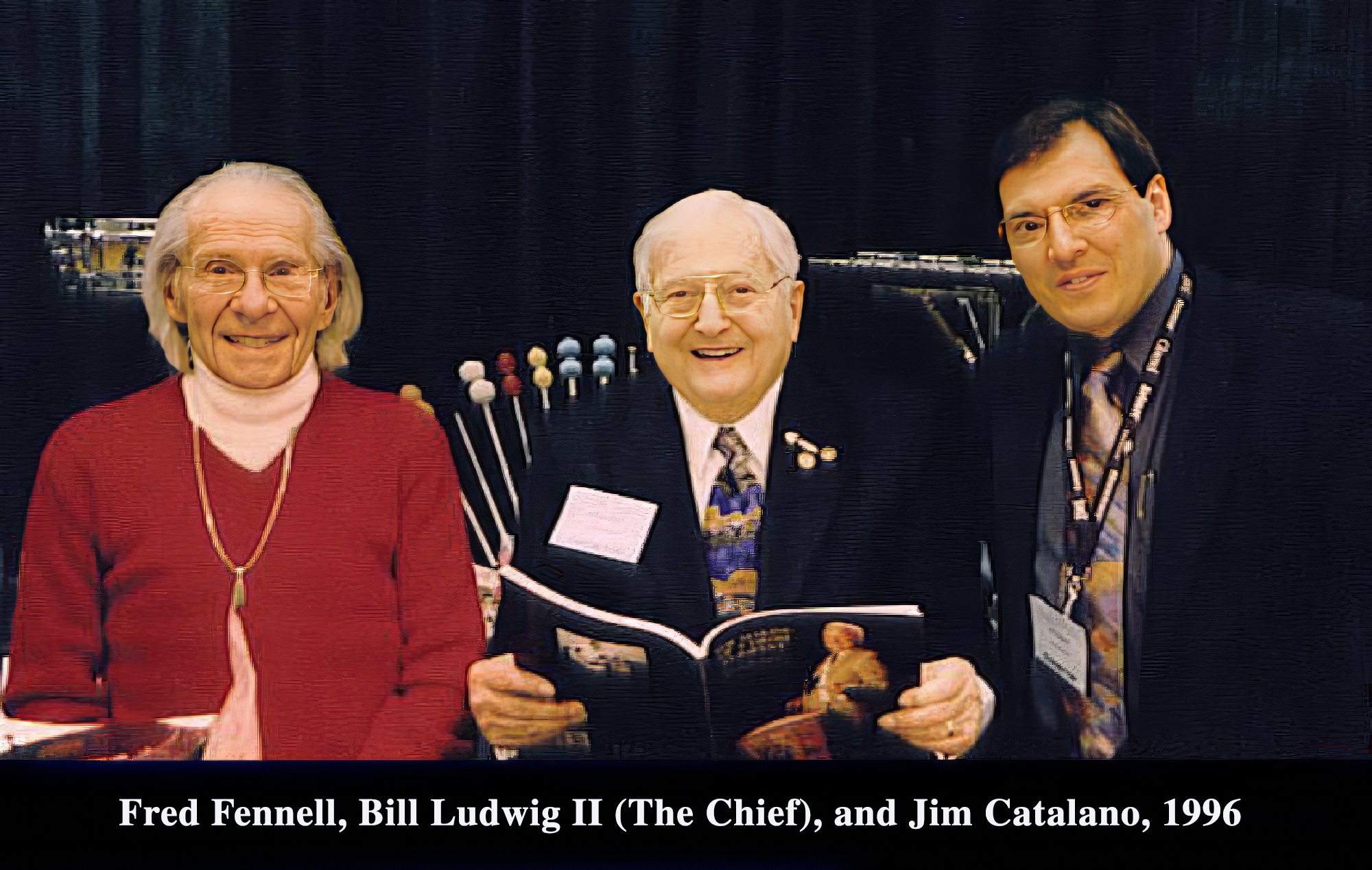

You know, having Bill Ludwig as your guide, and accepting you, it's a really big deal. Because now when we were traveling, if you're in with Bill Ludwig, you're in with the dealers, the artists, the drum corps, or wherever. Over time, we developed a kind of bonded relationship. I became almost like a family member, but let's say more like a “business son”, because he knew that I had similar interests that he had in drumming, mallet playing, timpani, Civil War era, drum information and history. So, we got to the point where we just became really bonded in all these types of things.”

