For those of us who listened to music and learned to play drums in the sixties or seventies, our drumming heroes played organically, and without clicks. They typically had good time, and during the sixties in particular, their drums sounded open and natural without excessive studio processing. You know, real. Well, that's the era I grew up in and began my development as a drummer, and I always had a soft spot for the old songs, the classic drum sounds, and a simpler approach to drumming.

On September 14, 1980, I met someone that would motivate me to open my ears, and my mind, regarding the drumming protocols I'd held onto for many years. It was a little known accordion-playing parody/satire artist named "Weird Al" Yankovic, at the broadcast studios of the Dr. Demento radio show in Los Angeles. Al debuted his new Queen parody - "Another One Rides The Bus" - live on the air, and asked me to pound out the beat on his accordion case. Afterward, I suggested he have a band, and I'd be his drummer. It was the start of a lengthy and rewarding musical journey for me.

Let's jump ahead to our first album release in April, 1983. It was recorded at the legendary Cherokee Studios and produced by Rick Derringer, and the approach was basically a rock band, fronted by Al's rock & roll accordion stylings. Half of the songs were humorous parodies of recent hit songs (for which he would become best known) and half were Al's originals with a comedic, satirical twist. There was no attempt then to replicate the sound of the originals we parodied. The gimmick was the accordion, and that worked well enough at the time. MTV was in its infancy, and the "Ricky" and "I Love Rocky Road" videos were in rotation. We had made a nice splash.

The second album, "In 3-D" (February, 1984) was a turning point for a few reasons. Unlike the first album, we recorded everything to a click, added some effects to my drums, and used a machine on one track. It also heralded the beginning of the notion that if we made the parodies sound like the original song, it would be even funnier. Don't laugh. Rather, do laugh! Copying existing parts and sounds was suddenly added to the band's job description, and the formula worked. It was even applied to the original songs, often done in the style of some of Al's favorite artists. Oh yeah, we also had a worldwide hit witha parody of Michael Jackson's "Beat It" called "Eat It." We were off and running!

Soon after, I bought a Simmons SDS8 "budget" kit, and my first machine, a Yamaha RX11. I realized that I'd need to embrace technology to make sure I could remain the drummer on our recordings. I programmed four of the songs on the 1985 album "Dare To Be Stupid," and also brought the Simmons into the studio for some tom accents. The parodies were getting closer to their original songs' sound, and my listening and programming skills were being cultivated in the process. Looking back, it was pretty elementary, but it was new and challenging at the time.

Many more albums followed, and with regard to drum sounds, mainstream music production was pushing boundaries throughout the eighties and especially in the nineties and beyond. In order to stay relevant with Al, the band had to follow and mimic those trends. My budget initially kept me a little behind the curve technology-wise, but I managed to tread water. I moved up to the Alesis HR16 machine, then graduated to an AKAI S900 sampler, followed by a Kurzweil K2000 sampler module and then the K2600. I confess that I never fully learned how to use either sampler, but in my defense, they weren't designed for drummers. They were keyboardist and producer tools, but that didn't stop me from figuring out just enough to keep moving forward. I used machines, samplers and midi in the studio until 2008, when I began creating studio-ready sequenced drum tracks at home... the kind you can simply upload to the studio's dropbox.

When listening to music, I naturally pick out the drums, so transcribing parts from hit songs posed little problem for me. It was the drum sounds that proved more challenging with each successive album. Drums in pop and rap genres had become tweaked, filtered, and bathed in digital effects that often made it hard to determine the what original sound might have been. Often, drum sounds weren't even drums! It was a far cry from the fairly identifiable drum machine samples of the eighties. By the late nineties I was creating custom samples on my computer, which gave me enough tools to agonize for days over a track's sounds. Often, it was almost impossible to figure out what the original sounds were, and was frustrating knowing that I'd sometimes settle for sounds that weren't quite where they should have been.

Then, I had an epiphany. Rather than trying to figure how the original producers got their sounds, I only needed to figure out what I had to do to create those sounds from scratch. This shift in perspective made the approach to pre-production easier, and I was forced to develop a better ear and more creative skills as a result. It was a welcomed and necessary step for me both as Al's drummer, and as a musician. I learned to hear the elements that make up a particular sound, and accepted that a snare sound might actually be two or more layered sounds. It was permissible - and I was encouraged - to blend a snare, rim and handclap for example, to get the exact 'clop' needed for the track at hand. It no longer mattered what the original sound was, as long as I could create it from scratch. I also began to respect the portion of a sound that was the engineer's responsibility - I never tried to add reverb or other outboard effects. I'm particularly proud of the sounds I cooked-up on tracks such as "Ebay," "Trapped In The Drive-Thru," "Perform This Way," "Whatever You Like," "Couch Potato" and "Word Crimes."

