Pete Cater was born with a drumstick in each hand. His father was a drummer, and his grandfather a saxophonist and bandleader. Pete’s precocious rhythmic awareness was apparent from the outset. Movie footage exists of him hand drumming aged barely 12 months and the innate talent cannot be missed. His musical tastes matured similarly early, and courtesy of his Dad’s record collection he was, by age five, already a devotee of Louie Bellson, Joe Morello, and Buddy Rich. The following year it was a television appearance by Rich on the UK children’s magazine program “Magpie” that proved to be the turning point in Pete Cater's evolution. At 19, he became the youngest member of the 'All Stars Big Band', an 18 piece made up of top players in his home city of Birmingham, England. That same year the first incarnation of the 'Pete Cater Big Band' made its debut. In 1992, Pete had occasion to play with Cuban trumpet virtuoso Arturo Sandoval. So impressed was Sandoval that he offered Pete dates in Europe later that year doing concerts paying homage to Clifford Brown. In 2002 Pete was elevated to the ranks of British jazz royalty when he was first choice to replace the late Ronnie Verrell (‘Animal’ from the Muppet Show) in the Best of British Jazz, an all-star sextet under the leadership of trombonist Don Lusher. Pete Cater continues to care passionately that big band music is sustainable and properly represented in the ever more diverse contemporary music scene. Pete’s next album although not a ‘tribute album’ as such, will be honoring the influence of Buddy Rich's fantastic musical legacy.

“A gifted and versatile drummer, at home in any context”

(Rough Guide to Jazz)

"So much of our early experiences of music start with the family record collection. My Dad played drums and was a huge fan of Gene Krupa, Joe Morello and Buddy Rich, and my earliest years found me developing a precocious affinity with these drummers, and to a lesser extent, Ed Thigpen, Max Roach, Sonny Payne, Shelly Manne, Cozy Cole, Philly Joe Jones, and several others. All this came about thanks to the jazz albums that were played at home. I consider this to have given me an amazing head start as a musician, far more advantageous I believe than family wealth or industry connections might have been.

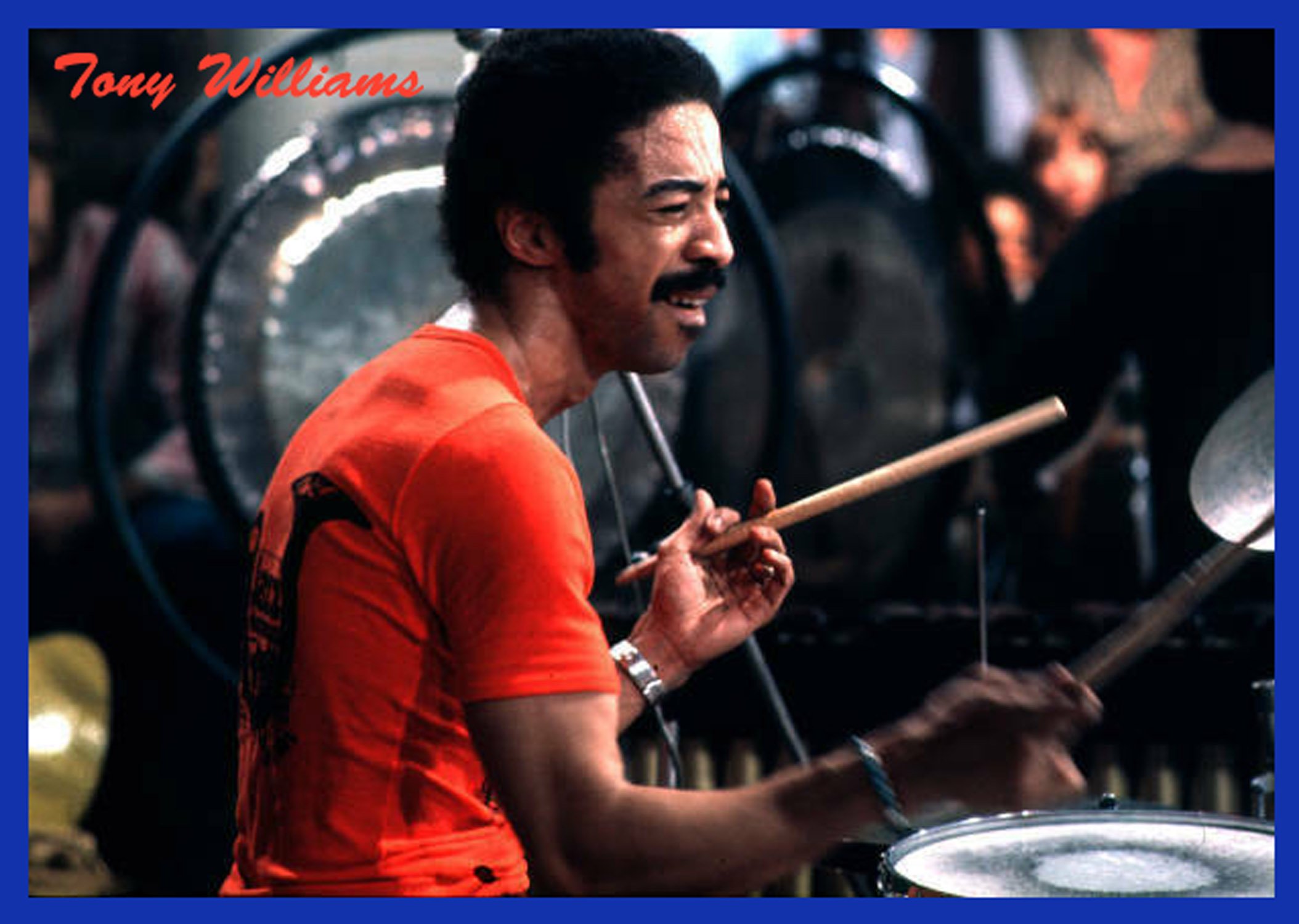

Also, throughout my young years there was an abundance of jazz on local and national radio, and it is highly likely that this was how I first came to hear Elvin Jones, Roy Haynes, Tony Williams, and a great many more significant, influential players, almost certainly without actually realizing it at the time.