Some thoughts on success:

“Woody Allen had a saying about success. He said, “80% of success is simply showing up. The other 20% of success is don't be a jerk; be a nice guy.” You know, be cooperative. If you can do those things, you're probably going to be okay. I think that was the story behind my success with Ludwig.

But if you worked, say, at a new company, you know with the younger companies, it's sort of like, the one thing you don't have to worry about is legacy, or the history of what the product looked like, or was supposed to look like. You can sort of develop your own new things, new ideas, new engineering, new shapes, new designs, and you're good to go. You try to do that with Ludwig, and you've got a problem. You can't just develop everything new. Therefore, you always have to be thinking of the past, as you're thinking of the future.”

Working with a company owned by a management company is challenging:

“Think about maybe the last time that trumpet changed its shape. How about maybe the last time the violin changed its shape? So, when you're working for a management company, the mindset is, “What are we going to change, a drum is a drum. There was always this challenge of keeping the past with you, as you're planning to move to the future, but not getting too far away. At the same time, you need to get the company’s support to build new things and have the engineers and the innovation that is happening. That was a challenging area. And that was an area that Ludwig didn't advance that much in many of those years. It was very simple. Number one, we didn't have the people; number two we didn't have the money or the resources to do it. So, what do you do? Well, you change things that don't cost a lot of money. You go back, and you start doing things that you did in the past. That doesn't cost a lot of money to reinvent, and you keep the brand alive and grow.”

Reflections on the passage of time:

“I worked at Ludwig from 1983 until 2019. What's cool about that is that it’s 36 years. When I retired, I didn't realize until I was at the end of my career, that I thought about it - you do the math - that back then it was in the 110th anniversary of Ludwig and you divide that by three, and you come up with 36 years. Okay? It's kind of a cool thing to know that I had to survive, succeeded, and have been part of a legacy brand for a third of its existence.”

The Ludwig “key” to success:

“So, what's important about that? My story was one day in 1986; It was at the Midwest Band Clinic. Bill Ludwig said, “I want to go to dinner with you. Just you and me.” This was rare, because Bill Ludwig is a party guy; he wanted to be in a big group with lots of people, lots of laughter, and lots of carrying on. I was only with the company three years, and he thanked me for helping to keep the Ludwig legacy alive, and for being a kind of an ambassador to fight against corporate stuff. In other words, to try to make sure that I kept us a family drum company, even though technically we weren't really a family drum company anymore. And he said, “You know what this drum key represents? This is the key to the Ludwig legacy.” I said, “Wow, that key? No, no, not that key.” “That’s just a key I had my in pocket” the Chief said. So, I thought about it and said, I get it. It's symbolic.” Bill said, “That's right. My father gave me this key to take forward. I'm giving this key to you right now. I want you to run with this for another 30 years.” One of the proudest things that I can say in my career is following that idea. Okay, through a lot of trial and tribulation. We all have trials and tribulations and everything we do. People have said, “Jim, why were you so loyal?” This is why - because something very important was given to me and entrusted to me by Bill Ludwig. You know, I felt this made me feel like part of the Ludwig family with a legacy to carry forward. I like telling that story simply because it was more than just a job working for a brand. It was something very personal to me.

It was one of the coolest moments in my life when Bill Ludwig passed that key to me. I had the distinct honor to pass that drum key on to Uli Salazar, who is leading Ludwig going forward. He’s leading Ludwig right now in the marketing area and he's one of my best friends. To me, that's an important thing - all part of the lineage and the legacy. There are not a lot of companies that have that - a sense of legacy.”

