Not So Modern Drummer continues to celebrate the legendary Buddy Rich in 2017. Recognizing the 100th anniversary of his birth… Contributing their personal recollections and commentary on Buddy Rich are: Dan Britt, Bob Campbell, Skip Hadden, Bruce Klauber, and Andy Weis.

Dan Britt

When I was a kid, before I ever played drums, my uncle said, "Dan, check this out - this is the best drummer in the world". And I watched the amazing Buddy Rich playing on TV. A few years later, luckily, Buddy played in Cresskill, NJ, the next town from me, and I saw him live! I became a drummer after that. It's fascinating to watch Buddy play,and to watch his hand technique. He's a true inspiration, and every drummer I know is a huge fan!

https://www.facebook.com/DrumTeacherDanny

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XSUkXFV0MPg

Bob Campbell

"Buddy Rich has been one of my drum heroes from the very beginning when I was first learning to play the drum set. He was one of the few drummers, like Krupa and Bellson, who was featured in their bands and had enormous technical skill. In 1975, I was 15 years old and had been attending a Jazz Workshop at Ramapo College in New Jersey. It was two weeks total emersion into jazz by some of the finest players in the music business. On one of the evenings in July, the Buddy Rich Orchestra came to the college as part of the workshop concert series. I vividly remember Buddy going on stage first without his band and immediately launching into an amazing solo. The dexterity of his left hand (one of my weaknesses) and blazing speed were absolutely amazing. Buddy knew that many in the audience were students or faculty attending the jazz workshop. So, he offered a short lesson to these students. He stated that dynamics were really important and that this was accomplished not by microphones or amps but by the drummer. He had the soundman turn off the mikes. Buddy started playing quarter notes softly on the bass drum, then stopped. After a short pause, Buddy slammed his bass drum beater into the head, producing one of the loudest, most percussive sounds I have ever heard come from an unamplified drum kit. He then hit it again, even louder! You had to be there to believe the volume he achieved with his foot. Then he discussed some of the rudiments, focusing on the roll, He started off very, very softly and slowly proceeded to get louder. He switched from double-stroke to single, and played faster…and faster…and faster. The other drum students and I were just blown away. The audience responded with thunderous applause when he finished.

I still remain fixated on his left hand. Gosh, I wish I had half that much control and speed! He played with his band the rest of the night, and as expected, we were all captivated by the great sound and technical expertise. These were phenomenal players. At the end of the evening a bunch of students and I went to get Buddy’s autograph. Unfortunately, Buddy wasn’t signing or meeting people after the show so I never got the chance to talk with him in person.

The next day, some of Buddy’s band came to the workshop and we got to chat a little. They remarked how Buddy was very demanding and a perfectionist, but that they really enjoyed playing with him and so many other talented musicians. Jokingly, one of the sax players said that Buddy would rush the tempo now and then, but would never admit it. It was always the band’s job to follow the tempo! Clearly, Buddy worked the band hard but the result was one of the best jazz orchestra’s in the country, if not the world.

So over 40 years later, I remember Buddy with great admiration and respect. I try to emulate him by aspiring to play better technically, in the groove/pocket, and with dynamics. However, my left hand is sadly still not half as good as Buddy’s!