You may wonder why it's so important to get parts and sounds just right on parody songs, which are essentially just covers with new, funny lyrics. Well, if you've ever seen an interview or read anything about Yankovic, you'd know that he's very meticulous about everything he does. I don't think the word anal comes close enough (which is a strange line now that I look at it.) He writes, produces, arranges, directs, and performs with the fastidiousness of Zappa, McCartney, and Becker & Fagen rolled into one. I know, you don't expect that from Weird Al. But everyone who's worked with him can attest to it, and they 'up' their game accordingly. I should also point out that Al isn't a taskmaster or demanding or hard to work with in any way. His judgment is excellent, and he simply wants what he wants. For those who get it, projects are a pleasure.

However, the backwards engineering and attention to detail didn't apply just to the parodies. Al's originals increasingly became homages to his favorite or popular artists, fittingly regarded as style parodies. On those songs, the band has to approach the playing and sounds as if the subject band had come in to record the track. Unlike most of the parodies, the originals were rarely programmed. We were dealing with live parts and acoustic sounds, and my creativity was put to a further test. I suddenly had to be any number of other drummers, each with their own style and sound. It wasn't as simple as copying their parts and applying them to Al's songs, I had to imagine what that drummer would do if called in to work with Al. On "Craigslist" for example, a Doors style parody, I had to get inside John Densmore's head, and sound like him being the Doors' drummer in a Doors-influenced band. I mention this song in particular, because Ray Manzarek played the keyboards on it (also trying to sound like himself in a Doors-influenced band,) and I knew he'd hear me imitating Densmore! I never got a reaction from him, or Densmore.

Acoustic sounds were a little less demanding than with the samples, but still tricky to achieve. I learned early on that having one kit and a few snares and cymbals wouldn't be a suitable arsenal to meet Al's sonic agenda, and I feverishly began collecting drums and cymbals. I also became increasingly aware about how shell sizes, edges, hoops, head types, tunings and damping affected sounds, and always tried to bring the correct gear into the studio. I paid close attention to how my drums were mic'd and the effect that had on their sound. I was learning by doing - mostly by watching - and it helped make me a more valuable player.

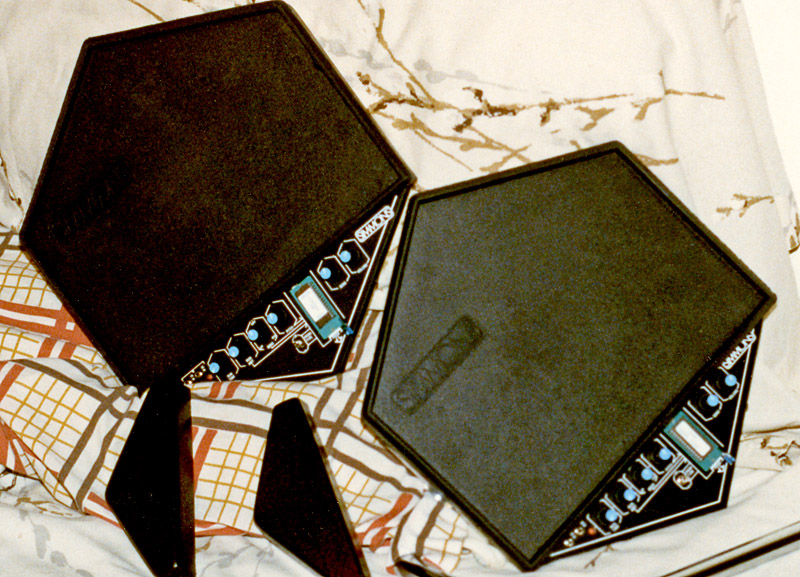

Replicating parts and sounds in the studio was one thing, but pulling it off in concert was another. In the early days on tour, we were basically a 4-piece band: guitar, bass, drums, with Al on accordion and keyboard. We didn't have the budget for the kind of electronics that would allow us to sound closer to our records, but it didn't take long before some technology became mandatory. The 1985 summer tour saw my first use of a drum machine on stage, and our studio keyboardist joined us on the road with his Ensoniq Mirage and the ability to play samples. It was a big step forward, adding sonic legitimacy to the performances. That forward trend continued, and the next tour in 1987 saw more videos and costumes become prevalent in the budding show. The keyboardist now had an Emulator, and in addition to my drum machine, I had a two Simmons SDS-1 pads which played a sample from a single e-prom inserted on to the front of the pad. But e-proms were fragile, so I had a Prom-X custom sample switching box for multiple sounds without changing the chips.