Another enduring gift from Bill Ludwig:

“When we started working back in the 70’s and 80’s, anytime on business you were not caught dead without a suit and a tie. Bill Ludwig, until the last 10 years or so of his career, always wore a suit and tie. So, he would have this Ludwig Tie Clasp on his tie. One of the things that was so special about Bill Ludwig was one time when I was working at a trade show with him, and said, he would put his tie clasp on my tie. Then Bill Ludwig would walk away. That was a really meaningful gesture. This tie clasp is the one that Bill Ludwig gave me to put on my tie. I found out later that he had a bunch of these tie clasps laying around. So, I learned another little lesson from that experience - don't think you're too special (laughs)! “

Great mentors in my life – Bill Ludwig and my Dad:

“Bill Ludwig was such a masterful tactician of things. But he was also a player and a brilliant business guy. The Ludwig guys like Chuck Heuck who worked on Damen Avenue for about 12 years, said they were scared to death of Bill. He was the owner. When you own something and you're the president, you have to be a different person. After Bill Ludwig retired, he was more like a grandpa, just happy to be working in the drum business. That's one of the reasons why we probably got along so well. As a result of that, he was able to impart a lot of knowledge, a lot of information to me, that other people didn't get. You know, when I was a kid, my dad was involved with credit unions and financial types of things, although his main job was being a letter carrier. He would say, “Jim, here's some information about money and saving, investments and stuff like that.” And I’d say, “Oh, yeah, Dad. Sure, yeah. Okay.” So, I go on through life, and then I get into business. My dad's been gone 30 years now. But I remember him saying, “Jimmy, you're doing so well. I didn't think you were paying attention to me.” And I said, “Well, I guess I was, but sort of subliminally.” And in many ways, that's sort of what happened with Bill Ludwig and many other people; they weren't taking him totally seriously all the time. But I was. And so that's how we connected so well.”

Thoughts on Managing Upward:

“I had 34 bosses in 36 years at Ludwig. Each time you have a boss change, you can have what's called a polar opposite change. A new boss comes in; he says we're going this way. All right, we're going this way. Oh, they're gone and now there’s another new boss. All right, we're going this way. And you ping-pong, back and forth. Part of our job, my job, was to manage that. Because if we kept this back-and-forth thing going, it could destroy our brand. So, we managed to filter that and to keep it going. One of the cool things about Ludwig was that key people cared enough about the brand and fought back by making important adjustments. But certainly not enough to get you fired; you had to balance it.

So that is my story. Now, between myself and some of our other colleagues, we kept Ludwig alive for the next generation. I always felt so honored that I had this opportunity to work with a legacy brand like Ludwig.”

Audience Question -

Question: I was just wondering if Bill Ludwig explained to you his logic and reasoning for selling the company?

JC: “It was very simple. Increased competition from Asia. What was the number one thing that the import drums were able to have as an advantage over a company like Ludwig? Cheap labor. But also hardware! Hardware at this particular time was getting bigger. We were older people that liked the lightweight hardware. I didn't want to carry big stuff around. But in this era of the late 70’s or early 80’s, big hardware was the king. In addition, America became more environmentally conscious. The one thing that was essential for hardware was chrome plating. Chrome plating in the United States kept going up and up in price, and you couldn't even find people that would do it. Why? Because it was environmentally unfriendly. Countries like Taiwan, and then later China, the pollution restrictions were not as tight.

Can you imagine having to walk through the factory, knowing that hardware has to start coming from offshore sources and that in time many people are going to lose their jobs? And you're the person that is leading that charge? When you're 29-30 years old, that weighs very heavy on you. You try to tell yourself that these people don't really like me that much anyways, and you have to start getting stuff from Taiwan. On the other hand, if you didn't, the alternative was Ludwig was going to go out of business. We did whatever we could in order to keep the brand going.

How many people remember the Rocker and the Rocker Two series of drums? Yeah, those were made in America. But they were a blended kind of a thing, where I started getting hardware offshore. We’d make the shells in America, buy the hardware from Taiwan, and assemble it all in America. But you see, as all business goes, prices rise. It came to a point where Ludwig could no longer afford to make the drum shells here. So once again, my responsibility as the Marketing Manager wasn't just marketing, I was also the lead to say in product sourcing. So, I had to go back to Taiwan and say, “I need to get the whole drum set from Taiwan.” And that was also called Rocker. And then later on, we did it with Accent. There was a steady progression as prices rose, and we had to keep finding sources that were more economical in order to stay in business. That was the way to stay in business.”