My formative playing experiences as a working drummer were with musicians from my Dad’s peer group, and their tastes were similar to his, largely favoring more mainstream jazz over the innovations of the 1960s and 70s. However, as I got a little older and started to get to know more musicians, including those of my own age group, the spectrum of influence grew far wider, and I was steadily compiling a list of names from music magazines, drum catalogues, and books detailing famous players’ cymbal set ups.

Finding out about as many different jazz drummers as I could became a borderline fixation, and although a lot of my early playing reflected strong influences like Buddy Rich, Louie Bellson and Butch Miles. I was starting to hear other sounds, even though my hands and feet were nowhere near being able to create such sounds, and even if they had, my home city was not knee-deep in performance opportunities at the more progressive end of the jazz spectrum, especially not for 15 year olds who were rather too taken up with their solo chops.

The change came in 1979. Having discovered Charlie Parker courtesy of a television documentary a couple of years previously I had started to develop some knowledge of bebop and what would follow in its wake, as well as the great innovators of modern jazz drumming, particularly Art Blakey and Roy Haynes, both of whom had featured prominently on BBC’s television coverage of the Montreux Jazz Festival.

Like with Buddy Rich a few years previously, the visual impact of actually seeing these players do their thing was far more powerful than just hearing their recordings. Still no sign of Tony Williams though, but don’t forget how relatively slowly information used to travel in the pre-internet age. The pace of information did start to quicken when American jazz and drum related magazines started to become more readily available. One early acquisition carried an advertisement for Tony’s then current record release, entitled ‘The Joy of Flying’. This was the first time I knew for sure that I was listening to Tony. I perfectly liked the record but frankly it wasn’t a game changer for me. I had already dug into some of the standout jazz/rock ‘crossover’ drummers of the era, most notably Mike Clark and Lenny White, and I sort of mentally ‘filed’ Tony alongside these guys based on what I had heard on his latest album. Big mistake. Another big mistake was my dismissal of a transcription of Tony’s legendary ‘Seven Steps to Heaven’ solo in a drum magazine. I didn’t pay it much attention at the time because it ‘didn’t have very many notes in it’, such was my obsession with speed and facility. Teenagers, eh?

Salvation was at hand, this time courtesy of ITV, the UK’s commercial television network, when once again the moving image played a pivotal role in my enlightenment. The following year a documentary aired featuring a clip of Tony Williams setting fire to a satin flame finish Gretsch set with Miles Davis in Stockholm, 1967. The clip must have lasted all of 30 seconds, but that was all it took for me to have a new drum hero. Having been slightly disappointed with his then contemporary style (Million Dollar Legs) - a case in point for me the ‘old testament’ Tony embodied hipness on the drums quite unlike anyone I had ever heard. This is a point of view I pretty much stand by over forty years later.

So there then began a quest to source as much of his earlier work as I could. Back in the 80s that was easier said than done, as this was a time before CD reissues and everything being available online for free. Records got released, were available for a while, and were then deleted. A consequence of this was that amongst my peer group of young musicians we mostly listened to what was then currently available, Weather Report, Chick Corea. Miles’s more recent output and so on. Earlier jazz was what got many of us started, but was the preserve of our parent’s generation. No emerging young musicians (with the notable exception of saxophonist Scott Hamilton) were setting about forging careers in jazz by revisiting the sounds of a previous era in a way that is now commonplace in our postmodern age.

As luck would have it, there was a specialist jazz record store in Birmingham, (UK, my home city). They had a good selection of reasonably priced second hand vinyl unlike some of the London stores who would charge sky high money for out of print titles. The first Miles/Tony release I picked up was ‘Miles Smiles’, followed by ‘ESP’, ‘Four and More’, (still my go-to reference when students ask what up-tempo ride ought to sound like) ‘My Funny Valentine’, ‘Miles in Europe’ and perhaps the greatest of them all, ‘Nefertiti’, with its iconic title track consisting of a single idea wherein Tony’s drums weave in and out of the ensemble, drawing on a seemingly endless well of creativity, constantly responding, punctuating, avoiding ‘licks’, and clearly playing in the moment. His extraordinary body of work as leader of his own groups I would discover later, but it was the daring, ground breaking, game-changing innovations of the young Tony, coupled with the iconic drum and cymbal sounds, that would have the farthest reaching impact on my whole conception of what the drum set is all about.

Tony was, in my opinion, one of the few master improvisers of our instrument. He added significantly to the vocabulary of jazz drumming and though his earliest recorded output is now over sixty years old, it nonetheless sounds as ground breaking and innovative as if recorded yesterday."

-- Pete Cater