From The Army to New York’s Village…and Beyond

Here’s a story that proves you don’t have to be a superstar to have a remarkable drumming history.

In 1955, Harvey Wolfson was a twenty-two-year-old drummer. He was also a soldier—serving in the 74th US Army Band at Fort Campbell, Kentucky.

“I had a jazz band within the Army band,” Harvey recalls. “We would play for the general or at parties. At a jam session we had one time, a guy from Nashville came in. He had a full hillbilly image, including a piece of straw in his mouth. His name was Willie Hogshead, and he told us that he was from the Grand Ole Opry. He asked our bandmaster if we had a drummer who could read sheet music. He said, ‘We have special arrangements for some of our stars. We need a drummer who can read the music and cut records with those stars.’

“The bandmaster called me over and said, ‘Do you wanna go to Nashville?’ And I answered, ‘Why not?’ So I went to the Grand Ole Opry, and I recorded with Glenn Campbell and several other stars.

“In 1955 our band entered the All-Army Entertainment Contest for instrumental groups,” Harvey continues. “We won at Fort Campbell, in the preliminaries. Then we competed at Fort McPherson, Georgia, against all the Third Army forts in the Southeast—and we won that. Throughout all this I had been using my own drums, not the Army’s drums. They were a used Gretsch set that I’d bought a few years earlier.

“Next, we went to the US-wide competition, and we won that…again with my own drums. Then we went to the final competition for all the service bands stationed all over the world. And we won that.”

The contest Harvey describes had two divisions: instrumental ensemble and solo instrumentalist. Harvey’s band took the former title. The winning soloist was a drummer named Rufus Jones—better known to drummers as Rufus “Speedy” Jones. He’d been drafted while playing with Duke Ellington. More about him later.

“After our band won the worldwide contest,” Harvey says, “we appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show. Then we became part of the Army Special Services, which meant a transfer for me to Fort McPherson, where that outfit was based. We created a show that toured the United States, doing a lot of local TV appearances and charity performances.

“By now it was 1956, and my drums were getting pretty worn and shabby from all the traveling. So I talked to the officer in charge of the tour, whose name was Lieutenant Whiting. I told him that I’d pretty much used my drums up playing so many dates. He told me to go to the music store in downtown Atlanta and order whatever I thought I was going to need, and send the bill to him.

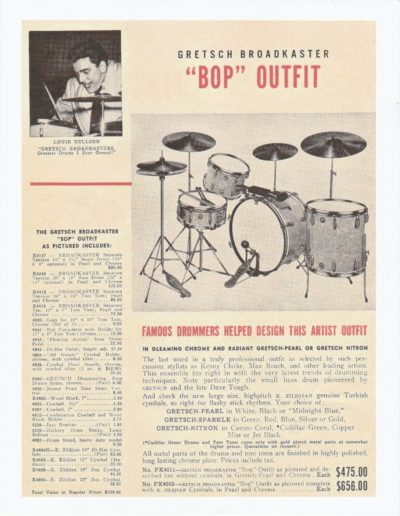

“I went to the store and ordered the best set of drums that I could find in the Gretsch catalog: a Broadkaster ‘Bop’ outfit, including two 22″ K Zildjian cymbals. One was a ride; the other I taped a quarter to in order to create a ‘sizzle’ cymbal. Now I had a great set of drums that could take the wear and tear of travel…the load-ins and pack-outs, and airplane trips, and so on.”

Over the eighteen months that Harvey toured with the Special Services show, he and Rufus Jones became good friends. In that show, Rufus had his own solo act on the drums. “Rufus had Slingerland drums in the same white marine pearl finish as my Gretsch drums,” Harvey recalls. “When he did his act, he borrowed my 16×16 Gretsch floor tom so that he’d have two floor toms. At the end of the show he’d give mine back to me. On the last show that we played together, before I left the Army in August of 1957, Rufus returned the floor tom as usual. But he accidentally gave me his Slingerland drum instead of my Gretsch drum! I didn’t notice it, because they were virtually identical, and we were packing up and leaving in a hurry.”

When the Army tour finished in 1957, Harvey received a pretty enticing job offer. “Lou Walters, who owned the Copacabana nightclub in New York, had been one of the judges at the Army contest. He asked me if I’d like to play for his show in New York—and he offered me a lot of money for those days. But I had a degree in marketing and economics, and I wanted to use that toward a career. I thought long and hard about it and decided that I wanted to marry and settle down and have a family, instead of playing and traveling.”

Over the next few years Harvey did just that. He and his wife moved to Wilmington, Delaware, where they had two children. But drumming still beckoned. “Frankly,” says Harvey, “I wasn’t earning a lot of money at my day job. So in 1959 I went to a jazz club in Wilmington, and asked if I could sit in. Before the night was over they asked me to become the house drummer, and also to play the New York shows that came through Wilmington. And I said ‘yes’. It wasn’t hard work—it didn’t involve traveling—and of course my Gretsch drums were just perfect for the job.”