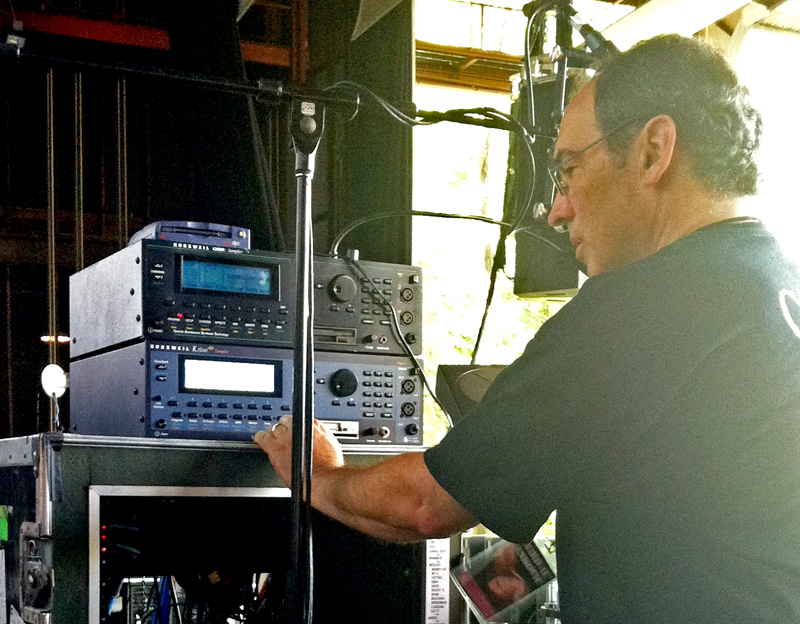

By 1992, we had a tightly choreographed production with more costumes, more videos, hired dancers, and backing track elements played from my S900. I was triggering hits and effects from a first generation Octapad. Within a few years, the technology onstage was becoming more contemporary. Al's new keyboardist had a Kurzweil K2000 keyboard. I had my K2000 rack sampler at my side, triggered by a KAT and able to send stereo tracks to the house, along with a click to me. Using headphones when needed, I could seamlessly sync the band with percussion sequences, backing vocal passages, horn lines, extra guitar parts, etc.

My involvement with technology on stage had gone from zero to state-of-the-art in about 10 years, but the immersion wasn't complete yet. Also, since most of the parodies were sequenced on the albums, I had to adapt and exercise some creativity when playing those songs live in concert. The importance of the video to the show cannot be overstated. It's hard to imagine, but we'd been using a 16mm film projector from 1983 through 1995! In 1996, we made the leap to U-Matic (3/4" tape.) Next came Betacam, then DVD, whose 5 channels of audio that made it easier to employ tracks and clicks during more of the show. The multi-media aspect of the show was now as integral as the band playing and singing, and in 2003 we got our first hi-def video server. Unfortunately, with the still-emerging technology came crashes during the shows, which wasn't fun for the audience, or for us on stage! We had literally become slaves to the machine, and there was a period where we were always in fear of the next inevitable crash. As server technology improved, we upgraded, upgraded again, and yet again recently with a pair of Mac Pros that guaranteed consistent, trouble free shows. Somewhere in the middle of all that, I also simplified my rig with an all-in-one sample playback pad, opting to let the server do its job. I could finally relax and play with confidence, and my job continues to be a genuine pleasure.

As a 12-year-old dreaming how cool it would be to play drums for a living, I could never have imagined the road that lay ahead. During my evolution with Al, I went from pounding on his accordion case with my fists, to essentially being the air traffic controller of a world-class show. He even coerced me to sing, although nobody could accuse me of being a singer! And with 14 studio albums (most of them Gold and Platinum,) world tours, Grammies, and TV & videos to my credit with Al, I've certainly come a long way professionally and personally in those 35 years (and counting.) I'm enjoying a successful career by any standard, and am proud to be considered a modern drummer.

Through it all, I never lost that soft spot for the old songs, classic drum sounds, and simpler approach to drumming. So, between tours, I continue to play with a few Los Angeles bands on the local scene - no tracks, no costumes, no in-ears, not even monitors. I still get to be that not so modern drummer.