http://www.nytimes.com/1975/07/13/archives/jazz-workshop-at-ramapo.html

https://www.facebook.com/bob.campbell.33

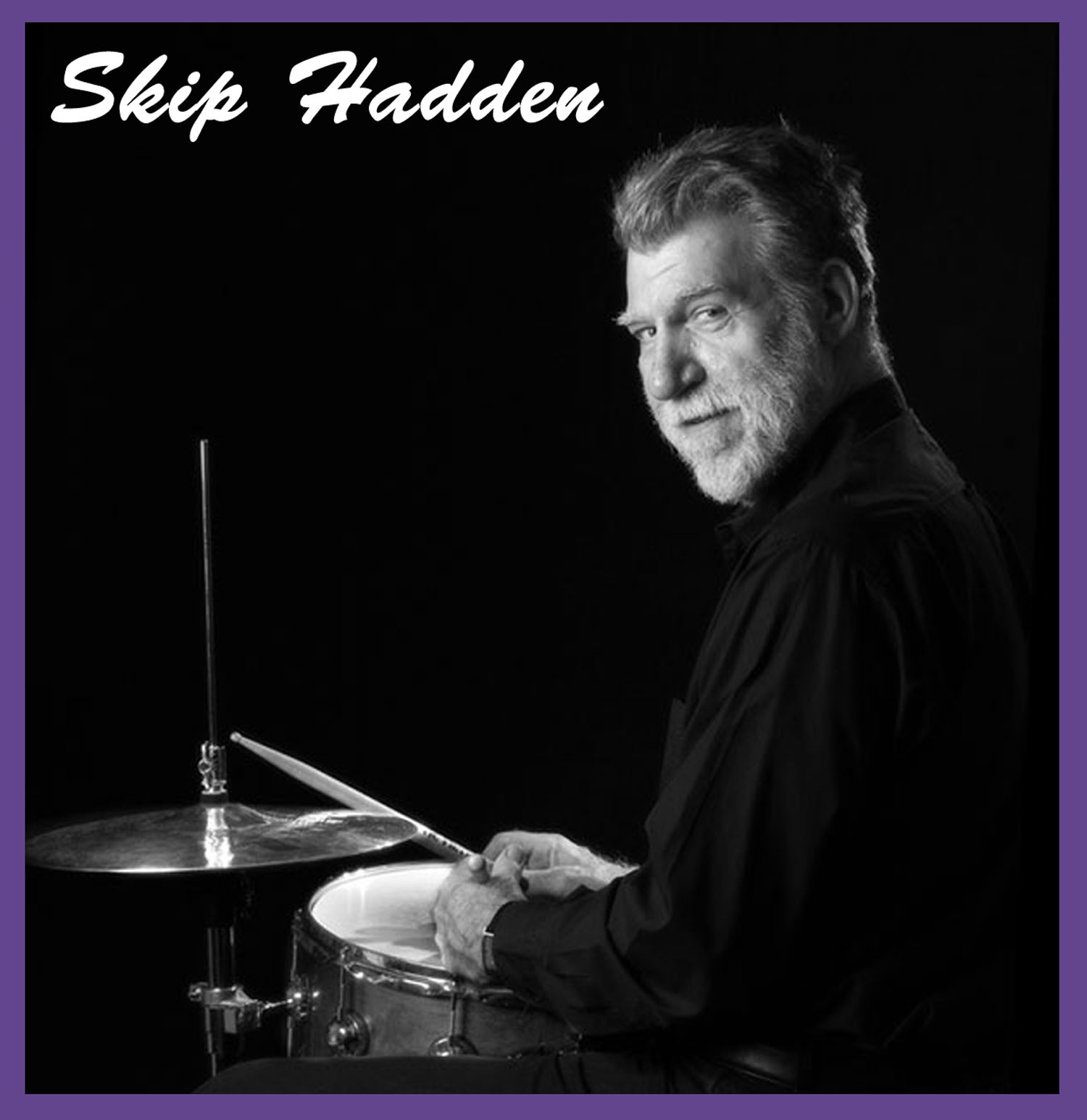

Skip Hadden

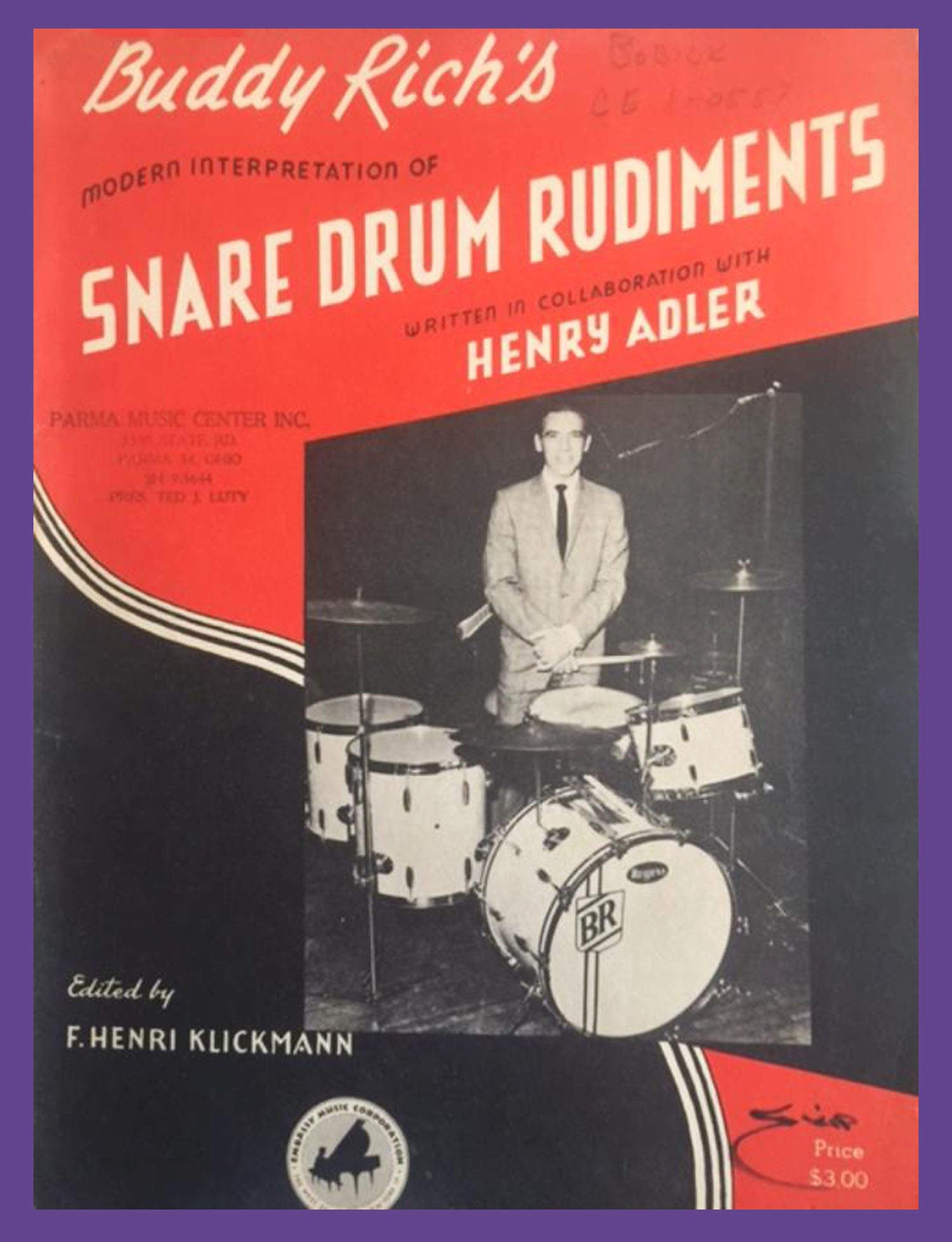

I have thought long about what an influence Buddy Rich had on my drumming. There have been so many great and insightful reflections by some many great players I have been a bit daunted about my input into this 100th anniversary celebration of Buddy Rich’s life and his impact. The influence was all totally indirect. I studied with his book “Modern Interpretation of Snare Drum Rudiments: written in collaboration with Henry Adler”.

My teacher was Eddie Bobick, who had been Buddy’s drum tech or as he stated his “band boy”. I still have the book and all of Eddie’s adjunct comments, interpretations and lessons dealing with their use in different musical styles in another spiral bound book. It was through Eddie Bobick and this material that I became aware of just what it took to accomplish any kind of expertise on the instrument.

I had seen Buddy Rich on television, my only exposure to him, and this brought it full circle. Through this more personal connection, through Eddie Bobick, to the art of drumming I understood.

In retrospect I guess this is an illustration of just how influential, how deeply, how broadly, how profoundly… one person's impact can be… to jump generations, decades and now centuries. The beat goes on…

https://www.facebook.com/skip.hadden.3

Bruce Klauber

In 1960 I was eight years old and had just started taking drum lessons. My father took me to hear Buddy Rich, then appearing for one night only at the St. Joseph’s University Field House in suburban Philadelphia with the Harry James big band. After that concert, my life was changed. In the 27 years that followed, if Buddy Rich was appearing within 100 miles of my Philadelphia home, I was there, even if I didn’t have enough bread to get into the club or concert hall. For the record, on those many occasions when money was short, the evening was spent with my ear to the wall – closest to the band, of course – of the club or concert hall. No heed was paid to the fact that the weather outside was often below freezing.

Like thousands of other young drummers at the time, whether they want to admit it or not, I wanted to play like Buddy, have the brand of drums Buddy was using, wanted to use the drum set-up Buddy used, and wanted to look and act like Buddy Rich. That’s what young folks with idols do, I guess, and truth be told, if someone told me that Buddy ate peanuts for breakfast, my diet would have been changed the next day.

After a while, at least some of us ultimately realized we couldn’t do what Buddy could do on the drums. Quite simply, on a technical basis, what he played was not possible to be played, and it will never, ever—in my view—be equaled or surpassed. But the lasting contributions of Buddy Rich went way beyond what he could do in a drum solo.

To these ears, he was the complete accompanist who had an electrifying fire that could inspire a soloist to play way, way beyond himself, or herself. That, by the way, has nothing to do with volume. It has to do with emotion, intensity, and yes, sensitivity. Sure, this was a man who drove a fiery, high-energy big band. But this was the same artist who backed—with absolute love and respect—legends like Louis Armstrong, Art Tatum, Benny Carter, Lester Young, Nat Cole, Charlie Parker and dozens of others in small group settings. And what player on any instrument do we know of who evolved from a swing player with Tommy Dorsey and Artie Shaw to a drummer who was often described as “the greatest drummer who ever lived"?

In my later years, when my career was eventually split between being a working jazz drummer and that of an author, columnist and journalist, I got to know Buddy Rich and spend time with him. And I’ll say that he was as unique as a human being as he was as a player. He cared about jazz and those who played it—he loved Gene, he loved Papa Jo Jones, he loved Louie Bellson, he loved Philly Joe Jones -- and all he asked of the youngsters who populated his band in later years was for the 110 percent that he gave of himself nightly. He abhorred those who imitated him or imitated anyone else. “If I want to hear Cary Grant, I’ll listen to Cary Grant, not Rich Little impersonating Cary Grant,” he told me. And while he was secure with whatever place he might have had in history, he staunchly refused to discuss the past, saying that “to be a part of history is bullshit.” His interests, he added, were only “today and tomorrow.”

During the production of the “Buddy Rich Jazz Legend” DVDs and various others that involved Buddy—produced in conjunction with daughter Cathy and the Rich Estate-- and even during interviews I’m asked to give now, a certain subject always comes up when speaking about Buddy Rich, the man. Here’s the answer recently given to WXPN Radio:

“Buddy’s temper was no secret. The infamous ‘bus tapes’ have become the stuff of legend. But there are a couple of things to take into account about this man. He was performing on the vaudeville stage from the age of 18 months old and came up in an era where you scratched and clawed your way to the top. And this was also a man who played with every giant of jazz in the universe; giants who personified perfection and professionalism and never gave less than 110 percent of themselves. So what did a guy like Buddy Rich do when he found himself surrounded by a bunch of kids in the band who, from time to time, showed themselves to be a bunch of self-indulgent, amateur slackers who he knew were capable of giving and being much, much more? The Buddy Rich I knew and loved was a man who cared deeply about jazz and those who played it, about respect, about professionalism, and about never asking that anyone give any more than he did: 110 percent perfection.”

Most of us who worshiped Buddy Rich and ate what he supposedly ate for breakfast grew out of that hero worship, which eventually morphed into just genuine, mature respect. But, you know what? Almost 60 years after I first heard him play, there’s still a part of me who really wants to know what this legend ate for breakfast.

Bruce Klauber is the biographer of Gene Krupa, producer of the “Buddy Rich Jazz Legend” DVD, Warner Brothers/Hudson Music “Jazz Legends” DVD Series Producer, a syndicated columnist, singer, multi-instrumentalist and recording artist. As a jazz drummer, he has worked with Charlie Ventura, Al Grey, Milt Buckner, Joanie Sommers, and Pepper Adams, among many others. His new book, “Reminiscing in Tempo,” which recalls his personal association with everyone from Lou Rawls and Mel Torme’ to Frank Sinatra and Buddy, will be published next year by Hal Leonard/Centerstream.

http://thejazzsanctuary.com/bruce-klauber/

https://www.facebook.com/bruce.klauber

Andy Weis

The 1st time I saw Buddy Rich was at a concert that my parents took me to on July 2, 1967. I was 13 years old and it was at the Civic Arena in Pittsburgh, Pa. On the bill was Pat Henry (comedian), Sergio Mendes and Brasil ‘66, Buddy Rich and his Big Band and Frank Sinatra. After Pat and Sergio did their sets, Buddy and the band did a great set featuring many of the tunes from Big Swing Face and Swinging New Big Band. Then there was an intermission and then Sinatra did a set with Buddy’s band that lasted well over 90 min. It was pretty much the same show as “Sinatra at the Sands” which was recorded in Sept of that year. I was sitting pretty far back but I could have sworn Buddy played Sinatra’s set.

The second time I saw Buddy and the Band was in 1970 at Paul’s Steakhouse in Olean, NY. I was from Saint Mary’s, PA and a friend and his family asked me if I would join them because they were driving up to see the concert which was about 60 miles away. I remember I was 15 at the time, so the concert would have been before July. I was really excited because I had just bought the Mercy, Mercy, Mercy LP. The band came in first and somehow I found myself in the dressing room. I introduced myself to Pat LaBarbera and he was just getting his tenor sax out. Even though Don Menza did it on the LP, I asked Pat if he would play a “super-Rollins” cadenza as it was described on the album. He DID! I was stoked, but not as stoked as I would be at what was to come. Buddy and the band played an incredible first set (of course) and it was time for an intermission. It was to last almost an hour. Early in the intermission I saw Buddy sitting in the corner by himself having dinner. I thought “why not” and excused myself and went over (alone) to Buddy and asked him if I could join him. He said, “Yes”. And that started an almost hour long one on one conversation. He was the NICEST guy you could ever meet and he let me ask any questions I wanted. Well, almost. Not long before he had switched from Rogers to Slingerland Drums. I had noticed that he had a Rogers snare, 2 Rogers cymbal L-arms and a Rogers Swivomatic bass drum pedal. I asked him about these items and he gave me a funny look that told me to change the subject FAST! Well, after he ate, I asked him if I could have my picture taken with him and he said “yes”. I had one of those crappy Polaroid Swinger instant cameras and all of the pictures I took that night had a line in the center when they developed. Now we get to the second set and it was even more incredible than the first and he came down to talk to the audience. He asked what we would like to hear and everyone started yelling out requests. I was yelling “CHANNEL ONE SUITE” and he stopped and looked at me (I was sitting in the front) and said “Hey kid. How old are you”? I replied, “”I’m 15”. He then said, “Do you want to live to be 16”? Everyone laughed including me. He then went back to his drums and played Channel One Suite. I will never forget that night.

When I went to study with Alan Dawson in 1973 in Boston, I saw Buddy in concert a third time at Paul’s Mall. I moved to California in 1980 and saw Buddy and the band at a shopping mall south of San Francisco in (maybe) 1984. The last time I saw Buddy and the band in concert it was, I believe, in 1985 at a place called The Club in downtown Monterey, Ca. Before the concert, a friend and I were sitting in a small café. Buddy came in with his manager and piano player and sat right next to our table. I just happened to have my “We Don’t Play Requests” book with me, and he graciously autographed it!

I agree with all of the positive superlatives that people use in describing Buddy Rich. On the other hand, I think it’s sad that many people (in my opinion) define who Buddy was as a person by the infamous “tapes”. Fact is, had he wanted, he could have played only with the greats. But he was generous. He gave many younger musicians their big break and the chance of a lifetime by hiring them to play in his band. They could have left at any time if they didn’t like him. They didn’t. Buddy was a perfectionist. He gave his all in every performance and he expected a certain standard from his musicians that he knew they could maintain. When they didn’t play as well as he knew they could he got mad. So would I. For me, Buddy still lives because there are still “new” things on coming out YouTube that have never before been seen and heard by the public. Just when I think I’ve seen and heard everything, someone posts something totally different that Buddy did. I still remember April 2, 1987. It’s hard to believe it’s already 30 years ago. And despite the fact that all of those years have passed, he’s still known as the greatest drummer that ever lived.