Harvey re-connected with his friend Rufus “Speedy” Jones later in 1959. As Harvey tells it, “Rufus was playing with Lionel Hampton in Atlantic City, and he invited me to come down and catch a session there. I did, and I brought his Slingerland floor tom with me. I didn’t know whether he still had my Gretsch tom or not. But I put his drum in the car, just in case.”

Rufus and Harvey chatted during the break between halves of the show, after which Harvey returned to his seat in the audience. “In the second half of the show,” says Harvey, “Lionel Hampton suddenly said, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, we have a star in our audience, who I’d like to bring up to play with us.’ I’m looking around to see who this star is, and he calls my name—much to my surprise. So I went up and sat behind Rufus’s set. And one of the first things I did was look at his two floor toms. But neither one was mine.”

In 1960 Harvey took a full-time job with a business in New York. “Naturally I took my drums with me,” he says. “I started playing at a Greek Hall in Greenwich Village, with a group called ‘The World’s Oldest Floating Dixieland Jazz Band East Of The Mississippi.’ It was made up of guys like me, who had once been full-time professional musicians, but were now in business. It was a very interesting thing for me to do twice a month on Thursday nights.”

One of the members of that band also played at the Village Vanguard on Monday nights—which was a happening gig at the time. “He came to me one Thursday and said that their drummer was ill, and they needed a sub. Could I cover for him on the next Monday night show? I did that, and it was the last professional job I played—that I got paid for, anyway. There were some great musicians in that band, and it was a joy to play with them.”

In 1964 Harvey and his family moved to Philadelphia, although he continued to work in New York. He couldn’t go to those Thursday night sessions in the Village anymore, because of the distance. “I was gaining ground in business,” says Harvey, “and that was taking most of my time. So my drums got packed up and put away.”

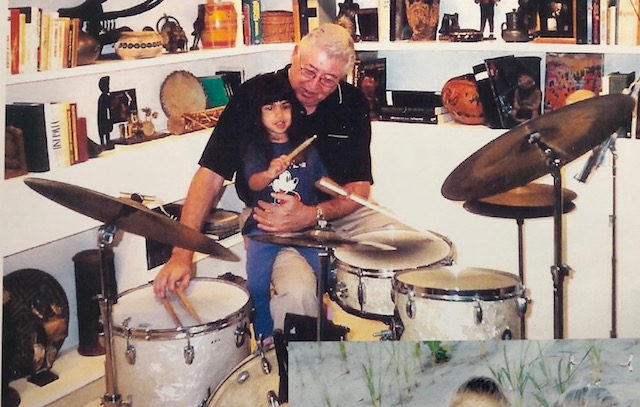

In 1998 Harvey’s grandson, Jack, was born. “I had a music room in our house,” Harvey says, “and I put my drums, a piano, and a stereo in there so I could practice with anyone I wanted. When little Jack was about six months old, I’d sit him on my lap behind the drums. I’d play a simple beat pattern on the snare drum with my finger. I’d play it twice, and then I’d say, ‘Jack, you play it.’ He understood, and he played it. Of course, all little kids like to beat on a drum. But I found out that he had a musical memory.

“Over the next several years I taught Jack, a little at a time. Rudiments…how to read music…and so on. Eventually Jack’s family moved to Bala Cynwyd, a suburb just north of Philadelphia. He could no longer come to my place on a regular basis, so I loaned him my drums. He put them in his basement so he could play them and practice as much as he wanted. I knew he’d take care of them. His father put new heads on them for him…except for the front bass drum head, which had my initials still on it like Gene Krupa used to have.”

Fast-forward to 2018. Jack is a now a sophomore at Drexel University. He doesn’t have time to play the drums. His father calls Harvey and asks what should be done with the drums. At this point Harvey is eighty-five years old, and health reasons make it impossible for him to play the drums himself.

“I had to hang up my sticks two years ago,” Harvey says. “Today I live in a very comfortable retirement home. But I can’t very well set my drums up in a one-room apartment in a twelve-story building just for sentimental reasons. So they’re in my grandson’s attic in Bala Cynwyd, near Philadelphia. It was a top-of-the-line 1956 Broadkaster kit, ordered specifically for me by that Atlanta music store, directly from Gretsch. The set has a 5 ½x14 snare, a 14×22 bass drum, and a 9×13 tom-tom that mounts on the bass drum—all covered in white marine pearl. There’s also Rufus Jones’s Slingerland floor tom. The set also has most of the original Zildjian cymbals, including the two 22″ cymbals and a 14″ crash. [The hi-hat cymbals are with an electronic kit Harvey purchased a few years ago.] I upgraded to some heavy-duty contemporary stands several years ago, so they’re part of the kit, as well.”

As we suggested at the opening of this story, Harvey Wolfson may not be a superstar. But he and his Gretsch kit share a fascinating history, based on the unique experiences of a talented professional drummer.

-republished from the Gretsch web site with permission