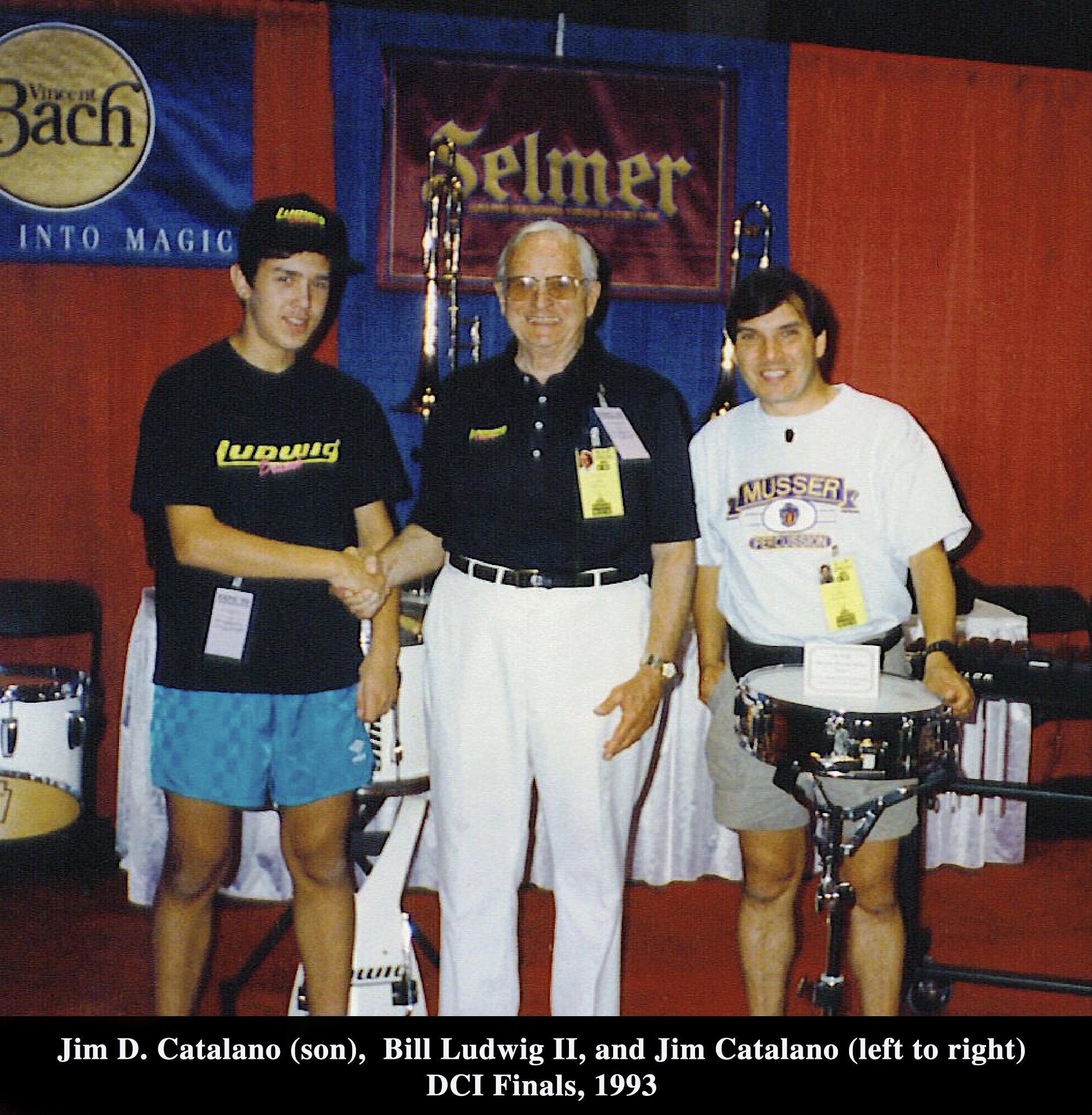

Postscript: Not one to slow down in retirement, Jim has continued to be very active in the local Elkhart, Indiana music scene and teaches part-time as an Adjunct Assistant Teaching Professor for the University of Notre Dame, St. Mary’s College. Jim now attends the Chicago Drum Show as an exhibitor with his own booth of rare, unique Ludwig drums, apparel, and collectibles. Jim’s son, Jim D. Catalano, is now 43 years old and also quite a talented drummer. The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree…